Letters from Lodi

An insightful and objective look at viticulture and winemaking from the Lodi

Appellation and the growers and vintners behind these crafts. Told from the

perspective of multi-award winning wine journalist, Randy Caparoso.

How global warming is changing winegrowing in Lodi and the rest of the world

Lodi in the third week of July 2024: Old vine Zinfandel veraison (i.e., annual change of colors) looking good, but slowed down by two heat dome events, repercussions of now well documented climate change.

Climate change's global impact and near-future projections

Never mind the squabble over the causes. Vintners all over the world are now living with climate change, manifested as warming of temperatures on a global scale.

The question is, how is the wine industry adjusting to this phenomenon? In France's Bordeaux region, a centuries-old bastion of wine tradition, authorities have recently authorized the planting of six "new" grapes: Albariño, Liliorila (a cross of Chardonnay and Baroque), Touriga Nacional, Castets, Marselan (Grenache x Cabernet Sauvignon cross), and Arinarnoa (Tannat x Cabernet Sauvignon).

Meanwhile, the University of Bordeaux, according to undark.org, has been cultivating a "living database of 52 wine grape varieties" for the express purpose of researching "new varieties to adapt to new temperatures.” Some Bordeaux vignerons are not waiting for government approval and have already begun experimenting with more heat-tolerant grapes such as Grenache, Syrah, Carignan, Nero d'Avola and Tempranillo (in appellations such as Bordeaux where grape varieties are regulated by law, vintners may produce wines from unapproved grapes but they may not be used in bottlings labeled as "Bordeaux").

Lodi's Jeff Perlegos, owner/grower of Perlegos Family Wine Co., discussing climate change strategies among his old vine Zinfandel.

That's Bordeaux, what about Lodi?

First, some definition: Since the 1950s, most of the wine world has used a climate classification system called Köppen–Geiger (originally devised in 1884 by a German-Russian climatologist named Wladimir Köppen). In this system, regions such as the Lodi Viticultural Area are classified as Csa, which is defined as a Hot-summer Mediterranean climate (re Mediteranean climate). By comparison, parts of Napa Valley and Sonoma County are also classified as having a Csa climate, while other parts of Napa Valley and a bigger chunk of Sonoma County are classified as Csb, or Warm-summer Mediterranean climate. In layman's terms, Csb is considered a slightly cooler climate than Csa.

Earlier this year, a team of climatologists led by Oregon's Gregory V. Jones have published a revision of the Köppen-Geiger classifications entitled Historic Changes and Future Projections In Köppen-Geiger Climate Classifications in Major Wine Regions Worldwide. Its purpose, as you might surmise, is to give a better accounting of the rising temperatures taking place over the past 50 years, as well as to make some science-based, hard-nosed projections of what wine regions all around the world should expect over the next 20 to 40 years.

Gregory V. Jones in his home vineyard in Southern Oregon. Abacela Vineyards.

Two years ago Professor Jones wrote to me, clarifying what he and his researchers had already found, particularly about C Temperature climate zones defining Lodi and other regions up and down the California coast. Wrote Jones: "Using the updated Köppen-Geiger gridded data, we have found that the midlatitude C climates make up roughly 55 percent of the world’s defined wine growing regions. However, Mediterranean climate types (Csa, Csb) only make up roughly 15 percent of the surface area of wine regions globally."

In short, according to Jones, Csa and Csb climate zones of the sort found in Lodi and much of California are far less extensive on a global scale than commonly thought.

According to Jones' latest research, however, global warming has literally been changing the writing on the wall. It's coming hard and fast. Lifting passages directly from the paper:

Recent research has shown that climate change is already affecting viticulture and wine production through changes in grapevine phenological development, harvest dates, and grape acidity and sugar content. However, establishing relationships between environmental changes and other components, like polyphenols or aroma compounds, is more complex. This research has added to the baseline knowledge of the potential changes of climate on viticulture and wine production by examining global and regional-scale shifts in the KG climate types for wine regions.

