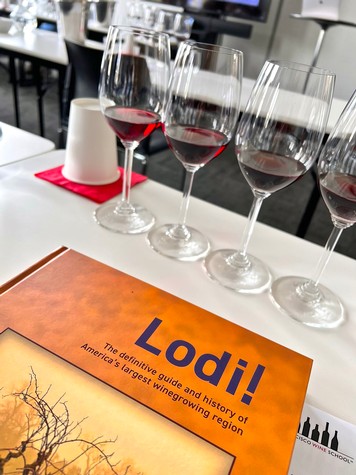

Letters from Lodi

An insightful and objective look at viticulture and winemaking from the Lodi

Appellation and the growers and vintners behind these crafts. Told from the

perspective of multi-award winning wine journalist, Randy Caparoso.

How to be a pompatus of wine

Lodi winemakers at work (Markus Niggli, Layne Montgomery).

For me, moving to Lodi fifteen years ago was a conscious act of embracing my inner wine lover. There were practicalities. At the time, I was hooked on Zinfandel as the best possible everyday drinking wine, and Lodi was where nearly half of California's Zinfandel was grown.

Mind you, by then I had already been around the world and had the privilege of walking through many of the world's greatest vineyards and wine regions, as part of my previous career as a restaurateur.

After my first visit to Lodi in 2002, I was puzzled. I didn't quite get the appellation's long established reputation as a "jug wine" region. Why? Because I knew that back in the 1960s and '70s, most of the grapes growing in Napa Valley and Sonoma County used to go into jug wines, yet no one thought less of those regions. To paraphrase the line from a Leonard Cohen song about taking a diamond to a pawn shop, that don't make it junk.

Vintage (circa 1960s) gallon glass jug bearing the Famiglia Cribari label, sourced from Lodi grown grapes.

Anyone with two eyes, a palate and common sense could see that there are vineyards here, thriving in phenomenal terroirs, that are as special as any in the world.

Especially old vines (i.e., for California, any surviving vineyards planted before the 1960s), which seem to grow wild and free, like the unkempt hair of rocksters or unshaven faces of movie stars, as opposed to more recently planted grapevines constricted by neat, tidy wires and trellises. The fact that there are far, far more old vines in Lodi than anywhere else in California, therefore all of America, is a statement in itself. It is such a good place to grow grapes, grapevines here they can live long and prosper.

Basic misconceptions of climate, grapes and special attributes

Still, you hear things all the time, like Lodi is a "hot climate," which suggests super-ripe, high alcohol wines with no freshness and little sense of balance. The fact that there are now many exquisitely balanced, restrained, finely delineated handcraft wines currently coming out of Lodi is absolutely exploding that myth into smithereens (see our previous post on Four contemporary varieties foreshadowing the future of California wine). Lodi has even become the home of pure, uncut styles of Zinfandels, particularly vineyard-designate bottlings aged strictly in neutral oak; which, as it turns out, are among the most delicate, and zestiest, in the state—something keen Zinfandels aficionados are well aware of.

Century-old Lod Zinfandel which, sadly, no longer exists; the vineyard recently uprooted and replaced by an almond grove.

What is more nonsensical is the very notion that "hot climate" is bad. A common problem is the basic misconception of the impact of climate on grapes and wines. It is true that in cooler climates it is more possible to grow grapes with higher acidity. Therefore, if you grew, say, Pinot noir in the French regions of Champagne or Burgundy, it would be a higher acid grape than it would be in warmer climate Southern France. Pinot noir, however, is not grown in Southern France—it wouldn't make sense. Instead, the Southern French specialize in grapes such as Grenache, Mourvèdre or Piquepoul, which retain more than enough acidity in warm climates. By the same token, Grenache, Mourvèdre or Piquepoul are not grown in Champagne or Burgundy—that would not make any sense either because those grapes would never ripen there. They would be too high in acid!

Wine grapes, in short, thrive in the climatic regions to which they are best adapted.

This is why, when you meet vintners from regions such as the South of France, the lower half of Italy, most of Spain or Greece, they all gleefully brag about their "hot climate." Anyone who appreciates wine on a global scale knows there are numerous great, great wines coming out of those parts of the world. Wines made from the appropriate grapes that are not only as fresh and well balanced as any in the world, but are also astounding in their diversity and special attributes.

Wine aficionado at recent Lodi ZinFest.

Secondly, the California regions closest to Lodi not only geographically but also in terms of temperature and climate include at least a third of Napa Valley and Sonoma County, and most of the Sierra Foothills and Paso Robles. I would say that the wines coming out of those regions are pretty good... just like Lodi's.

