Letters from Lodi

An insightful and objective look at viticulture and winemaking from the Lodi

Appellation and the growers and vintners behind these crafts. Told from the

perspective of multi-award winning wine journalist, Randy Caparoso.

Why big, oaky California whites have always been food-worthy

Coopering oak barrels, the use of which drastically altered the style and scope of California wine in the 1970s and '80s.

Nowadays we talk a lot about crisp, light, minimally or "non" oaked white wines. That's because they represent cutting-edge wines becoming increasingly associated with Lodi. We push that fact because we want to explode the myth that Lodi only produces big, fat, ultra-ripe wines. This is not, however, to take away from fuller bodied white wines that are often less sharp in acidity, and often perceptively or even generously "oaky."

Not too long ago (where does the time go?) people often referred to those kinds of wines as "cougar juice." Full bodied, buttery or creamy textured white wines often drunk more as cocktails than with food. Guess what, though? These wines can also be wonderful with food—lots of dishes most of us love to eat.

Over the recent decades, big oaky white wines were often criticized, mostly by factions that have knee-jerk reactions to the notion of popularity. As if it was plebeian; the idea that a majority of people can't possibly have "good taste." It's absurd, but what can we do, except talk about it?

"Cougar juice" (i.e., buttery oaked Chardonnay). sommgirl.com.

"Vins des Cowboys," is how I once heard California wines in general described by a British Master of Wine, way back in 1981. In retrospect, I can understand why Europeans might have thought that of the entire California wine industry. The 1970s and 1980s were definitely a time when California growers and vintners were still feeling their oats, constantly experimenting and “discovering” new and exciting ways of crafting wines.

At the time I was working in restaurants, first as a waiter, then as a sommelier. The sudden interest in California wines was so palpable by the mid-1980s, it was as exciting to consumers as it was to the vintners themselves. To paraphrase that old Western song by MIchael Burton, they "must have gone crazy out there." And they did.

Recently, when dusting off one of my old wine journals from the early 1980s, I read my notes on an experience at a (then) newly opened wine bar in Honolulu named, appropriately enough, "Grape Escape." That night we sampled two white wines made by brands that were considered hip, new and exciting: One was typically big, blustery Napa Valley Chardonnay, the other a pungent, oak-aged Sonoma Valley Fumé Blanc.

Barrel fermented and aged Chardonnay in a pioneering Napa Valley winery.

By themselves, according to my notes, the wines were exceptional. I wrote down "complex," a popular descriptor used in those days for when we found a wine to be multifaceted, although we might not have been able to put a finger on exactly why that was. I think, now, most likely it was because both wines were strong in oak flavors.

The early '80s were a time when California wineries were so excited about the taste of oak in their wines, they used it the way today's teens might drench themselves in Ariana Grande perfume or Axe body spray. I also wrote down "intensely varietal" for both wines—in those days, the stronger the smell of a grape, the better. Between the oakiness and fruitiness, California wines used to come across more like avalanches than gently babbling brooks.

While both wines were impressive, apparently we were not so excited once our our food was served. We had ordered filets of the Hawaiian fish known as opakapaka, a pink snapper, which came slightly charred with sizzling butter and garnished with no more than fresh lemon, and no sauce. We loved it—the plainness of the preparation seemed emphasize the freshness and delicacy of the fish all the more.

Ripening Lodi Chardonnay in Michael David Winery's Bare Ranch.

What was disappointing, though, was the fact that the Chardonnay did not seem to add more to the taste of the fish than what the simple squeeze of lemon already did. In fact, the combination of the fish and wine in the palate came across as a little bitter, almost drying out the taste of the fish. Even then, we could tell that high alcohol (over 14% ABV, according to my notes) and oakiness of the Chardonnay was ruining the taste of our fish.

So we turned to the Fumé Blanc, which was crisper in acidity although not much lower in alcohol than the Chardonnay. All the same, a strong herbaceousness—a vegetal combination of cut green grass and dried hay—as well as vanillin oak veneer in the Fumé Blanc came across so aggressively that these components seem to blot out the delicate, flaky qualities of the fish.

Mind you, in those days, in restaurants, we were still selling light, mildly tart and dry white wines from France such as Chablis, Mâcon and Pouilly-Fuissé; although, progressively, fewer and fewer of them because most customers were more excited about our latest selections of California wine. What was crystal clear in that wine bar, though, was that a light, mildly tart and dry French white would have tasted a lot better with our opakapaka than the two hip brands of California wine in our glasses.

