Letters from Lodi

An insightful and objective look at viticulture and winemaking from the Lodi

Appellation and the growers and vintners behind these crafts. Told from the

perspective of multi-award winning wine journalist, Randy Caparoso.

A current list (over 100!) of wines that celebrate Lodi’s sense of place

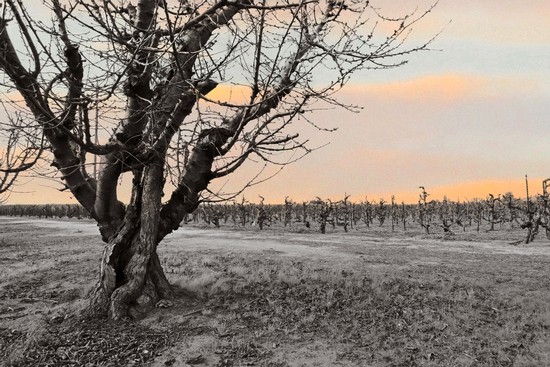

Late March blossoms in mixed old vine block sitting in the deep, rich sandy loam soil of Lodi's Mokelumne River AVA.

Night and day

You might want to pass Goal and scroll all the way down to the end of this post to look at the list of Lodi grown wines that strongly express terroir—the catch-all French term for “sense of place,” in reference to environmental factors defining vineyards and wine regions perceived in sensory qualities of wines. I currently count well over 100 of these wines, yet no doubt I missed a few.

Fifteen years ago if I made this list, I probably would have counted less than a dozen wines that I could honestly describe as terroir focused. Lodi viticulture and winemaking styles have changed that much—drastically.

Fifteen years ago the vast majority of wines grown in Lodi were made to taste like wines from other regions. The thinking being: A Lodi wine can be better respected if it is comparable to wines from places other than Lodi. Today, the finest Lodi wines are being made to taste like they come from Lodi, and Lodi only. An opposite objective. What a difference 10+5 years has made!

Working sheep in March among old vines in the Mokelumne River-Lodi appellation.

Terroir writ large and small

So let’s discuss. First, what do we even mean by “terroir focused?” Earlier this week when I was thinking of another way of explicating the concept, when into my box popped a short piece called An Apologia for Terroir in an Era of Tribalism. Composed by Meg Maker, one of the blogosphere’s more popular writers, posted on her page called, appropriately enough, Terroir Review. Maker’s erudite musings on the state of terroir in the world today:

Terroir writ large is about customs, traditions, and what the people of a land can pull forth from it. Food evolves to suit the landscape, the landscape evolves to suit the food. A dialectic.

Terroir writ small is concrete (soil, grapes, wine). Terroir writ large is abstract (taste, culture, norms ). Abstractions are unsettling.

Terroir is dismissed as elitist, bandied by wine writers to make their work sound important. It is decried as esoteric, abstruse.

Terroir is dismissed as Eurocentric, invented by the French and jealously guarded, not only the concept but the word itself..

Terroir is dismissed as old-fashioned, an historical artifact, a throwback to old dogmas. A nostalgic reflection of an older way of life that nobody remembers and is now told only in stories, mostly fictive.

Terroir is dismissed as insular, protectionist, reinforcing an us-them dichotomy. This is the most troubling critique given our era of political factionalism, because it can drive away the open minded, the open hearted. This has prompted me to interrogate my preferences, my favoritism of autochthonous [i.e., indigenous] grapes, of traditional forms, historic precedents. Does respect for terroir teeter on tribalism, on blood and soil nationalism? Or does it demonstrate the opposite: a simple reverence for enduring truths that somehow manage to stay relevant?

Terroir evolves, adapts. It is a vital concept, alive and always changing, especially as the globe warms. Its practitioners, its adherents, must be nimble, engaged in an ongoing dialogue between themselves and their place. Which makes terroir a thoroughly modern idea.

Dropped Cinsaut sitting on Lodi's vaunted sandy loam soil in the 25-acre Bechthold Vineyard—own-rooted vines planted in 1886.