Still, Lodi is not the same as Napa Valley, Sonoma County, the Sierra Foothills or Paso Robles. Who in their right mind would want all regions to be the same, producing the same kind of wines? While Lodi possesses multiple terroirs, one thing it has that you won't find anywhere else—and where all of the region's vaunted old vines are cultivated—is a deep sandy loam soil, as rich in vigor as it is in efficient drainage.

Open up any book on wines of the world and you will read that most of the world's best vineyards, more than anything, possess well drained soils where grapevines can put down deep roots. This makes for healthier grapevines, which produce higher quality wine. Lodi's sandy loams are not just efficient, they are anywhere from 50 to 100-feet deep. You will not find anything close to that phenomenon anywhere else in the world, let alone California.

Old vine Lodi Zinfandel vineyard being uprooted for lack of demand.

Stormy weather

Lodi, though, is different, and it's differences (not similarities!) that make it special. While I may be speaking enthusiastically about one wine region, it doesn't mean I am tone deaf to the current overall state of the entire California wine industry. Rome appears to be burning all around us. Take the February 28, 2025 Los Angeles Times report entitled Changing tastes, cheap imports, a looming Canadian boycott. A ‘perfect storm’ for California’s wine industry. Stormy weather indeed.

The LA Times article cites Craig Ledbetter of Lodi's Vino Farms, one of the state's largest, most successful vineyard owners and farm management companies. A quote:

Craig Ledbetter, a third-generation farmer who owns and manages about 18,000 acres of wine grapes from Mendocino to Santa Barbara, says he left more than 10% of the grapes in Lodi unpicked last year [in 2024]. He also ripped out several hundred acres of vineyards in Lodi and elsewhere, permanently removing them from production, while also planting more pistachios.

“We see the writing on the wall,” he said.

Craig Ledbetter of Lodi's Vino Farms in front of his sustainable/Biodynamic farmed The Bench Vineyard.

Even while the entire California wine industry, not just in Lodi, is on the run like a cowboy movie desperado bereft of friends and hiding places, Ledbetter has been busily planning his family business's next move. Adds the LA Times:

The wine industry is starting to do more to try to attract younger customers. Ledbetter’s Avivo winery in Sonoma County, for example, is devoting more acres to regenerative farming and producing organic wines that use less Brix, or sugar, to bring down the alcohol content.

“The younger generation—they want to know what’s in the fruit, what they’re drinking, is it better for the environment?” Ledbetter said.

Does it make sense for this one grower to hone in on the quality of his farming and product while most of the industry appears to be running for the hills? It does if, as it is for the Ledbetter family, grape growing and wine production is in your blood. If it's what you do, it's time to get smart, not panic or lay down and die.

Sisyphus and rock. greekmyths-greekmythology.com.

No joke

For some reason, while pondering the current Sisyphusian challenges of growers such as the Ledbetters, I couldn't help but think of the song The Joker, which was a huge (and unexpected) #1 hit for the Steve Miller Band back in 1973. Even if you weren't yet around then, you probably know the song well because of its universally recognizable beat (complete with random cymbals), roller coaster bass and soaring slide guitar licks, while Miller sings those first immortal lines:

Some people call me the space cowboy

Some call me the gangster of love

Some people call me Maurice

'Cause I speak of the pompatus of love.

The thing about this, of course, is these words make little sense, at least if taken literally, other than the fact that Miller did previously pen songs called Space Cowboy and Gangster of Love. But what the heck is "pompatus of love?" Good question. While "pompatus" itself may mean nothing, every English speaking person in the world probably knows exactly what he's talking about. Within the context of the music, the phraseology strongly expresses a royal representation of the joy, the glory, a splendor... the passion of someone whose love is generated by music, in this particular song, driven by these particular slide guitar riffs, this maingroove bass line, those swaggering words... we get it.

Classic Steve Miller Band.

I once read, in fact, that Miller started his first rock band (with Boz Scaggs, no less) when he was 12, which was when they first started going out on gigs (they used to put on Ray-Ban sunglasses to hide their baby faces). Like grape juice and wine for Lodi's Ledbetter family, rock and roll has surely been infused permanently in Miller's blood, and it would have stayed that way even if he never got a #1 hit in his life.

Therefore, I like to think that when I speak of wines, grapes and a wine region that not everyone appreciates, in a way I am speaking as something of a pompatus. Translated into appreciation of wine, it's how you can grasp the authenticity of a place, and the glories of its wine, without a literal grasp of what conventionally passes for prestige or an orderly conception of authenticity.

Growers such as Craig Ledbetter who persevere against the odds are like pompatuses of grapes. Old vine growers, who are constantly being told to pull out their unruly antiquated plants—their family heirlooms—are like pompatuses of vines. The small handcraft producers, whether homegrown or flocking to Lodi from outside for its diversity of grapes, and the treasures of near-forgotten vineyards, are like pompatuses of winemaking You don't have to understand any of it, much less care about what many people say. You just know..

