Letters from Lodi

An insightful and objective look at viticulture and winemaking from the Lodi

Appellation and the growers and vintners behind these crafts. Told from the

perspective of multi-award winning wine journalist, Randy Caparoso.

Everything you need to know about the acidity of Lodi's extraordinary range of varietals

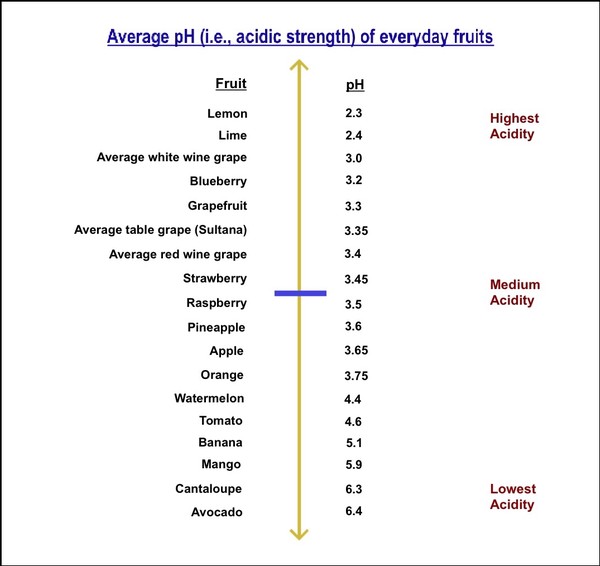

When wine lovers talk about acidity in wine, they are not talking about anything mysterious or highfalutin. If you're a human being who eats what most people eat, you already understand acidity. Almost everyone knows, for instance, lemons and limes are very tart in terms of acid content. Therefore you do not bite into lemons and limes the same way that you readily eat a mango or cantaloupe, which have an opposite amount of acidity—very soft, lush, juicy.

There is, of course, an enormous variety of wines, just like there are endless varieties of fruit. Most New World wines—that is, wines grown and produced in regions such as the U.S., Australia, New Zealand and anywhere in South America—are sold primarily as "varietal" wines; that is, by the names of grapes from which the wines are primarily made. And, as in anywhere around the world, the vast majority of commercial wines are either white, red, pink (i.e., rosés) or sparkling (the latter, wines popularly called champagne).

No sense wasting.

All wine consumers quickly become acquainted with the levels of acidity in most wines. They know, for instance, that champagnes and white wines tend to have a perceptible amount of acidity or tartness in their taste (Art Buchwald once said acid-sharp champagne tastes "like my foot is asleep"). Without acidity, champagnes and whites taste dull or flat, and no one really cares for dull, flat bottlings of these wine types.

It is the same with rosés—you expect pink wines to be mildly tart, because without at least a modest or perceptible amount of acidity most rosés come across as dull or flat.

Red wines, on the other hand, are generally lower in acidity than whites or rosés. That is to say, the vast majority of reds are do not have an outwardly tart taste, with a few exceptions. The exceptions include red wines made from grapes such as Barbera, Sangiovese or Zinfandel which can be slightly zesty because they are made from black skinned grapes that are naturally a little higher in acidity than reds made from grapes such as Merlot or Cabernet Sauvignon.

If, of course, you have yet to taste a Zinfandel or Merlot, then you wouldn't necessarily know the differences. I cannot, for instance, describe the heady feeling of standing atop a 10,000-ft. mountain, or how your feet feel as foamy waves slide up along the sand between your toes. You have to go to a mountain or to an ocean beach to understand that. But once you do, you start to have expectations, same way as after you've experienced a few different wines: When you buy a bottle of Zinfandel, that is to say, you naturally expect a slightly zesty red wine, a little different from the taste of a Merlot, which is usually softer, rounder and usually less zesty in your mouth.

There is no mystery about anything that is learned from experience. We usually learn about the acidity of wines many years after we learn about foods because it is an adult beverage. But it is no different from knowing, when you add a squeeze of lemon to a plate of fish or oysters, the dish is probably going to taste better because you're adding a tart, sharp flavor that naturally enhances fish or oysters.

Caesar salad ingredients: romaine, lemon, parmesan, anchovy, olive oil, Worcestershire, garlic, mustard and yolk of coddled egg.

Or when you make a dressing for your salad, which is an act of balancing the acidic taste of vinegar with the round, soft taste of an oil, judging the proportions according to personal taste. If you prefer your leafy greens to taste fresh and zesty, you might not want to add any oil at all—you simply drizzle a good balsamic or sherry vinegar on your salad and let it go at that. Perhaps you love the taste of pure olive oil; so you drizzle your favorite brand of olive oil on your greens without any vinegar—maybe just salt, pepper and a squeeze of lemon (classic Caesar salad dressing, for instance, contains no vinegar, just lemon juice, plus other good stuff like high umami parmesan and anchovy). When it comes to taste, it's always a matter of live-and-learn.

In any case, what is plain as day is the fact that acids are a natural component of all fruits, including grapes, from which wines are made. Because of that, all wines have a range of tastes related to acid levels intrinsic in the grapes they are made from. Although when you talk about acid levels in wines, you don't usually say "acidity"— you use more relatable terms such as fresh, tart, sour, lively, zesty, or (when acidity seems extra high) sharp, steely or edgy. Lower acid wines are often described as soft, round, plump or easy.

Vineyards in France's Picpoul de Pinet planted to the lemony tart Piquepoul grape: Not coincidentally, spilling into a basin inundated with oyster beds, producing the fruits de mers (i.e., varieties of briny shellfish) complmented by the white wines of the appellation.