The state of terroir for a region like Lodi

Within all of the world’s major wine countries there are multiple regions constantly competing for attention. Wine, after all, is not just an adult beverage, it is big business, and if you want to compete in business well enough to survive—and better yet, thrive—then you’ve got to shout out your positive attributes from the highest proverbial mountaintop.

The attributes that make every region distinctive are essentially terroir related. That is, all the things that you can find in the vineyards, the appellations as well as the sensory qualities of resulting wines that make each region unique, including their history and traditions (grapevines, after all, don’t grow on their own, and wines don’t make themselves—they all require human input). Distinctive attributes, ultimately, you are less likely to find any other regions.

The irony of Lodi is that it is such a natural region for cultivating wine grapes that it grew into the largest in the country, its total acreage approximately the size of all of Napa Valley and Sonoma County put together. For that reason, Lodi is utilized by the American wine industry to produce most of the commercial wine consumers actually buy; namely, the $8, $10, $12 to $18 bottles you are most likely to find in stores and on supermarket shelves across the country.

The sustainably and biodynamically farmed The Bench Vineyard in Lodi's Clements Hills AVA.

The value priced wines bought by American consumers are not, however, sold by distinctions related to terroir. They are sold primarily by branding and, in the case of labels identified by the names of a grape, a concept called varietal character. If, for instance, you buy a Woodbridge by Robert Mondavi label Chardonnay, you can expect a good, medium bodied, more or less dry style of white wine that tastes like, well, “Chardonnay.”

The goal of the Woodbridge brand—which, incidentally, is produced in Lodi, more than 90% of its wines sourced from Lodi vineyards—is not to sell you a product that tastes like it comes from Lodi. The objective is, simply, that you like the Chardonnay enough that you’ll buy the same brand over and over again. This is American style wine marketing 101.

This, however, is not how wine regions compete. The goal is differentiation, not sameness, regardless of perceived prestige. While its practical goal is authentication, France’s entire, sprawling system of Appellation d’origine contrôlée (AOC) is based upon aesthetic principles of differentiation. You don’t “rate” or rank regions—the appellation system is set up to give consumers a reasonable expectation of what to expect in bottlings grown in each region, even if individual producers are striving to distinguish themselves. The same goes for Italy’s Denominazione di origine controllata (DOC), Germany’s Qualitätswein system, and Spain’s Denominación de Origen (DO), where the emphasis is on regional distinctions, often drilled down further to individual vineyards.

The rolling, rocky clay hillsides of Lodi's Borden Ranch AVA.

In the U.S. we have our own evolving, albeit less rigid, system of American Viticultural Areas (AVA). Consequently, terroir related sensory distinctions pertaining to wines of each AVA are still vague at best. The concept is still new for the United States. That does not mean, however, that terroirs do not exist in this country, and the relatively "infant" nature of the American wine industry has not discouraged a growing number of growers and vintners from trying to carve out regional or vineyard focused identities. They're getting the hang of it, and more and more consumers are catching on.

Case in point: While Lodi as an appellation identified on a wine label may not have as much cachet as “Napa Valley” on a label, the fact of the matter is that, slowly but surely, Lodi is receiving more recognition as a wine region because there are now more wines than ever that possess sensory qualities that are distinctly “Lodi.” Meaning, evincing qualities that cannot be easily duplicated in other regions, such as Napa Valley or Sonoma County, Barossa Valley or Maipo Valley, Finger Lakes or Ancient Lakes, or any other part of the world.

I would say that, just thirty years ago, consumers had no idea of what a wine from Lodi tastes like. Today, they have a much better idea. This is how the formulation of terroir, a concept identified with all wine regions of note, works, and it is enhancing how the world thinks of Lodi.

Sampling of handcraft, low intervention style brands and varietal bottlings sourced from Lodi vineyards, appealing to more and more of today's consumers.