Intuitive perception: Lodi wine lover looking at world through wine-colored glasses.

In the world of wines, that is to say, quite often what your senses tell you is the opposite of what you're told you're supposed to know. Some people might call this being counter-intuitive, but to me it's more like being intuitive. It is, in fact, how thinking people perceive the world, particularly their grasp of anything having to do with the arts—and good wine is often described as the combination of art and science.

We do not need, for example, any cogent reasoning or justification for feeling the joy of a song. Grasping a poem does not require a dictionary command of words. The exact composition of a dish is neither here nor there when it comes to enjoying food, just like you don't need an analytic mind to be caught up in the excitement of book's plot or the exhilarating visuals of a movie.

The eye of the beholder

By the same token, wine appreciation needs no literal explication of what consitutes quality. Case in point: Twenty-five years ago I was asked to speak at the EPCOT International Food & Wine Festival at Walt Disney World in Florida. I presided over a wine dinner, a seminar with no more than a couple dozen wine lovers in attendance, and was asked to lead a larger event in which approximately 200 people were seated under a giant tent, awaiting my pearls of wine wisdom.

Visiting wine influencers tasting Mettler Family Vineyards' Lodi Cabernet Sauvignon.

Wine geek that I am, I opted to treat the bigger audience to a professional style "blind tasting." The objective being: By learning how to taste wine under conditions of not knowing what it is, anyone can become "their own wine professional."

I picked two wines for the blind tasting: A Napa Valley Cabernet Sauvignon retailing for $150 in the EPCOT wine store, and a Chilean Cabernet Sauvignon retailing in the same store for $12. After pointing out all the sensory qualities found in both wines, I asked everyone the most important question of all: Which wine do you prefer?

Young wine lover, ancient Lodi grapevine.

Approximately half the people raised their hand in favor of the $150 Cabernet Sauvignon, and at least half the people raised their hand for the $12 Cabernet Sauvignon. Of course, I told the latter group, "Congratulations, you just saved yourself over $100 while still ending up with the wine you like better."

Point being: Although the price of wines has a lot to do with factors such as cost of production, the vagaries of supply and demand and, in many cases, the perception of a wine's "prestige," ultimately price has little to do with actual quality perceived in a bottle.

Wine scholars at Lodi's Klinker Brick Winery.

The Billie Eilish principle (learning to crawl)

There is, as an old saying goes, absolutely no accounting for taste, which is why consumer tastes can be notoriously fickle, and unpredictable, no matter how much money anyone throws at it. To use another musical analogy: It may take untold efforts involving renowned singers and an entire orchestra of musicians trained over lifetimes, taking up hundreds of hours of studio time to produce a good classical record; but as a consumer, you may very well prefer the music of a solitary, unknown, self-trained artist wrapping up a recording in the privacy of her bedroom, just in a matter of minutes (can you spell Billie Eilish?).

Personal taste is funny that way. The trick, for everyone, is to discover what that taste is. The senses don't care about extenuating circumstances. It plows right through that. If something is good, it is good; or as Eilish would say, duh. Why is it so easy to understand this, like we do with music, books or art, when it is so hard with other things, such as wine?

For most people, I think the big issue with wine is mistrust of our own taste, which probably worsens as we grow old. As kids, for instance, we pretty much know exactly what we like and don't like. But as we "grow up," it is like we are almost bludgeoned into submitting to more socially acceptable standards. We are told what we are supposed to like; and sadly, we usually believe it. It's like we get dumber, not wiser.

Young, newly "discovered" Billie Eilish.

Wine is challenging because we're not even supposed to sip it until we're at least 21. By that time, it's like being a baby all over again. Developing a taste for wine is like learning how to crawl, then stumbling across a room like a drunken fool. This could be a good thing or a bad thing: Good, if we manage to retain trust in our own tastes; bad, if we adopt other people's preferences as our own.

Example: 25 or so years ago the "Cabernetzation" of American wine tastes was already well underway, and not much has changed since then. The other day I was presented with a couple of American grown Cabernets, both proudly retailing for close to $100, and both tasting perfectly awful. That is, they were dry, coarse, tough red wines, smelling more like canned vegetables and furniture polish than the compellingly deep or enthralling characteristics most of us at least hope to find in high class wine. Yet the pervasive message pushed by the wine industry itself is that we're supposed to love and appreciate wines like these, even if they taste rough, vegetal, or like sticks of dried wood.

