Letters from Lodi

An insightful and objective look at viticulture and winemaking from the Lodi

Appellation and the growers and vintners behind these crafts. Told from the

perspective of multi-award winning wine journalist, Randy Caparoso.

Liberating Americans from the yoke of conventional wine preferences

j

Summer wine lovers in Lodi's Guantonios Wood Fired, a farm-to-table restaurant known for its selection of alternative (i.e., unconventional) style wines.

Early history of American wine appreciation

Those who don't learn from history are doomed to repeat it. Usually, of course, when we cite this well known quote, it is in reference to more sinister subjects.

When it comes to wine, though, it also seems like we are constantly repeating the past, and only punishing ourselves for it.

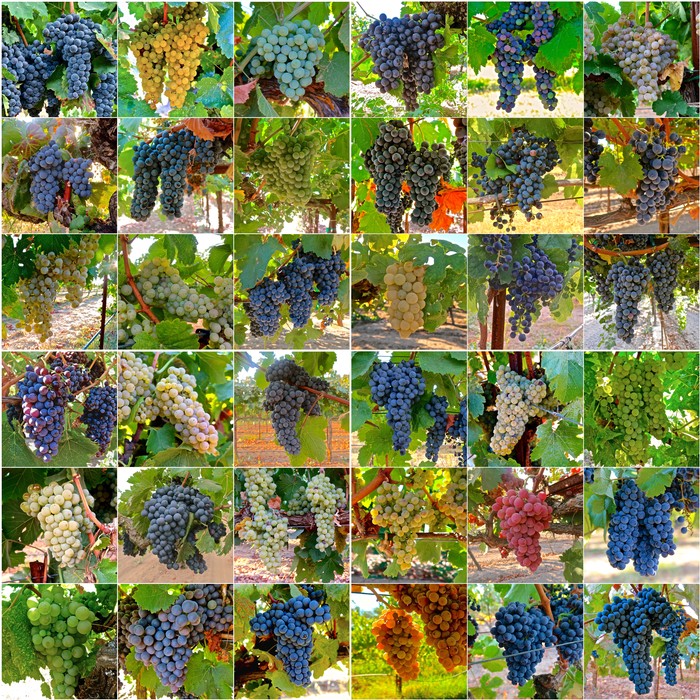

Take, for instance, our nasty habit of simplifying what makes wine interesting. As Americans, we've been doing that since the 1800s, ever since the country's earliest wine entrepreneurs, particularly in California, began planting every grape they could get their hands on, in every possible corner of the state. They did that, of course, because they had no idea what grapes grow best in the New World, nor exactly where to put them.

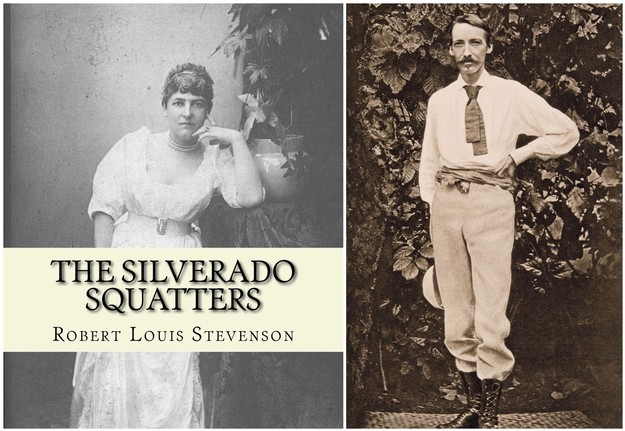

Quote from Robert Louis Stevenson's 1880 tome, The Silverado Squatters: "“Wine in California is still in the experimental stage; and when you taste a vintage, grave economical questions are involved. The beginning of vine-planting is like the beginning of mining for the precious metals: the wine-grower also “Prospects.” One corner of land after another is tried with one kind of grape after another. This is a failure; that is better; a third best. So, bit by bit, they grope about for their Clos Vougeot and Lafite..."