The evolving tastes of consumers

While most American wines are still produced and sold primarily on the basis of branding or varietal character, the tastes of many consumers have also been evolving in ways that have caught even much of the wine industry by surprise. Not only are they starting to identify sensory qualities associated with specific American wine regions, they are basing more and more of their buying decisions on those expectations. As a result, consumer preferences in respect to how wines are grown and crafted are also changing. In what ways? Let us count a few:

1. There is a small yet significant consumer appetite for less commercialized style wines, in favor of wines that are less predictable and more “handcraft”—as vague as that concept might be, it has been driving consumers to smaller brands that do not compete on a large, mass market scale by producing wines slavishly following standard industry norms.

2. A growing taste for low intervention style wines, often described as “natural”—the latter, a term still castigated by much of the conventional wine industry because of its vagueness, nonetheless sought by more and more consumers, many of them seeking alternative style wines for the sake of alternative style wines (note: many of today’s best natural style American producers never mention the world “natural”—they’re just trying to make wines that are mucked up as little as possible by minimizing “adds” such as cultured yeasts, enzymes, water, acidification, filtration, barrels, oak adjuncts, and many of the other tools routinely employed by conventional brands to achieve consistency).

Clusters of Grǔner Veltliner, among the over 100 grape varieties now commercially grown in Lodi, bottled by handcraft producers.

3. Increased consumer interest in less mainstream varietals or blends—for instance, in Lodi there are now more wineries bottling Albariño and Tempranillo than Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Pinot Noir, Chardonnay or Sauvignon Blanc, mostly because Albariño and Tempranillo grow so well in Lodi, but also because consumers who shop “Lodi” now identify the region as a source for alternative varietals.

4. Increasing consumer consciousness in support of producers prioritizing sustainable, organic, regenerative or biodynamic farming as part and parcel of growing commitment to low intervention wine production on the part of vintners.

5. Last but not least, growing interest in wines that taste more like where they come from (namely, terroir), rather than a predictable brand style or some sort of varietal character.

Own-rooted, ancient vine (over 120 years old) Zinfandel now going into minimal intervention style, vineyard-designate wines crafted to express Lodi's Mokelumne River terroir.

Old vines and proliferation of grape varieties

Over the past five to ten years the concept of “old vines” has also become a talking point, as much for consumers as for the industry. This, in many ways, has raised Lodi’s profile as a wine region because there are more old vines in Lodi than anywhere else in the United States. The reason for that is because the environment in Lodi is conducive to grapevines being able to sustain long, healthy, productive lives—something that has more to do with Mother Nature than human proclivity. Technically, in California, a vineyard is considered “old vine” when it is at least 50 years old, although there are some vineyards in Lodi planted over 100 years ago.

One of the other peculiarities of old vine viticulture is that, generally speaking, the older the vines, the more likely a wine produced from those vines are able to retain sensory qualities that reflect terroir. All Lodi grown Zinfandels, for instance, tend to fall on the floral side of the grape’s varietal character, and ripen with a soft, rounded tannin (i.e., phenolic content) structure. So in Lodi, the older the vines, the more floral and roundly textured the wine. Furthermore, old time growers in Lodi have always known that old vineyards located on the west side of town are almost always earthy, whereas old vineyards on the east side of town are more red berry scented, and rarely earthy.

East side, west side, it doesn’t matter: Lodi grown Zinfandels in general are more gentle and floral than Zinfandels grown in Napa Valley, Sonoma County, the Sierra Foothills or anywhere else in California. It’s no different than the fact that Polynesians tend to have brown skin and Scandinavians extremely white skin, yet all are Homo sapiens. It’s a small world after all. Hence, the differences between Zinfandels grown in different places is entirely terroir related—the phenomenon of “place” we keep harping on. It is producers who emphasize those differences by applying less interventionist methodology who are perking the growing interest in terroir.

Historic Vineyard Society sign marking Clements Hills-Lodi's Stampede Vineyard, an own-rooted old vine Zinfandel growth yielding wines with a specific sense of place attracting a good number of small, artisanal style producers and their growing following.

One of the other manifestations of Lodi’s natural environment is that it is conducive to a wide variety of grapes. Make no mistake, though, other regions in California—such as Napa Valley, Sonoma County, Paso Robles or Santa Barbara—are perfectly capable of growing over 100 different grape varieties, since they all share a Mediterranean climate similar to Lodi’s. The reason you find more grapes commercially grown in Lodi is because it is more economically feasible to do so than in other regions.

