Letters from Lodi

An insightful and objective look at viticulture and winemaking from the Lodi

Appellation and the growers and vintners behind these crafts. Told from the

perspective of multi-award winning wine journalist, Randy Caparoso.

The myths attached to wine regions and best climates for wine grapes

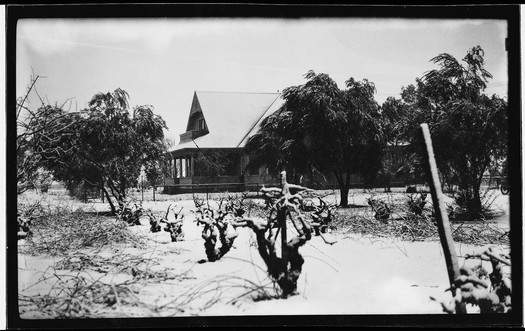

"Contemplation" among old vines at Lodi's The Lucas Winery estate.

The wine world has always been full of myths. Why? Because mystique and imagination play as big a role in the enjoyment of wines as facts and figures. Wine, after all, is often described as an art, and leaps of imagination are very much a part of all artistic endeavors.

As you would expect, almost all myths are eventually dispelled, at which point they become more like inconvenient truths—things that most people can't or won't accept, even if we know they're true. We love our myths, our unfounded superstitions, our compelling mystiques. We desperately cling to them because they bring order and predictability to our lives. Until they don't.

For example, when I first started in the industry during the late 1970s it was "common knowledge" that the finest wines in the world came from France, and that wines from the places such as California or Oregon were, at best, pale imitations. As many long time wine buffs now know, events such as the Judgement of Paris in 1976⏤when French judges famously rated California wines higher than American wines in a blind tasting⏤quickly put an end to that erroneous myth.

Whimsical depiction of the 1976 Judgement of Paris. Christopher Stewart Wine & Spirits.

The problem with the Judgement of Paris, though, is that it ended up creating even more myths, such as...

1. The finest wines of California are made from just two grapes, Cabernet Sauvignon for reds and Chardonnay for whites.

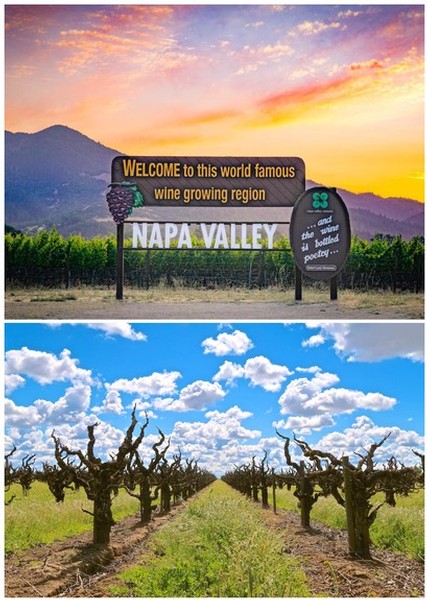

2. The finest wines in America come from Napa Valley.

3. Heck, all California wines come from Napa Valley, don't they?

This, of course, is not to grouse about the fact that Napa Valley does indeed make very good wine, or that California Chardonnays and Cabernet Sauvignons are first class⏤perhaps as good as any in the world.

Lodi grown Cabernet Sauvignon and Chardonnay, California's two most important wine grapes.

Still, facts are facts. Beginning with the fact that wines grown in Napa Valley add up to just 4% of all the wines grown in California (re Capstone California).

Logically, the reason there is another 96% of wine regions in California achieving success in the business of growing grapes and making wines is, simply, because their products are just as good, or better, than those of Napa Valley. Otherwise, they wouldn't be successful

Wine appreciation, however, is like the appreciation of anything involving personal taste, arts or crafts. We can all have good taste without having the same taste. Particularly when it comes to grape varieties. I rarely, for instance, drink Chardonnay at home, and Cabernet Sauvignon on just rare occasion. On a daily basis I drink mostly Zinfandel or Pinot Noir because, well, it's wine I find most aesthetically pleasing, especially with dinner. Therefore, it's wine I never tire of.