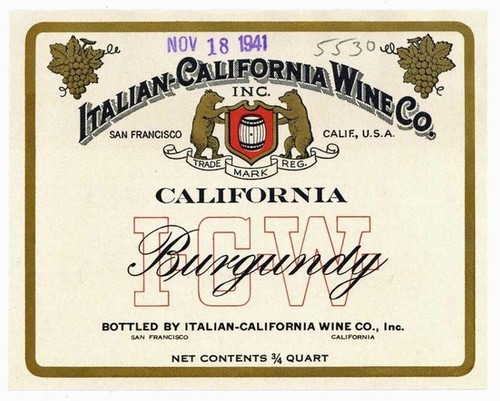

Once they got started, they soon discovered that it was grapes such as Zinfandel and Colombard (originally called West's White Prolific) that seemed to grow best. Then they proceeded to sell wines made from said grapes. The easiest way was to package them under the names most Americans of European ancestry understood: By giving them European place names (i.e., semi-generic) such as Burgundy, Chablis, Moselle, Sherry, Madeira, Port, and so forth.

Because, in the late 1800s and early 1900s, Californians cultivated dozens of different grapes, early American bottlings were typically made from any or, often enough, all of of the grapes that were grown—with absolutely no restrictions as to what grapes could go into any wine.

Early 1940s label for the Italian Swiss Colony brand of Burgundy.

Never mind the fact that red Burgundy in France is actually made from Pinot noir, France's Chablis is made exclusively from Chardonnay, or that white wines from the Moselle are made from Riesling—things that are regulated by law in the countries of these grapes' origin.

In fact, since the earliest experimental plantings of grapes such as Pinot noir and Chardonnay in California did so poorly, virtually no California Burgundy or Chablis were made from the grapes originally associated with those place names. Not one drop. Instead, they were made from grapes such as Zinfandel and Colombard, eminently suited to California's Mediterranean climate. This was the way the American wine industry did business all the way up until the 1960s; and to a certain extent, still does.

What's wrong with this? Nothing. We are Americans, after all. No one should be able to tell us how we produce, sell or appreciate wines in our own country.

Just four dozen of the over 130 different wine grapes commercially grown in the Lodi appellation.

What might be considered "wrong," though, is the consequences of how the American wine industry has since evolved, not all of which makes sense. Because we simplify, say, notions of quality, we create an entire system of winegrowing, production, sales, marketing and media conversation that narrows down the perception of quality to a few basic standards. Very few grape varieties of significance, very few ways of making wine, thereby limiting variety of wines, choices, tastes.

The number of different wines should be as vast and varied as the number of grapes commercially grown in the world (there are hundreds), all the world's regions and vineyards (thousands), and all the individuals cultivating and crafting wines (countless). Why would we want to limit ourselves? While the industry does its best to dictate conformity and uniformity, consumers should resist. So let's talk more about how this came about, at least in the United States.

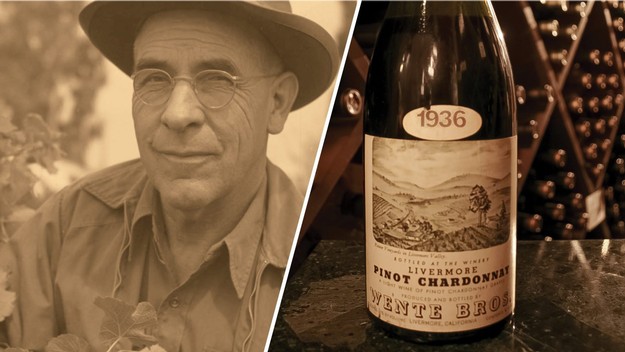

Second generation 1930s wine industry pioneer Ernest Wente and one of America's first bottlings of varietal wine, the 1936 Wente Brothers Pinot Chardonnay. Wente Vineyrds.

Progression from generic to varietal wines

Invariably American viticulture improved to the point where, in the post-Prohibition years⏤starting in the 1930s and lasting all the way up until the 1970s⏤more and more Americans began to appreciate table wines made from grapes known to produce many of the finest wines of Europe. Especially cultivars that are now very familiar to the average consumer, such as Pinot noir, Chardonnay, Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Sauvignon blanc, and a dozen or so others. Use of these grapes made perfect sense: The better the grapes, the better the wine.