The cost of planting and farming, plain and simple, makes it possible to do in Lodi what you can’t in other regions: To profitably cultivate grapes such as Albariño and Tempranillo, Grenache noir or Grenache blanc, Piquepoul and Cinsaut, near forgotten historic grapes such as Mission and Flame Tokay, and even oddities (at least for California) such as Pinotage and Zweigelt, rather than being relegated primarily to higher priced, well known grapes such as Cabernet Sauvignon or Pinot noir.

Therefore, to a large extent, wines made from alternative varieties still considered a little out of the mainstream are also representative of Lodi’s unique terroir. Many of today’s small, handcraft, alternative style producers are sourcing the wide range of grapes being grown in Lodi for exactly that reason.

Late winter among ancient vines (over 120 years old) and a stand of Bing cherry trees, another crop that thrives in Mokelumne River-Lodi's rich, deep alluvial soil.

Wines that “celebrate” Lodi

I was recently asked by a local restaurant of some prestige to put together a wine list that they can call “Celebrating Lodi.” This got me set on the thought process: What are the wines that are well made and “low intervention” enough to express their Lodi identity in the most vivid or distinctive fashion? In other words, terroir?

If you are as curious about these wines as much as a growing number of other consumers, you would do well to search out the following sampling of what can be currently found, all wines that practically scream “Lodi!” from the tips of their noses to the bottom of their punts:

• 2023 Bokisch Vineyards, Clay Station Vineyard “Miravet,” Borden Ranch-Lodi Verdejo

• 2023 Peltier Winery, Lodi Vermentino

• 2023 Monte Rio Cellars, The Bench Vineyard, Clements Hills-Lodi Vermentino

• 2023 Terah Wine Co., The Bench Vineyard, Clements Hills-Lodi Vermentino

• 2022 Avivo, The Bench Vineyard, Clements Hills-Lodi White Wine (Vermentino)

• 2022, JSL Wines, Manna Ranch, Mokelumne River-Lodi Marsanne

• 2022 Markus Wine Co., Mokelumne Glen Vineyards, Mokelumne River-Lodi Nativo (Kerner, Bacchus)

• 2023 Lorenza Wine, Clements Hills-Lodi Picpoul Blanc

• 2023 Acquiesce Winery, Mokelumne River-Lodi Picpoul Blanc

• 2023 Bokisch Vineyards, Terra Alta Vineyard, Clements Hills-Lodi Albariño

• 2024 Klinker Brick Winery, Mokelumne River-Lodi Albariño

• 2023 Klinker Brick Winery, Lodi Grenache Blanc

• 2023 Bokisch Vineyards, Vista Luna Vineyard, Borden Ranch-Lodi Garnacha Blanca

• 2023 Perlegos Family Wine Co., Thera Block, Clements Hills-Lodi Assyrtiko

• 2022 Sabelli-Frisch, "Bund" Mokelumne River-Lodi Riesling

• 2023 Haarmeyer Wine Cellars, Cresci Vineyard, Borden Ranch-Lodi Chenin Blanc

• 2023 Monte Rio Cellars, Mokelumne River-Lodi French Colombard

• 2022 Mio Vigneto, Clements Hills-Lodi Ribolla Gialla

• 2024 Christopher Cellars, Mokelumne Glen Vineyard, Mokelumne River-Lodi Grüner Veltliner

• 2024 LangeTwins Family, North River Vineyard, Mokelumne River-Lodi Grüner Veltliner

• 2023 Markus Wine Co., Mokelumne River-Lodi Grüner Veltliner

• 2022 Harney Lane Vineyards, Scottsdale Vineyard, Mokelumne River-Lodi Chardonnay

• 2019 The Lucas Winery, Lodi Chardonnay

• 2023 Acquiesce Winery, Mokelumne River-Lodi Viognier

• 2022 Acquiesce Winery, Mokelumne River-Lodi Belle Blanc (Roussanne, Grenache blanc, Bouboulenc)

• 2023 Acquiesce Winery, Mokelumne River-Lodi Ingénue (Clairette blanche, Grenache blanc, Bouboulenc, Piquepoul)

• 2023 Haarmeyer Wine Cellars, Mokelumne Glen Vineyard, Lodi Victor Weisser, Gemischter Satz (52 German and Austrian grapes)

Harvesting of Flame Tokay, an heirloom variety utterly unique to Lodi, in a vineyard over 130 years old.