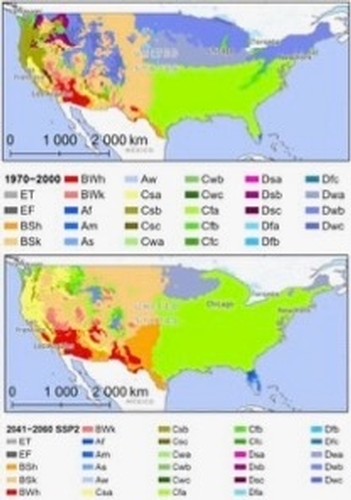

Findings from the most recent Köppen-Geiger climate classification research showing American climate zones from 1970-2000 (top) compared to projections for 2041-2060 (bottom). Note the projected decrease of Csb regions and expansion of yellow Csa regions (translation: in 20 years, most of California will have the same Mediterranean climate classification as Lodi).

The main climatic shifts identified in this study are: Regions shifting to a warmer and drier climate (temperate warm-summer Mediterranean (Csb) to temperate hot-summer Mediterranean (Csa); dry semi-arid cold (BSk) to dry semi-arid hot (BSh) and arid hot desert (BWh) climates); and (2) other regions shifting to a warmer and moister climate (temperate oceanic (Cfb) to humid subtropical (Cfa)).

At the cool limits of viticulture, warming and shifting to more suitable climate types identified in this research will likely increase the potential ripening of the main varieties being grown today and expand the range to other varieties.

Wine regions of the west coast of the USA are mostly projected to transition from a temperate warm-summer Mediterranean (Csb) to a temperate hot-summer Mediterranean (Csa) climate type, like what is projected in the IP, while in California, dry arid hot climate types (BWh-desert) are expected to increase, reflecting that the summers are expected to be much hotter.

Trellised Zinfandel in KG Vineyard Management's Kolber Ranch, on the Delta side of the Lodi appellation.

In other words, according to Jones and his team, present-day "cooler" climate regions such as much of the Sonoma Coast and the Central Coast (from Santa Barbara to Monterey) are all projected to transition to Csa (i.e., Hot-summer Mediterranean climate), similar to Lodi's. This will happen by 2041, less than 20 years from now. As Jones underlines:

Significant shifts in the most recognizable wine region climate type, Mediterranean, is likely to occur with projections showing that temperate warm-summer Mediterranean climate (Csb) areas decline from over 9% to close to 1%, while temperate hot-summer Mediterranean climate (Csa) areas increase from around 10% to just over 17% from the recent past to mid-century.

Ready or not, according to these studies, global warming is already kicking down our doors.

How Lodi growers and vintners are adjusting to climate change

Although the climate in Lodi is projected to remain pretty much the same over the next 20 to 30 years⏤at least in terms of its Csa Köppen-Geiger classification⏤most of Lodi's own growers and vintners have not only been planning for climate change, they have already begun taking active measure to counteract some of the repercussions, particularly as they pertain to changing weather events.

Jeff Perlegos this past week, demonstrating one of his farming techniques for mitigating high temperatures: Pulling of leaves around the fruit zone on the north side of his old vines to trigger ripening response.

Says Jeff Perlegos, a grape grower as well as co-proprietor of the Perlegos Family Wine Wine Co. brand:

We used to have lots of fog throughout the winter, which didn't burn off for a few weeks. That's all gone. We now have warm winters, which hasten bud break, which pushes the vines to ripen earlier [July-August] when we can still have intense heat vs. ripening in mid-late September when when weather is milder.

In the past five years I have noticed more sustained days over 100° vs. prior. This year we are obviously experiencing an extended heat dome effect. The weather is clearly more variable than it ever was in years prior.

Climate change has already changed some of their farming practices, according to Perlegos, who adds:

In warm winters we try to delay pruning to as late as feasible in hopes of delaying bud break. We want to avoid frost issues, of course, but also hope to delay sugar ripening until after we get past the bulk of the heat which can last even up to Labor Day [first Monday in September]. Additionally we want to build organic matter in the soil so we it can aid in sequestering as much water in the soil as possible.