Bottlings made primarily from these key grapes became known as varietal wines⏤"varietal" being a made-up designation, nonetheless quickly attaining legal standing. Following Prohibition (ending in 1933), the feds stepped in and passed legislation requiring that wines sold by the names of grapes contain at least "51% juice from that grape variety."

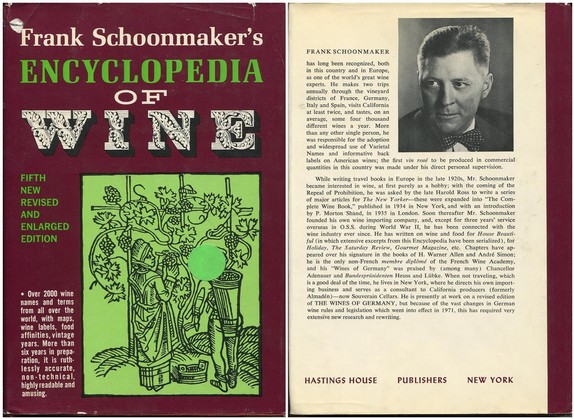

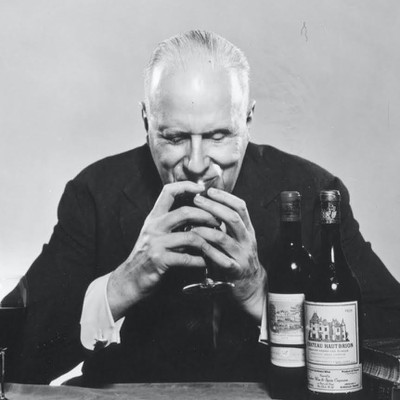

Slowly but surely Americans began to wise up, at least aspirationally, recognizing the intrinsic "nobility" of certain grapes, even if planted in America's unproven sites. By 1964, the widely read wine writer Frank Schoonmaker was writing in his landmark Franck Schoonmaker's Encyclopedia of Wine: "A noble variety is one capable of giving outstanding wine under proper conditions, and better-than-average wine wherever planted within reason... A noble wine is one that will be recognized as remarkable, even by a novice."

All the same, generic-labeled wines such as Burgundy or Chablis, usually sold by the gallon or half-gallon jug, dominated table wine sales in the U.S. all the way up until the end of the 1960s, although it was varietal wines that eventually became associated with premium quality.

The 1960s push for higher varietal percentages

In his 1976 book called Gorman on California Premium Wines, Robert Gorman cited Beaulieu Vineyard, Charles Krug Winery, Louis M. Martini, Inglenook Vineyards, Wente Brothers, Stony Hill, Buena Vista and Martin Ray as being among top brands leading the California wine industry with premium varietal bottlings of significance.

Wrote Gorman, "By the late 1960s, those winemakers who had laid an early foundation for premium wines were producing very high quality wines... Both the success of these pioneers and the new interest in premium European wines had a profound effect. Within a decade, the California wine scene has virtually been turned upside-down."

There was, however, a growing consensus at the time that the federal law allowing varietal labeling with a minimum of 51% of a stated grape going into wines was simply not enough. In his October 1969 article entitled "Is There Great Wine In California?" published in Esquire magazine, the noted (at the time) wine critic and bon vivant Roy Andries de Groot echoed the growing frustration with the old law:

Wherever I went [describing a recent tour of top California vineyards], I heard the fine producers describe the present law as "grossly misleading," "dishonest," "absolutely ridiculous." They feel the law must be amended...

Widely read culinary and wine author (between the 1950s and 1970s) Roy Andries de Groot.

In every country the first wines are those with the strongly individual character of a particular type of grape. Bordeaux is dominated by Cabernet Sauvignon, Burgundy by Pinot noir. If you buy a French Chablis or Montrachet, the French government stands behind the label, to guarantee that the wine is made 100% from the Pinot Chardonnay [the former name for Chardonnay] grape. There is a specific legal definition of every wine village in France. This is known as the "controlled appellation" law.