• 2024 Marchelle Wines, Mokelumne River-Lodi Old Vine Carignan Rosé

• 2023 Acquiesce Winery, Mokelumne River-Lodi Grenache Rosé

• 2023 LangeTwins Family Vineyards, River Ranch Vineyard, Jahant-Lodi Aglianco Rosé

• 2022 Sabelli-Frisch, Somers Vineyard, "Milk Fed 9" Mokelumne River-Lodi Mission Rosé

• 2024 Monte Rio Cellars, Heirloom Ranch, Mokelumne River-Lodi Flame Tokay

• 2023 Lorenza Wine, Lodi Rosé (Carignan, Grenache, Cinsaut, Mourvèdre)

Rows of own-rooted old vine Mokelumne River-Lodi Carignan in late March afternoon.

• 2024 Monte Rio Cellars, Somers Vineyard, Mokelumne River-Lodi Mission

• 2020 Sabelli-Frisch, Somers Vineyard, “Marina” Mission

• 2022 Perlegos Family Wine Co., Sprague Family Vineyard, Clements Hills-Lodi Cinsaut

• 2022 Christopher Cellars, Sprague Family Vineyard, Clements Hills-Lodi Cinsaut

• 2023 Rippey Family Vineyards, Abba Vineyard, Mokelumne River-Lodi Grenache

• 2021 Bokisch Vineyards, Terra Alta Vineyard, Clements Hills-Lodi Garnacha

• 2023 Haarmeyer Wine Cellars, Mokelumne Glen Vineyard, "Blau-Blau" Blaufränkisch

• 2020 PRIE Winery, Mokelumne River-Lodi Dornfelder

• 2023 Terah, River’s Edge Vineyard, Mokelumne River-Lodi Sangiovese

• 2022 Monte Rio Cellars, River’s Edge Vineyard, Mokelumne River-Lodi Sangiiovese

• 2021 Avivo, River’s Edge Vineyard, Mokelumne River-Lodi Red Wine (Sangiovese)

• 2021 Mettler Family Vineyards, Mokelumne River-Lodi Aglianico

• 2022 Haarmeyer Wine Cellars, Potrero Vineyard, Clements Hills-Lodi Nebbiolo

• 2022 Perlegos Family, Fernow Ranch, Mokelumne River-Lodi Nero d’Avola

• 2022 Christopher Cellars, Lodi Nero d’Avola

• 2021 LangeTwins Family, Redtail Vineyard, Jahant-Lodi Nero d’Avola

• 2022 PRIE Winery, Mokelumne River-Lodi Prieto Picudo

• 2021 PRIE Winery, Mokelumne River-Lodi Counoise

Craig Haarmeyer—a poster child for contemporary, low intervention style wines—during Borden Ranch-Lodi Chenin blanc harvest.

• 2023 Perch Wine Co., Viñedos Aurora Vineyard, Clements Hills-Lodi Petite Sirah

• 2022 Stonum Vineyards, XII Estate, Mokelumne River-Lodi Zinfandel

• 2022 St. Amant Winery, Mohr-Fry Ranch, Alicante Bouschet

• 2022 Mettler Family Vineyards, Mokelumne River-Lodi Pinotage

• 2022 Pax Winery, The Bench Vineyard, Clements Hills-Lodi Syrah

• 2021 Michael David Winery, Rapture, Lodi Cabernet Sauvignon

• 2017 Peltier Winery, Schatz Family Estate Reserve, Clements Hills-Lodi Cabernet Sauvignon