Two wine glass shapes designed by Riedel for Chardonnay: A narrower tulip for moderately oaked and balanced styles, and a wider bowl for fuller bodied, generously oaked styles.

Have things changed much since those days? I would say, yes and no. No, because the 1980s was such a crucial time of growth for California wine industry that the styles for the most popular varietal categories such as Chardonnay and Fumé Blanc became so permanently set, like a Sharpie on a shirt or a tattoo on your skin, many if not most of the commercial bottlings of those wines are still made that way, more than forty years later. It is understandable, of course, that more established brands would be reluctant to veer away from the styles that made these wines popular in the first place.

The answer is also yes, however, because many California wineries—especially newer ones that aren’t locked into styles more established brands seem to be stuck with—are now producing wines with, say, much more subtle oak character, if any at all, plus fruit qualities so subtle that they are often more minerally than fruity. One of Lodi’s most successful brands, for instance, specializes almost exclusively in light and crisp dry white wines, and they don’t use oak barrels at all! How we would have loved to taste one of these new fangled Lodi whites with that opakapaka.

Frank Prial, the widely syndicated, and oft-times cantankerous, wine columnist of the 1970s, '80s and '90s.

Back in 1981 a nationally syndicated wine columnist named Frank Prial seized upon the issue of California wines not complementing food with something of a malice. The way Prial described it, a repugnant “snobbism” had been spawned by the sudden emergence of California wines in those days, especially among the many consumers hailing them as the “best in the world,” as if they were cheering on Olympic athletes while shouting out “U.S.A!”. Consequently, by the early 1980s, there were already armies of “cultists" spouting a special language, or esoteric jargon, for whom wine appreciation was, according to Prial, more like "wearing clothes with someone else's name on them."

Prial went on to say that this “new breed” of wine lovers was especially “into Chardonnay,” California's "macho" wine. Prial saw them as aggressive, overpowering wines that, unlike the more subtle white wines of France, tended to "obliterate" food and were designed mostly to "outchard" other Chardonnays, particularly in wine competitions.

Prial’s jabs were accurate, but not entirely fair. At the time I thought he also lost sight of a point that even the subtle Europeans often repeat: That California wines, no matter what the commonalities, are simply not meant to be compared to French wines. The French don't even make comparisons of their own wines when they come from different parts of France, even if made from the exact same grape. Individual terroir (i.e., "sense of place") is that sacred to them. Ergo: If, because of distinctively different growing conditions, French and California wines do not taste the same, how can they be compared, even in the context of food?

Contrasting terroirs yielding contrasting styles of Chardonnay based whites (from left): France's Chablis (light, pure, minerally styles), Puligny-Montrachet (full bodied, oak enriched), and California's Russian River Valley (big, opulent, typically oaky).

In their quest for ultimate quality, California wine producers have always aimed high, without necessarily thinking “food compatibility.” With Chardonnnay, for instance, they have never seemed content to duplicate the classic, lighter styles from France, such as Mâcon or Pouilly-Fuissé; the thinking being, that if California Chardonnays can be more than “light, dry and crisp,” why settle for that? They would rather go for qualities such as “awesome" (a favorite word often used by the famous wine critic Robert Parker), which is how grands crus such as Montrachet, France’s rarest and presumably “greatest” Chardonnay based white wine, is often described.

Montrachet, in fact, has always been considered so divine by the French, it’s been said that you shouldn't even drink it with food; but rather, as Alexandre Dumas famously wrote, while “kneeling and with bared head.” No one ever demanded that macho-style California Chardonnays be drunk the same way. But if Montrachet—typically a generously oaked wine—is considered too big and important for food, why aren't the top California Chardonnays given the same leeway?

Chateau Montelena Chardonnay from the mid-1970s, an era of early apex for this brand and barrel enriched styles of this varietal.

After all is said and done, though, only one meaningful point has always remained true down through the years: California wines demand different food contexts; an understanding, as it were, going beyond even the old, time honored European standards. If that makes California wines more like vins de cowboys, so be it.

