Letters from Lodi

An insightful and objective look at viticulture and winemaking from the Lodi

Appellation and the growers and vintners behind these crafts. Told from the

perspective of multi-award winning wine journalist, Randy Caparoso.

Piquepoul, Grüner Veltliner, Cinsaut, Blaufränkisch—four contemporary varieties foreshadowing the future of California wine

Early morning Picpoul Blanc harvest, Acquiesce Vineyards, Mokelumne River-Lodi appellation.

How is your contemporary wine grape IQ? Are you up on the latest "alternative" varietals? Should you even care?

If a grape makes perfectly delicious wine, I would say "yes" to the last question. The way I see it: There are many grape varieties—hundreds of them, probably, grown all over the world—that may be new, unknown, exotic or even strange to most of us here in America. Yet in the parts of the world where these grapes come from, they are practically pedestrian, making perfectly familiar drinking wine.

What may be strange here is usually an everyday thing elsewhere. Or vice versa. Take, in a reverse-case scenario, a grape everyone knows here in California: Zinfandel, which (despite the commercial dominance of grapes such as Cabernet Sauvignon and Chardonnay) is still the most widely planted grape in Lodi. Zinfandel, however, is not grown in Spain, France or Germany, three of the largest wine countries in Europe. And why should Spain, France or Germany care about Zinfandel? They have plenty of grapes of their own to make wine from.

Crljenak Kaštelanski grapevine—a genetic precursor to California's Zinfandel—in Croatia. A. Matulić, Wikimedia Commons.

Because the wine world has been shrinking, though, there are smatterings of Zinfandel grown in other countries such as Australia and South Africa. Still, in those places, the grape is still considered an esoteric varietal—interesting yet "weird," only for the few curious consumers.

Zinfandel is grown in Southern Italy, but there it is known as Primitivo and considered a wine grape of somewhat secondary, or lower class, status. In recent decades it was discovered that Zinfandel actually originated across the Adriatic Sea from Italy in Croatia, but there it is called Tribidrag or Crljenak Kaštelanski. Point being, what is "normal" here can be considered strange or exotic elsewhere, even in places where a grape was first grown.

Between the 1850s and 1880s, when grapevine entrepreneurs in California first started bringing in as many European grape varieties as they could find, they ushered in an era in which an impressive variety of wine grapes were soon cultivated, all the way up until the 1960s.

In the 1929 industry book entitled Black Juice Grape Varieties In California, for instance, the California Department of Agriculture catalogued and provided precise descriptions of a host of varieties commercially grown at that time (even during Prohibition). Listed among "White Juice Grapes" (i.e., for white wine production) were varieties that are now obscure in California, such as Burger (a.k.a., Mondabon), Chasselas, Feher Szagos and Folle blanche (a.k.a., Gutedel). Today, most wine industry professionals would recognize Colombard, Riesling and Sauvignon (better known as Sauvignon blanc) on the 1929 list, but there was no Chardonnay, Chenin blanc, Grenache blanc, Grüner Veltliner, Pinot gris (a.k.a., Pinot grigio), Piquepoul (a.k.a., Picpoul blanc) Roussanne or Viognier—the latter group, now among the more popular (or at least recognizable) varietal whites of the past 40 or so years.

The gap between the early 1900s and early 2000s among "Black Juice Grapes" (i.e., for red wine production) on the 1929 Department of Agriculture list is just as big or bigger: You see varieties that are pretty much long defunct in the California industry such as Alicante Ganzin, Aramon, Béclan, Black Prince (a.k.a., Rose of Peru), Blue Elba, Calmette (a.k.a., Grand noir de la Calmette), Freisa, Grignolino, Gros Colman, Jacquez (a.k.a., Black Spanish), Lenoir, Portuguese Blue (a.k.a., Blauer Portugieser), Ribier (a.k.a., Brun Fourca), Salvador, Sérine (a.ka., Persan), and Sainte-Macaire; while among the grapes known in 1929 and still familiar to us today are Alicante Bouschet, Barbera, Cabernet Sauvignon, Carignan, Grenache, Malbec, Nebbiolo, Syrah and Zinfandel.