It is widely acknowledged that regions such as Santa Barbara and Sonoma County (not to mention Oregon's Willamette Valley) make very good Pinot Noir, whereas Cabernet Sauvignon has proven to be eminently suited to Napa Valley. Pinot Noir tends to be a little lighter, more fragrant and, many say, sexier in texture or feel than Cabernet Sauvignon.

Many American Pinot Noir fanatics would admit that even they didn't develop a taste for the varietal until after the movie Sideways came out. It was a good movie. A few cringe-worthy scenes, but it did make a heartfelt case for the appreciation of Pinot Noir, as opposed to Cabernet Sauvignon or that dreaded "other" wine, Merlot.

In any case, we now have a myth of Pinot Noir as being, perhaps, the sexiest varietal red around. Which, alas, leaves aficionados of other sexy reds, such as Grenache and Syrah, wondering, "Isn't Syrah and Grenache sexy enough?" Obviously, it's like saying brunettes are just as sexy as blondes, or Eilish compares to Swift, Stones beat Beatles, and so forth. Everybody's right, myths do not apply when it comes to any matters of taste. We happily create myths in our own minds.

The Napa Valley and Lodi Viticultural Areas: One being California's most famous wine region, the other the largest.

Then there is Zinfandel, California's most historical grape. Zinfandel is historical because of what happened after gold was discovered in in Sutter Creek in 1848. Brand new settlers from across the country and all around the world flocked to the West Coast to strike it rich, and California was ratified as a state faster than a scalded cat, more quickly than a politician changes his mind, and speedier than double-struck lightning or a knife fight in a phone booth. In other words, not fast enough.

Just as quickly, Zinfandel became the major grape of California for the simple reason that, of all the European wine grapes enterprising new settlers planted up and down the state, Zinfandel grew the easiest, yielded the most grapes and made the best wine. A proverbial no-brainer; even if, strangely enough, no one knew exactly where the grape originated (that information wouldn't become common knowledge until the 1990s, mostly likely because Zinfandel turned out to be native of Croatia, one of the "lesser" wine producing nations of Europe).

Mid-1800s photo of gold miners in Sutter Creek. suttercreek.org.

Zinfandel, however, is rarely counted among the finest wines of the world. Yet there are legions of consumers who are more apt to drink it every day. Over the past fifteen or so years local wineries, such as Michael David and Klinker Brick, have been reporting that Scandinavian countries (Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Finland et al.) have been among their biggest markets. They're drinking mostly Zinfandel.

If actual consumption was a measure of a wine's "greatness," Zinfandel would be right up there with best, close to the top.

Hence, you might have heard that Lodi grows more Zinfandel (about 40%) and has by far the largest acreage of "old vines" (i.e., pre-1970s plantings) in California. Why is that so? For pretty much the same reason why Zinfandel was preferred throughout California up until the 1960s: Because it grows so darned well and makes consistently good wine. Lodi's environment⏤or in wine lingo, its terroir⏤is more conducive to the grape than anywhere else.

Early 1800s illustration of Plains Miwok in the lush environment of their native San Joaquin Valley. The San Joaquin Historian, The Native Peoples of San Joaquin County.

Which brings up one of the American wine industry's biggest myth of all...

The myths attached to "hot climate" regions and wines

According to international climate classification systems such as Köppen-Geiger, Lodi falls into the "Csa" zone, defined as "Mediterranean⏤mild with dry, hot summers." Similar climatic zones, such as those of Napa Valley and Sonoma County, are classified as "Csb," or "Mediterranean⏤mild with cool, dry summers."