Speaking of big, oaky, fruit driven wines: While going through my wine journal from the 1980s, I found another entry describing what I thought was one of the best combinations ever, involving a bottle of dense, dominating, aggressively oaky 1975 Chateau Montelena Chardonnay. The matching dish was a home cooked rendering of Julia Child's ris de veau a la crème et au Champignon—a fancy way of saying sweetbreads (calf’s pancreas or thymus) in a sauce enriched by decadent whipping cream and mushrooms. Why? Because within the context of this dish, even a heavy handed Chardonnay like the ’75 Chateau Montelena came across as light on its toes, nimble as a dancing girl; the textured richness of the dish providing the grip that even lumbering styles of Chardonnay need to show off their best sides—that is, the full bodied, lusciously fruited profile that makes a California Chardonnay “Californian.” Notwithstanding the classic standards of the “French.”

Chanterelles, an exceptionally Chardonnay-friendly mushroom. bowtieduck.com.

Yet “big” wines do not necessarily have to be matched with “big dishes.” Back in the 1980s, for instance, cream of fresh mushroom soup was a staple in virtually every restaurant, especially French restaurants. We enjoyed many a California Chardonnay with simple bowls of mushroom soup, an unerring and dependable match. While in this case, mushroom soup serves as little more than a foil for a Chardonnay, it always brings out the layers of tropical fruit, vanillin oak, and creamy texturing typical of this California varietal. What can seem excessive in a wine can become subtle, even harmonious, in the right context. What’s not to like?

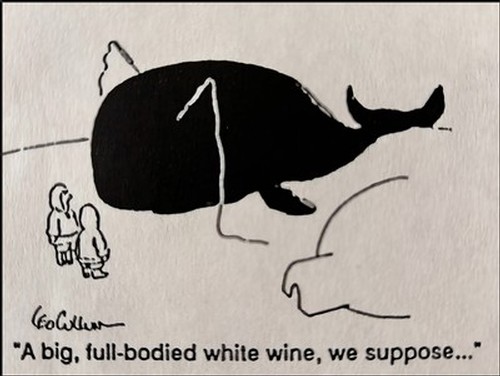

Leo Cullen, The New Yorker.

In a similar vein, during my years as a working restaurant sommelier I always considered one of my most successful “wine dinners” to be when we served a top brand of barrel fermented and aged California Chardonnay with veal chops braised with mushrooms, swimming in a buttery sauce. It was thrilling to see guests enjoying what I loved about that combination: To me, like a reflection upon a reflection in a crystal clear pool—the earthy meatiness of the mushrooms amplifying the flavor of the mild and fleshy veal, while both the veal and mushrooms fleshed out smoky oak flavors while even coaxing mildly acidic qualities in the California style Chardonnay (despite the fact that California Chardonnays were never known for their elevated acidity—at least not until recently).

White oak barrels sourced from forests of France, a first choice among specialists of barrel fermented and aged white wines.

Wherefore art thou California Sauvignon Blanc, often bottled as Fumé Blanc? Although the two names are synonymous on California labels, “Fumé” has usually been used when a Sauvignon Blanc sees some barrel fermentation and aging. The Fumé style of the varietal is also one often associated with Napa Valley grown Sauvignon Blancs, as opposed to those grown in, say, Sonoma County, Lake County, Lodi or the Sierra Foothills. Many Napa Valley producers want their Sauvignon Blancs to taste big and "important" (100-point critics are suckers for that), and oak barrels help them get there.

Be that as it may, the fuller, herbal, perceptively oak influenced styles of Sauvignon Blanc coming out of California are often too assertive for things like plain oysters, clams and mussels in natural broths, or more delicately sauced seafood dishes (re our early experience with Fumé Blanc with white fish served with no more than fresh lemon).

Fortunately, though, we have never have to look far for the types of dishes that work effortlessly with oak influenced Sauvignon Blancs—the everyday chicken. Ideal iterations have always included fresh, plump, relatively low fat roasters often found in gourmet or ethnic markets (such as Chinatowns or Little Saigons). Roasted simply with lots of butter, chicken gives aggressively “varietal” Sauvignon Blancs plenty to highlight its crisp, fruit driven, herbaceous qualities.