We incorporate our cover crop in most years. We are also mindful of leaf layers on the shoots between sunlight and fruit. We aim for speckled, dappled sunlight to hit the grapes especially in the cooler mornings. We remove leaves to let sun (and air for mildew) into the canopy but limit direct sunlight that would last for hours as much as is feasible.

Aggressive spring cover crop in the Acquiesce estate, recently increased in response to climate change concerns; rather than mowed or tilled, growth between rows is now crimped (stems snapped and plants flattened) to help keep ground temperature low. Acquiesce Winery.

Christina Lopez, the winemaker and vineyard manager of Lodi's Acquiesce Winery estate, tells us that she has been thinking long and hard about climate change. According to Lopez:

It’s undeniable that we’re getting more extreme weather more frequently. Plants rely on cues from the environment and respond accordingly, whether it be stress or transitioning through phenological stages. So, the question becomes, how do we better prep our vineyards to take on an unpredictable future? This was the major factor in our recent decision to take a more regenerative approach to soil health.

Our first step has been to build up our soils organic matter by utilizing cover crops. There are many benefits even at small increments such as increased water holding capacity, infiltration, and biodiversity. Water is our most precious resource, so if we can optimize our usage that’s a huge win. The trick is you have to keep roots in the ground for as long as possible.

This past year we began crimping to create a mulch carpet as opposed to mowing or tilling the cover crop in. We are seeing incredible results in soil temperature with this technique that will allow our soils to function better in prolonged heat, as high as a 40-degree difference between bare and covered soil on a triple digit day. The ultimate goal is to build resiliency into our vineyard to combat whatever is thrown our way.

Acquiesce winemaker/vineyard manager Christina Lopez.

This past week, Markus Niggli of Markus Wine Co. took a few minutes during his vacation in Cancún to share a few thoughts on how climate change has been impacting grapevine growth even as we speak, in 2024:

What has changed in the past few months has been the longer periods of 100-degree days, which started so much earlier than before. We did open up the [grapevine leaf] canopy in our old vines in Church Block and Nicolini Ranch just after flowering. I expected things to move fast with the hotter days but they didn’t. As of July 22, we were currently at about 20%, 25% veraison [i.e., shift in color of red wine grapes from green to black] in the old vine blocks. The plants have been closing down production to protect themselves from the heat. I have almost no sunburn, though, and berry size is normal.

Markus Wine Co.'s Markus Niggli pruning Lodi old vines.

Although, says Madelyn Ripken Kolber⏤a sustainability wonk who operates KG Vineyard Management with her husband Ben Kolber⏤there is "nothing predictable" about winegrowing, "We have been doing the best we can to adapt and respond to the challenges of climate change." According to Kolber:

We are seeing a trend towards more extreme heat and need to take into consideration how this affects our farming plans. First and foremost, we need to keep our labor force safe. Due to the triple digit heat, we have had to adjust employees' shifts and reduce hours. This means sending crews home early when we reach a certain temperature. Cutting shifts short is a challenge for the employees, who depend on their income to provide for their families, as well as a challenge for the management team trying to plan how to complete the necessary work in the fields.

KG Vineyard Management's Madelyin Ripken Kolber (left) leading a sustainable farming seminar in Lodi's Kolber Ranch.

We are also mindful of our canopy management to provide a balanced amount of leaf coverage to stay ahead of scorching heat spells, like we saw in 2022 so close to harvest.

Attention to best practices in soil management is important too. Keeping permanent cover crops between rows that are mowed has allowed for lower temperatures on the soil. Carbon capture is a hot topic, and repeated discing throughout the year does not benefit our efforts to capture carbon.

Lastly, we are always working on staying efficient with our resources, such as reducing field passes and recycling materials. Especially during tough times for wine sales, reducing vineyard costs is a huge priority while maintaining high quality fruit.

As Professor Jones warns, "These shifts [in climate] are a further indication of the need tor adaptive measures in the wine sector to address potential challenges to grape cultivation and wine production in the future"⏤and Lodi winegrowers are accepting that challenge.

Church Block, a Historic Vineyard Society-certified old vine Lodi block managed by Markus Wine Co.'s Markus Niggli.