Other red wine grapes we know today are listed under synonyms such as Black Pinot (a.k.a., Pinot noir), Crabb's Black Burgundy (a.k.a., Mondeuse noire), Mataró (a.k.a., Mourvèdre or Monastrell), Malvoisie (Cinsaut), and Valdepeñas (Tempranillo). In the history of the California wine industry, there were always grapes identified in error, such as Gamay (now known to be Valdiguié), Mourastel (most likely Graciano), and of course, most famously, "Petite Sirah" (once mistakenly thought to be a variant of Syrah, but is actually a crossing of Syrah x Peloursin correctly called Durif). Some black skinned grapes important today but missing on the 1929 list include Merlot, Petit Verdot, Pinotage, Sangiovese and Tourgia Nacional, which are among the over 100 varietal reds produced in Lodi today (see our 2024 post, Latest update on the 100+ grapes grown in Lodi).

If anything, by the "modern era"—which many would say started in the 1960s/'70s—the number of wine grapes considered commercially feasible began to shrink rather than expand. At that time, when the market began shifting from sweet fortified wines and generic jug wines to varietal wines, the California wine industry collectively decided that consumers were better off exposed to just a few of the world's "major" grapes, worthy of varietal bottlings. You know the names: Cabernet Sauvignon, Chardonnay, Sauvignon blanc (a.k.a. Fumé blanc), Pinot noir, Merlot, Chenin blanc, Riesling, Petite Sirah, and maybe about a dozen more.

Black, Asian and Anglo grape pickers in the 1890s. San Joaquin County Historical Society Museum.

Times change, same as it ever has. After a while, both consumers and industry professionals begin to get bored of present-day status quo. They look for alternative style wines, made from other grapes. More importantly, at least here on the West Coast, they realize that the world does not revolve around just Cabernet Sauvignon, Chardonnay, Sauvignon blanc or Pinot noir. That other grapes make perfectly fine and compelling wine, which consumers become more and more aware of.

It is not just the conception of "varietal" viability that is resulting in current changes in industry interest and consumer perceptions. It is also the fact that vineyard and winemaking technology has improved so much, high quality wines are now being produced in a wide range of regions, each with distinctive terroirs (i.e., "sense of place") of their own. Expansion of wine types is inevitable with expansion of wine regions.

For example, since the 1970s it has been well known that grapes such as Cabernet Sauvignon, Sauvignon blanc, Merlot and Chardonnay ripen very well in regions such as Napa Valley and in the inner coastal areas of Sonoma County. Pinot noir, on the other hand, was long thought to be far less suitable to California. It existed in California vineyards prior to the 1960s, but usually made thin, meager wines.

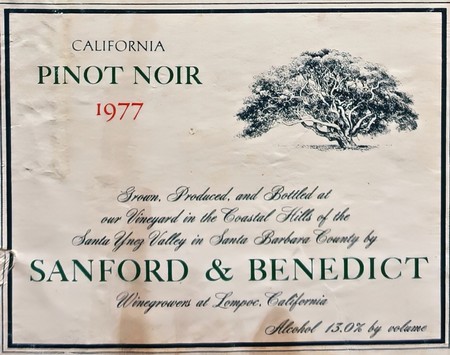

Label of historic 1977 bottling of Santa Barbara Pinot Noir by Sanford & Benedict, grown in a region once considered a remote California outpost.

It wasn't until the 1980s and '90s that it was "discovered" that Pinot noir, in fact, makes fabulous wines if grown in parts of the state that were once considered too cold to even ripen grapes. It was vineyard technology that changed that equation; and now, Pinot noir is among California's most widely planted grapes, thanks to all the newer vineyards that have gone into places once considered viticultural outposts, such as Santa Barbara, West Sonoma Coast, the "Deep End" of Mendocino's Anderson Valley, and other suitably cooler climate spots.