Mind you, this is not to begrudge the fame, critical acclaim or price status attained by many of today's coveted wines. Nonetheless, being told we're supposed to like certain wines is like being told we must love the latest James Cameron or Ridley Scott movie. That we must enjoy watching Gordon Ramsey or Bobby Flay, or wearing the latest fashions of Ralph Lauren or Chanel. When, in fact, as much as we may admire or appreciate all of that, we may not actually like them.

Old time wine buffs at San Francisco wine festival.

Mass hysteria among consumers and professionals alike

Wine drinkers are perhaps the most notorious of consumers when it comes to what I call "mass hysteria consumption." I've lost count of the number of times when I've stood in a ballroom with as many as a thousand other people, tasting wines presented by this famous winemaker or that, watching everyone going ooh-and-ah over wines which I, myself, found bland, boring, or even just plain bad!

I have my own little theory as to why this happens: It's not that most people don't know a good, or bad, wine when they taste it. It's just that most people don't trust their own instincts. They've become conditioned to believe that they, themselves, can't possibly be harbingers of good taste, and so they leave it to others to decide that for them. Many of them end up drinking wines they don't even like; or even worse, they stop drinking wine altogether because they don't like the wines people keep telling them they should be drinking.

That shouldn't happen, but it does. Never, ever let anyone—be it me, the best known "Masters," respected journalists, or even what seems to be the consensus among thousands of other wine drinkers—tell you what wine tastes best for you. No matter how reputable or expensive, if a wine tastes bland, boring, or just plain bad, chances are this is because the wine is bland, boring or bad.

Visiting sommelier tasting ancient vine Lodi Zinfandel at its source, the vineyard where the wine was grown.

In other words, your own palate is almost never wrong, just like your ears aren't wrong when you pick up on a favorite song, or an annoying one, and your eyes aren't deceiving you when you fall asleep during a boring movie.

How do you discover the wines that bring tears of joy rather than boredom? Same as you would anything else: Find friends, colleagues or professionals who seem to have similar tastes, or at least understand yours. Yes, it is possible to find simpatico minds in wine stores manned by specialists who have steered you right in the past, or certain restaurants with wine lists highlighting a larger portion of wines to which you seem to be drawn.

Wine "professionals" are exactly that: They make their living knowing wines and bestowing that largesse on people who just want some decent advice. The trick, though, is recognizing when professionals just don't have the same taste as you, or else are not competent enough to get the memo—that your taste is more important than theirs. Whenever you reach a point where someone else's advice is clearly not doing you any good, you just have to move on—no different than finding a hair stylist who understands your "look," or a record store owner who knows the vinyl you want.

Vintage music for wine (and cigarette) lovers.

Of course, I'm one of those who makes a living out of wine, and talking about it all the time; in my case, the past 47 years. If anything, I have always said with complete confidence: There is a lot bad wine advice floating around out there. I know this because I'm constantly hounded by advice, too. I, too, get the endless pitches, and have spent most of my career tediously separating the proverbial wheat from the chaff.

It's not that any wine professional means to dispense errant advice. The vast majority of them are well meaning and got into it mostly for the love. What I do know, though, is that most wine professionals are all too human. They, too, fall under the sway of a "crowd"—in their case, entire circles and worlds of other wine professionals who are supposed to know better, thus held in varying levels of esteem, most of it arbitrary.

Don't go near the Kool-Aid

Let's be brutally frank about this: The entire world of commercial wines is most definitely shackled by a status quo. Absolutely brimming with wine professionals or scribes going about their business by simply repeating what other professionals or scribes are saying, mostly because it's a lot easier to go with majority opinions than to forge your own. This is not to say that wine related industries are completely bereft of individualism or creative thought. Many winemakers, like artists or musicians, have quite a bit of spark in them. Nonetheless, the wine industry is, first and foremost, a business, which makes it hard for individualistic vintners to break through conventions.

Yet you and I know that absolutely anything that falls within the realm of the senses is not completely compatible with convention. Human beings love creativity and imagination, the more unique and unexpected the better. The very definition of "the arts" is that they are beholden to the eye—or ears, mouths and minds—of beholders. And personal taste is exactly that: Personal. Only you know what you truly like, or abhor. Good wine, in particular, is not like Kool-Aid—you don't drink it just because someone tells you to. If you did, you'd be a fool, like crowds of people cheering on an emperor walking around without any clothes.

This is exactly why, when I say Lodi grows and produces wines of genuine authenticity, I don't think it matters what the conventional thinking is. Many wine lovers already know what's in their heart. At least those freed from the notion that matters of taste are supposed to be uniform or universal.

Your senses never lie. You know when something is good, or captivating, the same way you know what pompatus means. Let's call it being a "pompatous of wine"... finding comfort in a place where you are right here, right here, right here, right here at home.

Lodi wine lovers.