Roasted tarragon chicken. Sara Haas, allrecipes.com,

A classic Sauvignon Blanc-friendly twist is Julia Child’s poulet poele a l’estragon (once again, excuse my French!)—chicken rubbed inside with butter and a generous dose of fresh tarragon, and served in its own aromatic juices. In this case, the lavish use of ripe lemons as well as aromatic, green, anise-like herbs is also a wonderful way to highlight the airy fresh, lemony tart and green leafy aspects of most California Sauvignon Blancs, whether aged in oak or not.

Although we talk about delicious wine and food matches, do "perfect marriages” actually exist? Considering the endless range of wines, dishes and each and every person’s predilections, I would say there is no such thing as perfection, although there are many wine and food combinations that have a higher percentage chance of pleasing most people. You may, in fact, be a Francophile, and not think much of California wines at all, but still enjoy a California wine and food match when well put together. And as big, clumsy or wild, rough and tumble as California wines may be, I have always found that there is a good food match for virtually any version of so-called vins des cowboys.

Grilled fish, one way of preparing any white meat, has a high percentage chance of complimenting white wines fermented and/or aged in toasted oak barrels. kfoods.com.

Just for fun, at the end of this post you will find a list of a few more of our favorite dishes enjoyed over the years with the biggest, most aggressive styles of California white wines, especially barrel aged Chardonnays (besides Fumé Blancs, you can also throw in California grown Roussannes and Viogniers in this category of whites often strongly influenced by oak). I’m sure you’ll agree.

Certain food components go very well with these styles of wine: First, butter and cream for the simple reason that oak often adds buttery or creamy textures to white wines; by the same token, grilled dishes are easy matches because barrels are typically charred or “toasted” on the inside, a byproduct of how they are made (barrels are shaped by bending oak staves over open fires).

Other easy matches: Mushrooms (especially chanterelles, above the many others), soft creamy cheeses (from Havarti and mozzarella to brie, double and triple crèmes), corn, peas and green beans, leafy herbs such as sweet basil, dill and the components of fines herbes (parsley, chives, tarragon chervil), and milder nuts (macadamia, pistachio, almond, hazelnut, Brazilian) are all good food for thought when cooking or putting together spreads for fuller bodied whites.

Classic French oak influenced Chardonnay by Lodi's The Lucas Winery. pullthatcork.com.

Specific bottlings: Favorite oak enriched styles of Lodi grown Chardonnay include the likes of Harney Lane Winery’s Henry Ranch vineyard-designate, The Lucas Winery, Mettler Family Vineyards, Peltier Winery’s “French Oak” label, JSL Wines “Lorraine,” Lucid’s “Skin Contact,” and Oak Ridge Winery’s Maggio Family Vineyards bottling.

Other than Chardonnay, other oak influenced styles of Lodi grown white wines include include Covenant Winery’s Mensch Roussanne, Oak Ridge Winery’s 1906 Vintners Sauvignon Blanc, Anaya Vineyards Albariño and Mio Vigneto Ribolla Gialla. Also worth seeking out is the Kareen Wine Viognier, a Lodi grown white that is does not see any oak but is aged in stainless steel drums to achieve a fleshy, round quality not unlike that of barrel fermented whites.

Dependable match for Chardonnay: Mt Tam triple crème cheese by Petaluma's Cowgirl Creamery. Sara Remington, cheeseprofessor.com.

A few culinary blasts from the pasts involving full bodied, oak and fruit driven California whites:

• Fettucine alfredo

• Creamy garlic spaghetti

• Spinach Havarti mac and cheese

• Veal osso buco in dill chardonnay jus

• Wild mushroom mixes sautéed in fennel butter sauce

• Filets of white fish (especially mahi mahi) in roasted macadamia nut lobster butter sauce

• Cast iron seared salmon with creamed corn sauce and spring vegetables

• Outdoor grilled snapper with roasted sweet pepper, tropical fruit and cilantro salsa.

• Homemade burritos with smoked mozzarella, kalua pig (woodsmoked Hawaiian style pulled pork) and lomi lomi ("chop chop" tomatoes/sweet onions/green onions) or pico de gallo

• Kamado or Big Green Egg smoked Thanksgiving turkey

• Fines herbes chanterelle omelette with crème fraîche

• Truffled buttered popcorn

• Baked double or triple crème with honey and maple glazed nuts (almond, pecan or walnuts)

Lodi Chardonnay harvest in Michael David Winery's Bare Ranch.