The U.S. has the weakest such law of any wine-producing country. If you buy a California bottle labeled "Pinot Chardonnay" the law requires that only 51% of the wine in that bottle need to be from the Pinot Chardonnay grape. The remaining 49% can be cheaper juice from any lesser grape. The unfair competition against the fine producer is obvious. He makes his wine 100% from the noble and expensive grape, and therefore has to charge, perhaps, $4 or $5 a bottle. His competition, taking full advantage of the 51% law, is still allowed to mark his label Pinot Chardonnay, but can sell his bottle for around $2.25. Yet one only has to taste the two wines side by side to realize the 100% single-grape is as a prince to the 51% pauper!"

Finally bowing to this growing sentiment, in 1978 the BATF (Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms, which took over regulation of alcoholic beverages in 1972) finally did pass an amendment raising the minimum for varietal wine labeling to 75%. This ruling, going into effect on January 1, 1983, still stands stands to this day.

California Chardonnay pioneers Eleanor and Fred McCrea of Stony Hill (founded in 1951), whom Roy Andries de Groot proclaimed in 1969 to be among America's few "great" handcraft estates, while producing (at the time) less than a 1,000 cases a year.

The varietal tyranny of the 1980s

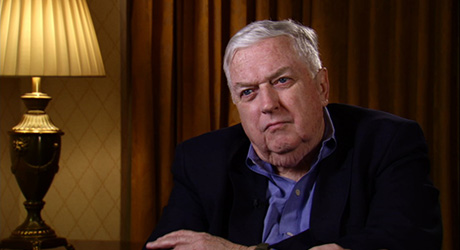

While appreciation of varietal wines were indicative of the growing sophistication of American consumers, it soon became something of a tyrannical yoke which, to a large extent, still stunts the evolution of the American wine industry today. In September 1981, The New York Times wine columnist Frank Prial penned perhaps the most cutting critique of this evolving distortion of wine quality in an article entitled "A dissenter's view of California wines."

While California varietals had laudably improved by the early 1980s, Prial mercilessly mocked what he called an emerging "cultism" of brands and slavish obsession over varietal intensity bordering, from Prial's perspective, on obsequiousness. Like "wearing clothes with someone's name on it."

Prial wasn't specific about exactly what is wrong with this (then) new fangled enthusiasm. All he could say was that it is unseemly. Seeing that this is still exactly how most American wine is appreciated to this day, Prial's indictments are as applicable today as it was over 40 years ago.

Longtime The New York Times and nationally syndicated wine columnist Frank Prial.

At the end of his diatribe, Prial suggested that there may come a day when many wine lovers will simply "walk away" from this state of affairs. The recent rejection of many of the conventions of wine industry⏤coupled with a growing embrace of more "natural" style wines⏤by today's latest generations may be indications that Prial's predicted conjecture may finally be coming to pass. In his words:

I used to be among those who were constantly trying to write something perceptive and flattering about California wines. ''The California miracle... 30 years ago an industry in ruins... up from the ashes of Prohibition... new wineries every week... better and better... more and more''⏤ not original, but heartfelt.

Not surprisingly, a couple of years in Europe, away from that charged atmosphere, effects a few changes. Actually it started fairly early in my tour. Lonely travelers would appear bearing California wines in their kits. They⏤the wines, not the travelers⏤seemed to have lost some of their charm, the reds in particular. Was it some kind of latent snobbism? Was it possible to become the Henry James of wine, eager to embrace the Old World and shuck off the New?

Then there were a couple of trips home and the concomitant access to plenty of California wine. Same results. I found myself asking, reluctantly, what all the fuss was about? The wines were good, some of them, and often delightful to drink. But the unremitting enthusiasm of their fans and promoters, the breathlessness, seemed excessive. The miracle seemed a bit more commonplace; it appeared that, having expressed our amazement that the dog could talk, it was time to determine what it might have to say...

While not specifically mentioned in his 1981 indictment of California wine, the Chateau Montelena Chardonnays of the '70s and '80s was representative of the elitism perceived by Prial, particularly in terms of its presumed triumph over "imagined enemies" (i.e., comparable wines of France). prnewswire.com.

In America wine has its own newsletters, its own stars, its own clubs, even its own vocabulary. Where else in the world would someone sip a little wine and then, with a straight face, remark, "I understand they brought these grapes in at 24 Brix."