Many people prefer their wines to be soft and fruity, often a little sweet and with no sharp acidity at all. Others can't stand fruitiness, and have a preference for wines that are downright tart, super-dry or pointedly sharp. Making things even more interesting, higher acid wines—especially those of Europe (although not unheard of in New York, California or Oregon)—often have non-fruit attributes suggesting some kind of minerality. Not surprisingly, whatever your taste in wine, the presence of acidity also tends to brighten aromatic qualities of all wines, dry or sweet, and often with refreshing suggestions of citrusy fruit.

Now that you are cognizant of this, are you ready to geek out a little more? Let's start with this little bit of science: Acidity in grapes as well as in finished wines is technically measured in terms of titratable acidity (identified as "TA," or the sum of all the organic acids in juice or wine), although the actual strength of acidity is measured in terms of pH.

You do not need a degree in chemistry to understand pH; only the fact that the lower the pH in a wine, the higher the taste of acidity. Understanding pH is no different from understanding levels of acidity in the foods we eat every day. Ergo, the following chart, which lists the average pH of many of the everyday fruits in our diet, from the those with lowest pH (such as lemons and limes) to the highest pH fruits (lower acid cantaloupes and avocadoes):

I'm also sharing this chart so that you understand one of the basic aspects of wines: That white wines are generally made from grapes with higher acidity than grapes that go into red wines. Therefore, white wines are often a little tart and more perceptively zesty, whereas red wines tend to be rounder or softer in acidity.

While less outwardly tart, most red wines tend to be sturdier than whites and rosés because they are fermented with the skins and seeds of grapes, which impart both color and tannins; the latter components being the phenolic compounds that add drying, meatier or mouth-filling sensations. The vast majority of white wines, on the other hand, are lighter in feel because they are fermented from grapes after their juice is completely separated from their skins. Therefore, unlike red wines, the taste of tannin is not a major factor in most white wines. Instead, most white wines are appreciated for their levels of zestiness in terms of acidity.

Tuscan style beef ("bistecca alla fiorentina"), typically served with wedges of lemon and served with Tuscan red wines made from Sangiovese, one of the world's higher acid black skinned grapes. Getty Images.

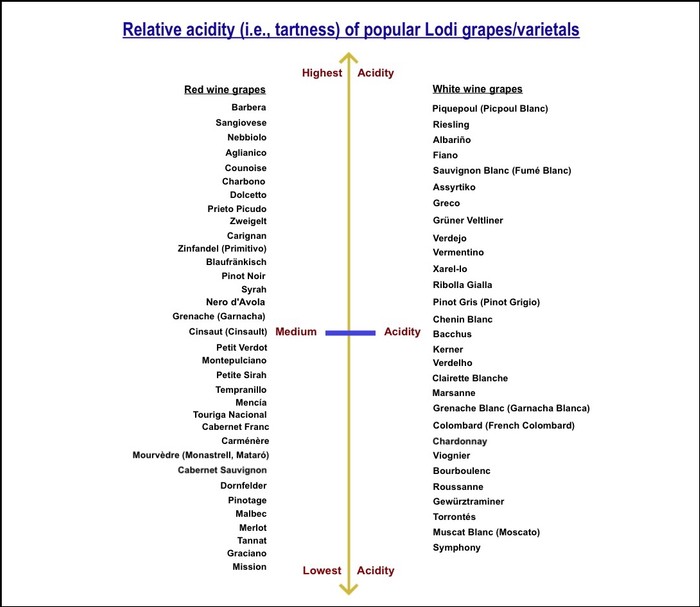

Also as previously mentioned, once you you start to become familiar with different wines you soon learn which wines, based upon the grapes from which they are made, tend to be higher in acidity, lower in acidity, or somewhere in between.

This knowledge becomes especially handy when it comes to choosing ideal wines for different foods. When you know, for instance, which white wine varieties are a little higher in acidity, you can make better choices for foods that are naturally complimented by citrusy or even sharply balanced whites: Such as salads in vinegary dressings, seviches, most fish or shellfish.

At Lodi Farmers Market, fresh tomatoes—a moderately acidic ingredient that makes a natural match with moderately acidic red wines such as Zinfandel and Sangiovese based blends.

It is the same for red wines: Pasta in zesty tomato sauces, for example, invariably taste better with red wines made from higher acid black skinned grapes because of the moderate acidity in tomatoes, which in school they teach you is actually a fruit, not a vegetable. Grilled steaks, on the other hand, are fantastic with red wines that are lower in acidity but sturdier in tannin or even the smoky taste of oak barrels (full bodied reds are traditionally aged in wood to round out high tannin levels).

That said, here is a handy guide to most of the different kinds of wines grown in the Lodi appellation, broken down by grape variety and their average levels of acidity, from highest to lowest:

The skinny: If you prefer white wines on the lemony tart side, you look for bottlings of Picpoul Blanc, Albariño, Fiano or Sauvignon Blanc. For the zestiest, mildly tart edged red wines, look for Barbera, Sangiovese, perhaps Aglianico or Zinfandel.

On the opposite end, rounder lower acid white wines would include Torrontés, Roussane, Viognier or Chardonnay; lower acid reds include Mission, Merlot, Dornfelder or Cabernet Sauvignon.

Medium acid whites—crisply balanced, not too tart, not too fat—include Pinot Gris (a.k.a., Pinot Grigio), Chenin Blanc, Kerner or Grenache Blanc. Medium acid reds—a little round, mildly zesty but not sharp or edgy—include varietals such as Syrah, Grenache, Petite Sirah and Tempranillo.

And once you know, you can enjoy all the different wines all the more!

Symphony grapes grown by Lodi's Ironstone Vineyards, producing lower acid yet soft, bright, lusciously fruited white wines.