The expansion of industry interests and consumer tastes, in other words, is not just a byproduct of market decision-making. It is also a direct consequence of improved science, technology, skill and savvy investment allowing the industry to plant in new regions. When better or different wine can be made, consumers respond by drinking more of it.

The big difference between what occurred during the late 1800s when vintners were throwing as many different grapes as possible up against a wall to see what sticks and what has been happening just over the past 30, 40 years is that growers and vintners have quite a bit more information at their disposal, and the benefit of more hindsight in terms of understanding marketing trends.

Lodi Winegrape Commission's Dr. Stephanie Bolton with typically generous, plump berried cluster of Cinsaut, a classic Mediterranean grape eminently suited to Lodi terroir.

In a warm Mediterranean climate region such as Lodi, for instance, important planting decisions are now based less on wishful thinking than on knowledge of what grows best in the region. Cultivars of Mediterranean origin are no-brainers because these are grapes that come with a built-in ability to adapt to places such as Lodi, a quintessential warm climate region.

Perhaps the most dramatic example of this ongoing phenomenon is Cinsaut, which is planted all over Southern France along the Mediterranean Sea. There is a reason why Lodi's oldest vineyard—the highly acclaimed Bechthold Vineyard, originally planted in 1886—consists entirely of Cinsaut. The sheer age of these vines is a testimony to how suitable the grape is to the terroir. Ideal environment + healthy grapevines = long, productive life. Therefore, it stands to reason that brand new vineyards planted to well adapted grapes such as Cinsaut should do very well in Lodi, which that is exactly what is happening as we speak.

Here's the thing: Lodi grown Cinsaut would never have become respectable if both vintners and consumers hadn't changed as well. Cinsaut, as a matter of fact, makes red wines with sensory qualities that are pretty much the opposite of Cabernet Sauvignon's—soft, easy, fruit driven. Yet this is a fruit profile that consistently expresses a distinctive spice and natural acid balance that Cabernet Sauvignon, for the most part, lacks (most Napa Valley Cabernet Sauvignons, for instance, require acid "adjustments" to bring the wines into balance).

Bechthold Vineyard, Lodi's oldest surviving vineyard (planted in 1886), consisting of 25 acres of own-rooted Cinsaut.

Once vintners recognized Cinsaut's intrinsic qualities as unique unto themselves, and consumers began to respond with increased appreciation for softer, lighter, spicier red wines, then voilà, consumer searches for Cinsaut picked up steam—really, only during the past 10, 15 years, despite the fact that the grape has been grown in the region for well over 100 years (although, up until the early 2000s, Cinsaut was known primarily as "Malvoisie" or "Black Malvoisie" in California).

And this is what might make a grape "contemporary." We are talking about varieties that, up until 10 or 20 years ago, were relatively unknown to most American consumers; and for the most part, familiar only in their countries or regions of origin.

But these are the grapes that are becoming more important because 1) they grow extremely well in climate zones such as Lodi's, and 2) they make terrific wines. Let us dive deeper into four of these varieties, and why their importance to the entire American wine industry may (even if maybe not) only increase over the next few years or decades.

Piquepoul grapes close to harvest in Lodi's Acquiesce Vineyards.

Picpoul Blanc (a.k.a., Piquepoul)

Why is the Piquepoul grape—normally bottled as Picpoul Blanc—important? Mostly because it produces a white wine that meets a trending consumer taste: Very light (typically, alcohol levels barely reaching 12% ABV), outwardly tart, with as much or more mineral character than outright fruitiness. Something of an "unChard."

The other factor is climatic: Piquepoul thrives under warm to hot conditions, such what you find in Lodi's Mediterranean climate zone—or in the grape's native region in South-West France's Picpoul de Pinet appellation—while retaining all the acidity in the world. Hence, the name of the grape itself, which in French translates as "lip stinger." A lip smacking tartness is the grape's signature taste.