• 2020 Bokisch Vineyards, Terra Alta Vineyard, Clements Hills-Lodi Graciano

• 2021 Anaya Vineyards, Potrero Vineyard, Clements Hills-Lodi Semi-Carbonic Tempranillo

• 2021 Bokisch Vineyards, Liberty Oaks Vineyard, Jahant-Lodi Tempranillo

• 2018 Bokisch Vineyards, Lodi Gran Reserva Tempranillo

• 2021 Harney Lane Vineyards, Henry Ranch, Mokelumne River-Lodi Tempranillo

• 2023 Monte Rio Cellars, “Silva” Alta Mesa-Lodi Mencía

• 2021 PRIE Winery, Mokelumne River-Lodi Mencía

• 2021 Markus Wine Co. Lodi “Sol” (Petite Sirah, Petit Verdot, Syrah)

• 2021 Monte Rio Cellars, Teresi Vineyard, Mokelumne River-Lodi Red (Zinfandel/Petite Sirah)

• 2022 Christopher Cellars, Lodi “Grand Cuvée” (Carignan, Zinfandel, Cinsaut)

• 2023 Acquiesce Winery, “Christina’s Outlier” Mokelumne River-Lodi Red wine (Grenache, Syrah Mourvèdre, Bourboulenc, Clairette blanche)

• 2022 Perlegos Family Wine Co., Lodi Red Wine (Merlot, Cinsaut, Carignan)

• 2022 Perlegos Family Wine Co., “Duetto” Lodi Red Wine (Zinfandel, Nero d’Avola)

Nebbiolo picker in Lodi's Clements Hills AVA.

• 2022 St. Amant Winery, Jahant-Lodi Barbera

• 2023 Turley Wine Cellars, Bechthold Vineyard, Mokelumne River-Lodi Cinsaut

• 2023 Lorenza Wine, Bechthold Vineyard, Mokelumne River-Lodi Cinsaut (Bechthold Vineyard)

• 2022 Sandlands Wine, Lodi Cinsaut (Bechthold Vineyard)

• 2020 Marchelle Wines, Bechthold Vineyard, Mokelumne River-Lodi Cinsaut

• 2022 Fields Family, Bechthold Vineyard, Mokelumne River-Lodi Cinsaut

• 2022 Kareen Wine, Bechthold Vineyard, Mokelumne River-Lodi Cinsaut

• 2022 Michael David Winery, Bechthold Vineyard, Mokelumne River-Lodi Cinsaut

• 2022 Sandlands Wine, Mokelumne River-Lodi Carignan (Spenker Ranch)

• 2022 Precedent Wine, Spenker Ranch, Mokelumne River-Lodi Carignan

• 2022 Christopher Cellars, Mule Plane Vineyard, Mokelumne River-Lodi Carignan

• 2023 Perlegos Family Wine Co., KMS Collection-Mule Plane Vineyard, Mokelumne River-Lodi Carignan

• 2020 Stonum Vineyards, Mule Plane Vineyard, “Unbroken” Mokelumne River-Lodi Carignan

• 2021 Markus Wine Co., Nicolini Ranch, Mokelumne River-Lodi Ancient Blocks Carignan

• 2022 Monte Rio Cellars, Jessie's Grove Vineyard, Mokelumne River-Lodi Carignan

• 2020 Marchelle Wines, 1900 Block-Jessie’s Grove, Mokelumne River-Lodi Carignan

• 2021 Marchelle Wines, Mokelumne River-Lodi Family Cuvée (Zinfandel, Carignan, Mission, Black Prince)

• 2022 Sandlands Wine, Lodi Red Table Wine (Cinsaut, Carignan, Zinfandel)

• 2022 Perch Wine Co., Lodi Kestrel Red (Carignan/Zinfandel/Cinsaut/Petite Sirah)

• 2021 Markus Wine Co., The Church Block, Mokelumne River-Lodi Ancient Blocks (Carignan, Petite Sirah, Alicante Bouschet)

Broken armed Zinfandel in Clements Hills-Lodi's Dogtown Vineyard, since the late 1990s bottled as a vineyard-designate wine and one of the first to be crafted in a minimal intervention, terroir focused style.