What is or are "Brix"? Sorry, you are not a member. Cultists flourish not so much on shared joys as on imagined enemies. American wine enthusiasts dearly love the image of the French expert, white-faced and with fists clenched because he has just identified a California Cabernet as a Chateau Mouton-Rothschild 1945...

Recently a reformed newspaperman turned California wine fan appeared in Paris. Here is one of the stories he told: It seems that there is a small winery "up in the valley" whose output is highly prized by the cognoscenti, so much so that the wine maker-proprietor can sell everything he makes with his mailing list. My friend was ecstatic because he had been able to take over a place on the list from a friend who preferred drugs.

This particular winery does produce good wines, but not all are worth getting in line for. The notion that one winery will turn out consistently superior wines, year in year out, the way Cartier does watches, is absurd. This is not wine drinking; it is a kind of bush league elitism, like clothes with someone else's name on them.

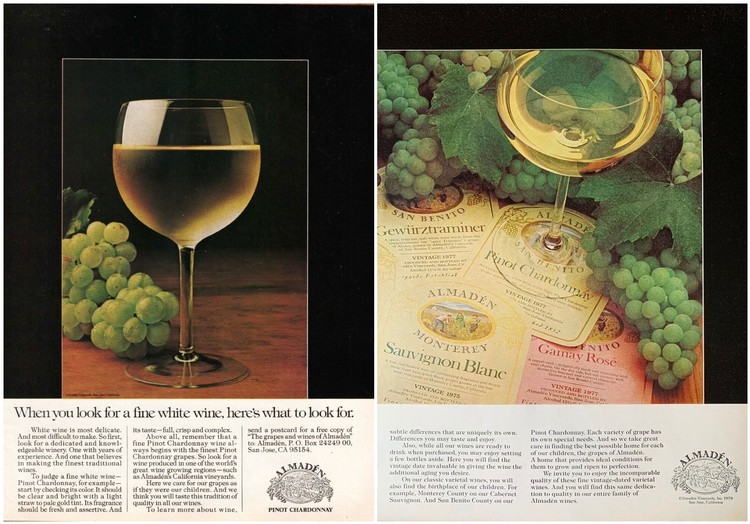

A pair of 1979 ads for the Almadén brand, diving deep into why varietals are the finest wines of the day.

Not that elitism is confined to the customers. An astute Frenchwoman with years in the wine trade said recently: "I adore the California Chardonnays, but I don't know what to do with them. They certainly don't go with meals." She was half right. They are meant to go with meals, but many of them do not. Like overbred dogs, they have gone beyond their original purpose. They are too aggressive, too alcoholic. They are showoff wines made by vintners who seem to be saying, "I can outchardonnay any kid on this block"...

The point is this: The drinking of wine in America, particularly American wine, is on the brink of becoming inbred and precious... One day the rest of the country, bemused and probably irritated by all this, might just shrug and walk away. Thousands of people wake up every day, smile and say: "I don't have to play tennis any more or listen to people who do." One day the same people might wake up and say: "I don't have to drink wine either, or listen to⏤or read⏤people who do."

The absurdity of varietal standards

The phrase "varietal character" has been used to describe sensory qualities associated with a particular grape identified on the label of a bottling at least since the 1960s, picking up steam during the '80s. The varietal character of a Cabernet Sauvignon, for instance, is usually that of a red wine that exudes aromas of blackcurrant, dark berries, some degree of herbaceousness, with a full body, generous tannin and lots and lots of oak flavor. The varietal expectation of a Zinfandel is that of a very berry-like red wine, medium to full in body/tannin, and zesty in flavor sweetened by perceptible oak.

Lodi's current top six wine grapes are a reflection of the American wine industry's most recent push of just a few varietal wines.

Varietal character, in this sense, has become the primary way in which American wines are appreciated, evaluated, and sold. The more a wine tastes like, say, a "Cabernet Sauvignon," "Zinfandel" or "Chardonnay," the better it is considered to be.

Towards that end, Americans have even devised their own numerical system of rating wines, popular ever since the 1980s when, as Prial pointed out, critics and consumers began to favor wines that can "outchardonnay any kid on this block."