Honestly, when we describe Lodi's climate to scholars and wine buffs we tend to stick to the catch-all term "Mediterranean climate," referring to the weather as "warm and dry." We tend to avoid saying "hot" because of the way most people's minds work. When you say "hot," even the most intelligent people tend to think of the Gobi Desert, Death Valley or Arizona's Valley of the Sun. Lodi is not that hot.

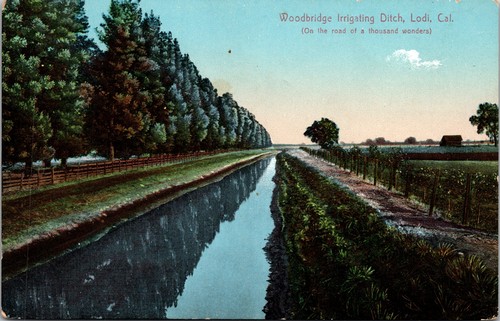

If you came to the region now known as Lodi in, say, the 1600s or 1700s, you would see a metropolis of towering trees⏤particularly valley oaks, the one species of Quercus demanding the richest and deepest possible soils⏤fed by wild and uncontained rivers teeming with wildlife.

In Jessie's Grove estate, a large stand of valley oaks—a species of oak demanding the richest and deepest of soils with ample water resources—native to Lodi's Mokelumne River appellation.

Yes, the successions of Spanish, Mexicans and finally Americans have changed the landscape, yet the fundamental terroir of Lodi remains. It is more like a green and lush oasis that your mind imagines after crawling for miles across parched deserts. Only, Lodi is very real. As an appellation, it is the home of more European wine grapes than any other region in America (more acreage than Napa Valley and Sonoma County combined... heck, more than the entire states of Washington and Oregon combined, plus more!). Grapes love Lodi.

Logically, this should tell you that Lodi is, plain and simple, an ideal place for wine grapes. Yet one of the biggest myths endlessly repeated wherever wine knowledge is bandied about is this: That warmer climate regions always produce heavier, riper wines with lower acidity, whereas cooler climate regions always produce lighter, finer wines with higher acidity.

Photograph on early 1900s postcard showing off the generous waterways and vineyards of the Lodi appellation.

There are two reasons why this assumption is very wrong, so very wrong:

1. There is an increasing number of wines grown in Lodi's warm climate that are the opposite of what is commonly assumed⏤lighter in weight and alcohol, emphatic in natural grape acidity, and with fruit profiles that are not only subtle in "ripeness" but also tinged with non-fruit (especially mineral or earthy) qualities.

2. California wine regions known for cooler climates than that of Lodi's, from Santa Barbara all the way up to Mendocino, can and often do produce fuller bodied wines with lower acidity, higher alcohol plus riper tannin and fruit flavors, not much different from what you expect out of Lodi.

Grapes ideally suited to Mediterranean climate terroirs defining Provence and Lodi: (clockwise from top-left) Grenache, Vermentino, Carignan and Piquepoul.

Number one is the factor of grape varieties. Certain European wine grapes, falling in the family known as Vitis vinifera, have been developed over hundreds (if not thousands) of years precisely to produce light zesty wines, no matter how hot the climate. Biologically, it's called adaptation of suitable species.

France's Provence, for instance, is a vast winegrowing region which the French gleefully describe as "hot" because, as a matter of fact, it is much warmer than other regions such as Burgundy or Bordeaux. This is precisely the reason Provence specializes in grapes such as Grenache, Cinsaut, Carignan, Rolle (a.k.a., Vermentino) and Piquepoul (a.k.a., Picpoul blanc)⏤because these grapes produce light, zesty, refreshing wines because of Provence's warm to hot climates.

Ancient vine own-rooted Lodi growth dating all the way back to 1886: Bechthold Vineyard Cinsaut.

You will not, for the same reason, find Grenache, Cinsaut, Carignan, Rolle or Piquepoul in Burgundy or Bordeaux (although climate change may alter that equation somewhere down the road); for the same reason you won't find Pinot noir and not so much Cabernet Sauvignon or Chardonnay in Provence. After accumulating centuries of viticultural expertise, the French have figured out what grapes are best for each region: That is, the grapes that give them the highest percentage chance of producing high quality, well balanced wines, with a minimum of artifice or manipulation.