• 2022 Turley Wine Cellars, Dogtown Vineyard, Clements Hills-Lodi Zinfandel

• 2023 Haarmeyer Wine Cellars, Stampede Vineyard, Clements Hills-Lodi Zinfandel

• 2023 Perlegos Family Wine Co., Stampede Vineyard, Clements Hills-Lodi Zinfandel

• 2023 Christopher Cellars, Stampede Vineyard, Clements Hills-Lodi Whole Cluster Zinfandel

• 2023 Christopher Cellars, Stampede Vineyard, Clements Hills-Lodi Whole Berry Zinfandel

• 2022 Maître de Chai, Stampede Vineyard, Clements Hills-Lodi Zinfandel

• 2022 Little Trouble Wine Co., Stampede Vineyard, Clements Hills-Lodi Heritage Red Blend (Zinfandel, Mission, Alicante Bouschet, Syrah, Grenache, Flame Tokay)

• 2022 St. Amant Winery, Marian's Vineyard, Mokelumne River-Lodi Reserve Zinfandel

• 2021 St. Amant Winery, Mohr-Fry Ranch, Mokelumne River-Lodi Zinfandel

• 2021 Harney Lane Vineyards, Lizzy James Vineyard, Mokelumne River-Lodi Zinfandel

• 2021 Harney Lane Vineyards, Scottsdale Vineyard, Mokelumne River-Lodi Zinfandel

• 2020 Mettler Family Vineyards, HGM Ranch, Mokelumne River-Lodi Zinfandel

• 2022 Monte Rio Cellars, Faith Vineyard, Mokelumne River-Lodi Zinfandel

• 2022 Jessie’s Grove, Royal Tee Vineyard, Mokelumne River-Lodi Zinfandel

• 2021 Monte Rio Cellars, Royal T Vineyard, Mokelumne River-Lodi Zinfandel

• 2023 Sabelli-Frisch, “inedal” Jacob’s Two Acres Vineyard, Mokelumne River-Lodi Zinfandel

• 2021 LangeTwins Family, Starr Vineyard, Mokelumne River-Lodi Zinfandel

• 2022 Turley Wine Cellars, Steacy Ranch, Mokelumne River-Lodi Zinfandel

• 2022 Sandlands, Mokelumne River-Lodi Zinfandel (Kirschenmann Vineyard)

• 2022 Turley Wine Cellars, Kirschenmann Vineyard, Mokelumne River-Lodi Zinfandel

• 2021 Precedent Wine, Kirschenmann Vineyard, Mokelumne River-Lodi Zinfandel

• 2023 Bedrock Wine Co., Katushas’ Vineyard, Mokelumne River-Lodi Zinfandel

• 2023 Klinker Brick Winery, Marisa Vineyard, “Echoes” Mokelumne River-Lodi Zinfandel

• 2018 The Lucas Winery, ZinStar Vineyard, Mokelumne River-Lodi Zinfandel

• 2023 Iconic Wine, Schmiedt Vineyard, “Old Gods” Mokelumne River-Lodi Zinfandel

Biodynamic grown Sangiovese in Mokelumne River-Lodi's River's Edge Vineyard.

Effervescence of Lodi

• 2023 Perlegos Family Wine, Clements Hills-Lodi Sparkling Assyrtiko

• 2021 Markus Wine Co., Mokelumne River-Lodi Sparkling Bacchus

• 2021 Acquiesce Winery, Mokelumne River-Lodi Sparkling Picpoul Blanc

• 2022 Acquiesce Winery, Mokelumne River-Lodi Sparkling Clairette Blanche

• 2021 Acquiesce Winery, Mokelumne River-Lodi Sparkling Grenache Rosé

• NV Klinker Brick Winery, “Bricks & Roses” Lodi Sparkling Brut Rosé (Grenache, Carignan)

Assyrtiko harvest in Perlegos Family's Thera Block, in Lodi's Clements Hills appellation.