The sad part of passing judgement on wines in this fashion is the most fundamental aspect of wine itself: The fact that wines are made from grapes, and grapes simply don't grow in exactly the same way in different vineyards, different regions, and especially in different countries. Even novice wine lovers understand this, even if the domestic wine industry refuses to give it to them.

A Chardonnay grown in Sonoma Coast, for instance, is almost always rounder and more opulent in flavor than Chardonnays grown in Santa Barbara, in Oregon, or Burgundy in France. Within just the Burgundy region, wine lovers have long known that Chardonnays grown in Chablis are more tart, lighter, leaner and more minerally tasting than Chardonnays grown in Meursault or Puligny-Montrachet. You couldn't make a wine grown in Chablis taste like a Meursault or Puligny-Montrachet even if you tried, and vice versa. Thus, to expect a Chardonnay grown in Oregon to be as full and opulent as a Sonoma Coast Chardonnay, or to even come close to resembling a white Burgundy, is⏤there is no other way to put it⏤completely daft.

The biggest problem with comparing "Chardonnays" from different region: Drastically different terroirs—in this comparison, Mokelumne River-Lodi (top), Russian River Valley-Sonoma Coast (middle), and France's famous Puligny-Montrachet (bottom)—making production of wines of varietal uniformity an impossibility.

Yet thanks to industry pressure to standardize sensory qualities, most Americans still expect a sense of sameness in wines made in different places. A few years ago a UC Davis professor even wrote an entire book based on the premise that terroir—the time honored concept of "sense of place" considered self-evident by Europeans—does not really exist, except as an instrument of elitists.

Expecting wines grown in different places, even when made from the exact same grapes, to meet the exact same standards of intensity, let alone nuances of sensory qualities, would be like expecting Taylor Swift to sing "Wide Open Spaces" the exact same way as the Dixie Chicks, or Matchbox Twenty to cover "Time After Time" the same way as Cindi Lauper. Not going to happen, and why would anyone want that?

Yet this is how much of the wine industry expects wines (at least American wines) to be made⏤by meeting the exact same varietal standards. It doesn't help that so-called critics and experts constantly pound that into consumers' heads by insisting on rating varietals with the use of 100-point scores; as if all wines, no matter where they're grown, should meet the same sensory qualities. No wonder Prial was tearing his hair out back in 1981.

It makes you think: Maybe Americans got things more correct 100 years ago, when they were buying wines by place names. It was wrong, of course, to use European place names for wines grown in America, but at least that practice acknowledged the basic significance of provenance. In Europe, after all, they still buy most wines that way. That is to say, wines are still identified primarily by where they come from, not by the grapes from which they are made.

Wine Folly's basic visual description of "natural" wines, a movement reflecting some of the most recent changes in consumer preferences towards more variation (rather than sameness) of tastes and quality expectations. media.winefolly.com.

Is it possible to appreciate American wines for what they are, not what they're supposed to be?

Why should Americans move away from varietal standardization? Because we are now a lot better than that. Grape growers are better than ever, and our finest winemakers have become proficient practically to the point of wizardry. They all deserve a lot better than to end up having their products judged in ways that presume all wines should taste alike, no matter where they're grown.

Appreciation of wines primarily in terms of origin rather than varietal identity means appreciating a Napa Valley wine for tasting like it comes from Napa Valley. A Paso Robles, a Lake County or a Lodi wine for tasting like they come from Paso Robles, Lake County or Lodi, and not from Napa Valley, or South Africa, Australia, France, Italy, or anywhere else in the world.

Are consumers ready for this? I'd contend that they always were. The very fact that many American wine lovers can easily understand and appreciate classic European wines is absolute proof of that. There is no reason not to think even the average consumer can't make the mental jump from European to American wines when judging wine quality.

If anything, it is probably a bigger challenge for the American wine industry. A matter of the industry itself coming to the same logical conclusions made long ago by much older wine producing countries. To quit making wines as if they all come from the same place and should be made to taste exactly the same. Encouraging consumers to appreciate wines for what they truly are: Products of place and, in that sense, Mother Nature herself, in all her unpredictable glory.

And stop repeating the same old mistakes!

The unconventional selection of wines at Lodi's Guantonios Wood Fired restaurant.