In today's rising global temperatures, Piquepoul's importance looms larger than ever before. Thirty or forty years ago practically no American had ever heard of the Piquepoul grape, unless they happened to have passed through Picpoul de Pinet (an appellation clinging to the seaside town of Perpignan) on the Mediterranean coast, on the way to Spain from Montpellier or Marseille. This is changing.

Mokelumne River-Lodi AVA Piquepoul harvest.

And it may change even faster if some of today's more respected climatologist's prediction come true: That cooler climate regions, such as West Sonoma Coast or Santa Barbara in California, and Willamette Valley in Oregon, will soon average the same amount of growing season heat units (i.e., GDD, or growing degree-day) as what is currently found in regions such as Lodi in California, Provence in France, much of Spain, Sicily, Greece or North Africa (see a detailed report in our 2024 post, How global warming is changing winegrowing in Lodi and the rest of the world).

Piquepoul is a grape you will need to know, willingly or unwillingly.

Lodi growers have been cognizant of the industry's soon-to-be pressing needs. There are currently just over 21 acres of Piquepoul grown in the appellation that we know of, split among half-a-dozen growers. 21+ acres may not seem like a lot, but keep in mind that's more than all the acres of Chardonnay existing in California up until the 1940s.

The producer of longest standing in Lodi is Acquiesce Winery & Vineyards, which has been growing the grape since 2009. Over the years we have presented Acquiesce's Mokelumne River-Lodi AVA Picpoul Blanc to sommeliers and other wine professionals in blind tastings next to bottlings of Picpoul de Pinet from France. Quite frankly, most of them can't tell the difference; mostly because, without a doubt, Piquepoul produces a light, ultra-dry, neutral tasting wine in both Lodi and France; and ultra-dry, neutral tasting wine is exactly what lovers of Picpoul Blanc like. Besides a table wine, Acquiesce now produces a champagne method Sparkling Picpoul Blanc, which is extraordinarily fine and delicate—as wonderful a "champagne" grape as any!

Perpignan, a Mediterranean seaside town renowned for hundreds of oyster beds, located alongside the Picpoul de Pinet appellation, where a reportedly 1,400 hectares (3,000 acres) of Piquepoul are cultivated.

There is another California brand called Lorenza Wine that produces a Lodi grown Picpoul Blanc (farmed by Bokisch Vineyards) that tastes more like French Picpoul de Pinet than most Picpoul de Pinets. It is a wine that makes you crave a tray of raw oysters; the tart taste of the Piquepoul grape serving as all the "lemon," or mignonette (red wine vinegar with shallots), you need. And like Acquiesce, Lorenza bottles a fresh and lively Sparkling Picpoul Blanc.

That is the cool thing about the grape and the modestly growing number of Picpoul Blanc aficionados. If they wanted fruity, they'd be drinking Chardonnay. If they wanted more flowery wine, they'd be drinking Viognier. If they wanted more tropical fruit or herbiness, they'd go for Sauvignon Blanc. Instead, they want Picpoul Blanc. It is a varietal doesn't need to be "as good as" other varietals, and just might help save the California wine industry from the future climatic onslaughts of Mother Nature.

Grüner Veltliner clusters in Lodi's Mokelumne Glen Vineyard.

Grüner Veltliner

Many wine buffs might be surprised that Grűner Veltliner is even cultivated in a Mediterranean climate region such as Lodi. Especially since the grape is associated with the largely Alpine regions of Austria, where it is that country's most widely planted grape,

Grüner Veltliner does grow, however, in a fairly varied (for Austria) range of climate zones: The coldest regions producing the highest acid, mineral inflected, citrusy tart and peppery spiced styles, and the warmest regions producing more gentle, rounder whites that can be quite high in alcohol (topping 14% ABV) with ripe, occasionally off-dry fruit profiles veering into the Hawaiian-like pineapple spectrum.

