Letters from Lodi

An insightful and objective look at viticulture and winemaking from the Lodi

Appellation and the growers and vintners behind these crafts. Told from the

perspective of multi-award winning wine journalist, Randy Caparoso.

Knowing, enjoying wine 101

Is this wine lover having too much fun? Discuss...

De plan, de plan…

Over the next few weeks we plan to devote one blogpost per week covering some basic aspects of wine, from how vineyards effect quality and style to, simply, how to taste wine and enhance its enjoyment. Yes, we’re talking “basics,” but we promise: we’re not going to dumb it down for you. We figure that if you’re reading this, you’re probably a curious wine lover, and you want something of substance along with some A, B, Cs. Why not? To begin with…

What makes wine wine?

Oh lord, Lodi grown white Vitis vinifera...

If left to its own devices, any batch of grapes that is smashed or “crushed” into a container, will start to turn itself into the adult beverage we all know and love as wine. It is yeast flora, naturally growing on the skins of grapes, that become activated when coming in contact with the sugar in grapes. The result is liquid manna (so to speak) containing as little as 8% or 10% or up to 14% to 16% alcohol; after which yeast cells either run out of sugar to convert (resulting in a “dry” wine) or else simply die off from the inability to live at higher alcohol levels.

Therefore, where man, and artistry, enters the picture is in the selection of grape type, where and how the vine is cultivated, and what is done once the grapes are picked, fermented and (if at all) aged in a barrel or tank before being bottled and sold.

We know, for instance, that grapes originating from the European family of grapes called Vitis vinifera make finer tasting wines than those made from varieties of native American grapes, such as Vitis labrusca. Chardonnay, Riesling, Merlot, Cabernet Sauvignon and Zinfandel are all examples of vinifera that are common in the lexicon of today’s wine lovers (or in the annoying chatter of wine geeks).

However, unlike native American vines, vinifera is highly susceptible to the root eating louse called phylloxera, a pesky, little bug that once decimated most of the vineyards in Europe (sacré bleu!) and California (what the hey…) at the end of the nineteenth century. Therefore, most of the fine wine vineyards in Europe and California are now grafted on to variations of phylloxera-resistant rootstocks derived from labrusca varieties. Guess those American vines are good for something after all.

What makes winemakers whine?

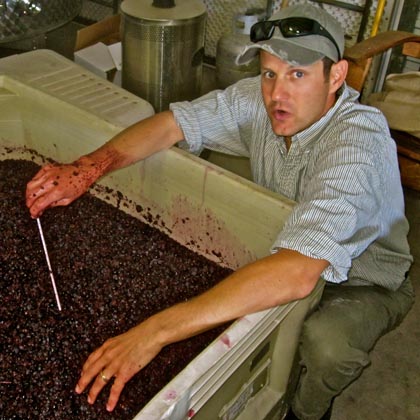

Lodi winemaker Chad Joseph, praying for good zin...

Although the wine growing and production industry around the world is driven by knowledge of how best to do things based upon centuries of trial-and-error, Mother Nature still has her say in things. For instance, early spring frosts, torrentials, mildew, or even hailstorms during the period when vines are flowering — which establishes the number of berries ending up in each grape cluster — has a direct impact on whether or not a vineyard produces half as many grapes as years before, or a good percentage more.

Earlier in the month we spoke to one producer of prestige quality Lodi Zinfandels, who just got through evaluating the progress of two of his old vine vineyards at this point in the 2011 season. Walking through the vines, he could clearly see that bunch sizes as well as individual berry counts were a third to half of what they got last year. If they had felt that last year’s crop load was too big to achieve their quality objectives – forcing them to drop fruit to the ground some time during the summer – Mother Nature just might have done them a favor. But the fact is, this wasn’t the case in 2010, and so in 2011 they’re expecting 40% less than what they want, and now they’re scrambling to find more vineyards to draw from. No doubt (given the track record of their vineyards), what they’ll end up with is great tasting Zinfandel. Just that much less. When Mother Nature says jump, sit, or kneel and pray, you jump, sit… and start to pray.

Nature often allows growers to harvest a decent quantity of grapes, but she throws wicked curves by sending heavy rains in October that dilute the quality of nearly ripened grapes, or heat waves in August that shrivel up the grapes before they have a chance to ripen into optimal flavors. Translated into economics: Nature’s grip on quality definitely determines if a winery can produce batches of special, ultra-premium quality wine for $25, $55, $75 a bottle or more, or if the entire vintage needs to be downgraded into more average quality $14, $16 wine, or — if the vintner is thoroughly disgusted — sold off as fermented juice for cheap on the bulk market, ending up with bigger wineries producing anonymously sourced two-bucks or wines in-a-box.

Bottom line: no matter how much knowledge, experience, high tech growing or fermentation tools a wine producer may have at his disposal, wine is still very much an agricultural product. Both quantity and quality begin and end with what can be grown in a vineyard, not conjured up in a winery.

Next 101: The color and basic taste sensations of wine

While miraculous 100 year old zin vines like this one on Lodi’s eastside are still productive, many of them are producing fewer clusters, with fewer berries, in 2011.