In what sensory realms have the first few bottlings of Lodi grown Grüner Veltliners fallen? Believe it or not, somewhere in between the Austrian typicities: Light alcohol (11.5% to 12.5% ABV), tart acidity, more grapefruit/citrus than ripe pineapple (as strange as it might seem that Austrian iterations should be "fruitier" than those of Lodi), and slivers of minerality; although (so far) pretty much lacking the spice found in the finest Austrian bottlings.

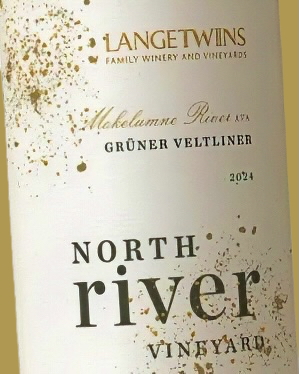

The vineyard-designated label of the newly released Grüner Veltliner farmed and produced by LangeTwins Family Winery & Vineyards.

Be that as it may, the cultivar is still too sparsely planted for us to make a blanket statement, "This is what Lodi style Grüner Veltliner tastes like." A lot of this reflects the relative newness of Lodi's plantings: LangeTwins Family farming (for vineyard owner Nick Jones) the biggest and newest parcel (just over 4.5 acres), and Mokelumne Glen Vineyard's parcel (barely a half-acre) just now approaching a tenth leaf.

Both the LangeTwins Family and Mokelumne Glen sites are located near the banks of the Mokelumne River (falling within the boundaries of Lodi's Mokelumne River AVA) which, according to LangeTwins Family vineyard manager Aaron Lange, has helped the grapevines manage themselves through the seasonal challenges such as predictable heat spells.

Good enough, in fact, for a LangeTwins Family farmed bottling—a 2023 produced by Markus Wine Co.—to have been ranked #24 in one major wine critic's list of "Top 50 Wines of 2024," while garnering this concise description: "Brightness, austere, lifted aromatics of white peaches."

Mokelumne Glen Vineyard Grüner Veltliner harvest.

Just last month LangeTwins Family released their own, pure stainless steel finished 2024 North River Vineyard-designated Grüner Veltliner, which is even edgier in natural acidity than the Markus Wine Co. bottling, and has all the citrus and crunchy/tart pear/apple qualities associated with the varietal. In the opinion of LangeTwins Family Director of Winemaking Susana Vasquez, "Lodi's warmer climate only seems to enhance the varietal's signature freshness while retaining a saline minerality... alongside classic Grüner notes of lime zest, fresh herbs, yellow peach and citrus blossom."

Then, notably, there is the soon-to-be released 2024 Mokelumne Glen Vineyard grown Grüner Veltliner crafted by Lodi's Christopher Cellars which positively exudes lemon/grapefruit/orange zest acidity and perfumes. In fact, it is just as silky yet zestier than most comparable bottlings imported from Austria, despite four months spent in neutral French oak to help tame a ferocious level of natural acidity.

Clearly, no one should sleep on Lodi, which is smashing the assumptions that fresh, delicate, acid driven white wines cannot be produced in warm climates to smithereens.

Lightly pigmented yet typically brilliant color of Lodi grown Cinsaut in glasses.

Cinsaut (a.k.a. Cinsault)

Let's talk about Cinsaut more in terms of its sensory profile than its Mediterranean identity. A grape can become popular because it grows very well in a place, thus producing excellent wine. But from a commercial standpoint, a grape becomes popular mostly because it makes a wine that tastes good.

Not too long ago, most Americans tended to judge the quality of red wines in terms of sheer intensity: Intensity of color, intensity of body, of tannin, of oakiness, and everything in between. The "bigger" the better. Hence, the popularity of Cabernet Sauvignon, now considered the finest of varietal reds, especially in California.

The popularity of Pinot Noir—always a softer, silkier, lighter colored and more fragrant style of red wine than Cabernet Sauvignon—changed that paradigm somewhat, starting in the 1980s and '90s. As repugnant as he was, the character "Miles" in the movie Sideways also helped to popularize the varietal category.

Ancient vine Cinsaut harvest in Mokelumne River-Lodi's Bechthold Vineyard.

Cinsaut might be something of a Pinot Noir 2.0; not because it is nearly as grand or elegant as the finest of Pinot Noirs (it is not), nor because it comes anywhere near any Cabernet Sauvignon, or even Merlot or Malbec, on the scale of intensity or body.

Cinsaut, like Picpoul Blanc among white wines, is currently clicking in the wine market because it is, curiously, "Cinsaut," much like a rose is a rose. It produces a soft tannin red wine of moderate color; round yet zesty—as zippy in natural acidity as most Pinot Noirs and Zinfandels—while possessing its own aromatic profile suggesting brightly scented berries, a touch of strawberry and cooked rhubarb, and almost always notes of sweet kitchen spice (clove, mace, pepper). The sum total is so compelling, it makes you want to drink up at one moment, and slowly sip, ponder and savor in another.

Put that all together, and it still might not add up to much, at least to fussy red wine lovers. You can, in fact, accurately describe Cinsauts as "easy drinking" reds. Yet, in recent years, every time I pour a bottling of Cinsaut from one of Lodi's vineyards for someone who has never tasted one before, 99% of the time they are completely enthralled; their reaction akin to, "where have you been all my life?" Most people can't put a finger on it—that a wine that comes across as unsubstantial should taste so... substantial. The feeling is visceral.

Lorenza Wine's Melinda Kearney and Michèle Ouellet Benson sampling their neutral French oak aged Bechthold Vineyard Cinsaut in the cellar.

Otherwise, all important grapes need to be considered in context of terroir because good wines only come from good vineyards. Cinsaut, after all is said and done, is a grape of Southern France, where it primarily goes into the production of dry rosés, usually blended with other black skinned grapes such as Grenache or Mourvèdre. There are, in fact, a number of wonderful dry rosés made purely or partly from Cinsaut grapes grown in Lodi, but it is as a red wine that the grape expresses a distinctive varietal identity that is as surprising as it is appealing.

In that sense, Cinsaut is almost something of a Lodi thing, although there are a good number of excellent red wines made from Cinsaut grown in South Africa (because soils and topographies where the grape is farmed in South Africa tend to be more challenging, it generally produces an earthier or more rustic style of the varietal than in Lodi); and since almost the entire coast of California consists of variations of Mediterranean climate, the varietal is grown and produced in other regions.

Cinsaut cluster on harvest morning in Lodi's Bechthold Vineyard.

At any given time there are close to two dozen brands producing first class reds from Lodi grown Cinsaut. At the top of the list are classic names such as Turley Wine Cellars, Sandlands Wine and Michael David Winery.

The grape ripens so effortlessly in Lodi, though, I would wager that you would find just as much pleasure and esteem in bottlings by BIRICHINO, Christopher Cellars, Estate Crush, Fields Family Wines, Jessie's Grove, Kareen Wine, Iconic Wine, Lorenza Wine, Marchelle Wines, Markus Wine Co., McCay Cellars, Monte Rio Cellars, Perch Wine Co., Onesta Wines, Perlegos Family Wine Co., Tizona (by Bokisch Vineyards), Two Shepherds or Ser Winery. Take your pick and enjoy!

Without a doubt, it is in Lodi where Cinsaut is evolving into a wine fulfilling the growing contemporary taste for sleeker, more svelte, snappier sensory qualities in red wines. "Bigger" is no longer automatically better. Thus, as time goes by, as the climate grows warmer and consumers more sophisticated, it will become a grape that only increases in importance to the American wine industry.

Mokelumne Glen Vineyard Blaufränkisch.

Blaufränkisch

Let's talk about another grape which theoretically should increase in importance, but hasn't. If anything, it is forever the proverbial long shot.

Of all the red wine grapes I've worked with over the years, not one has compiled as wide, and inexplicable, a variance between pure appeal insofar as taste vs. pure perplexity insofar as actual market recognition. Its drawback probably begins with its somewhat unusual name... Blaufränkisch. It is automatic for an average consumer to ask, what the heck is a Blaufänkisch?

In Austria, where red wines made from this cultivar are indeed bottled as Blaufränkisch, this native grape naturally produces vividly colored reds of often sturdy tannin, always energetic in acidity, and perfumes and flavors of berry liqueur-like concentration and occasional spices suggesting allspice, pepper, occasionally peppermint or the like.

Drew Huffine of Trail Marker Wine Company harvesting Lodi grown Blaufränkisch.

Most of what has been seen of this grape in the U.S. over the past 30 years has been coming out of Eastern Washington where, for all their wisdom, vintners chose to bottle their Blaufränkisch by its German synonyms, Lemberger or Limberger, which are equally strange sounding. At one point, believe it or not, there was an estimated 250 acres of the grape growing in Washington, although that number has reportedly shrunken to well less than 50. In the wine industry, if sales were driven by pure quality and value/price quotients alone, Washington grown "Lemberger" might have grown to be as big as Zinfandel or Merlot in California, but that was not to be. At least they gave it a shot.

What I know from practical experience (particularly my years in the restaurant industry) is this: Once most open minded wine lovers put nomenclatures aside, the intrinsic quality of Blaufränkisch become crystal clear: Invitingly redolent, sprightly, spicy red wines, as sumptuously textured as, say, many Pinot Noirs, while retaining a grippier feel on the palate than most Pinot Noirs; and as intensely aromatic in fresh berry qualities as, say, any Zinfandel or Merlot, although without the weightiness or sense of overly ripened fruit found in most commercial Zinfandels, nor without the excess oak hoisted upon most California (or Washington) Merlots.

The "blau-blau" label of Haarmeyer Wine Cellars Lodi Blaufränkisch.

While traditionalist may disagree, by my estimation Bläufrankisch has as much of the right stuff for New World winegrowing as any red wine in the world. It seems inevitable that Lodi, of all the crazy California wine regions, should be the one to stubbornly cling to the grape's potential, notwithstanding the slings and arrows of invariable misfortune.

Granted, everything we've seen so far from Lodi has been coming from a single riverside vineyard, called Mokelumne Glen, its grapes going to just a few tiny handcraft brands. Yet in bottling after bottling, the promise of the varietal in a Mediterranean climate zone has been made abundantly clear: Under Lodi's steadily unclouded summer sunlight, the grape yields brightly flavorful reds with a somewhat effortless balance of natural acidity and restrained tannin/alcohol structuring. As it were, very much a contemporary taste preference.

Mokelumne Glen Vineyard's equipment shed sitting alongside blocks of Grüner Veltliner, Blaufränkisch and other grapes going into contemporary style wines which may eventually begin to play a bigger role in the California wine indusgtry.

West Sacramento's Haarmeyer Wine Cellars has recently been producing a bottling jovially nicknamed "Blau-Blau," suggesting the "glug-glug" of wines that go easily down the hatch. Yet the Haarmeyer bottlings have not exactly been glug-glug. Instead, they have been dense, sturdy, even a little prickly in a lively sort of way; "easy" only in in terms of their refreshingly moderate weight (barely 12% ABV), but plenty, plenty intense.

Is this the dawning of an age of Blaufränkisch? I doubt it. If only the grape had another name, like "Cabernet Sauvignon" or "Merlot"—unfortunately, already taken. Then again, the very fact that Blaufränkisch doesn't really resemble Cabernet, a Merlot, nor Pinot Noir or Zinfandel, should be precisely why it is bound to catch on, should consumers ever evolve to a point where names mean less than what is actually found, quite jovially, in a bottle.

Ah, Lodi... where hope springs eternal.

"Cane fire" red leaves in Lodi's riverside Mokelumne Glen Vineyard.