There is another reason, though, which explains why perfectly light, refreshing and balanced wines can be produced in the hottest regions. It is the simple fact that wines don't make themselves. While environmental factors such as climate and grape selection determine how wines turn out, just as big are the decisions made by the growers and vintners themselves.

1912 photo of Spenker Ranch in Lodi's Mokelumne River appellation, showing head trained grapevines that are already fully matured. Wanda Woock, Jessie's Grove.

Therefore, a Pinot Noir producer in, say, Santa Barbara's Sta. Rita Hills or Sonoma's Russian River Valley may very well choose to pick grapes with high enough sugars to produce bigger styles of the varietal (over 14.0% alcohol) possessing ripe, opulent qualities; and, in fact, because these styles of Pinot Noir are very popular (and also garner high "scores"), many of California vintners are producing exactly this style of wine.

The same for other popular varietals, such as Chardonnay, Cabernet Sauvignon and Zinfandel: Some of the biggest, ripest, heaviest styles of these varietals come from regions that have demonstrably cooler climate growing seasons than Lodi. These are the choices made by winemakers and brands.

Recently, by the same token, we have enjoyed a bottle of white wine crafted by a vaunted Lodi winemaker named Markus Niggli. The wine, Mr. Niggli's 2014 Markus Wine Co. Lodi Nativo (a blend of 75% Kerner with Riesling and Bacchus grapes), was over 10 years old but still tasted fresh as a daisy, light as breezy spring air, and crisp as a crunchy, just-plucked apple. Defying, on every level, all of the myths about Lodi as being too warm a region to produce anything but big, fat, heavy or overly fruited wines.

Picking Kerner, a grape of German origin, in Lodi's Mokelumne Glen Vineyards.

Niggli has been producing these exact styles of white wine in every vintage for over 15 years. How does he to do this? Through black magic, or sneaky winemaker machinations? The answer, simple enough, is twofold:

1. Lodi's terroir permits it.

2. Because he can.

That is, re point #2, Mr. Niggli is smart enough to pick these grapes when they are still low enough in sugar and high enough in acidity to end up with a light, zesty wine that is as minerally as it is floral or fruity.

In respect to terroir, while Lodi's climate can be described as "hot," the region's growing seasons are marked by the exact same diurnal fluctuations (i.e., cool nights, warm days) typifying almost the entire California coast. Because of that, you can ripen grapes in Lodi that retain both natural acidity and a freshness of fruit profiles. This is also the key to producing wines that can age gracefully in the bottle for over 10 or even 20 years, which Lodi also does.

Albariño, a grape of Spanish origin, which produces white wines with zesty natural acidity, lightness and minerality in even the hottest climates of California.

Niggli's Nativo, however, is not exactly an outlier, or rare freak of nature. There are approximately a dozen and a half brands of Lodi-grown Albariño, a Spanish grape native to the north-east tip of Spain along the Atlantic coast, that taste just as light, zesty in acidity, fresh, floral and minerally as just about all the Albariños imported from Rías Baixas, considered one of Spain's cooler climate regions.

Lodi Albariños are comparable to any grown in the world for the exact same reasons why the Markus Wine Co. Nativo ages effortlessly in the bottle for over 10 years: Because Lodi winemakers are smart enough to make them that way, and because Lodi's terroir makes it very much possible.

Other handcraft producers are achieving similar results, employing guile as winemakers and savvy as grape sourcers. Craig Haarmeyer's Haarmeyer Wine Cellars Lodi Chenin Blanc, for instance, is always every bit as sharp in acidity, and as stony as well as flowery-fresh as any Chenin Blanc in California⏤and for that matter, as much as any Chenin blanc-based white coming from the grape's native habitat in the Loire Valley of France.

Harvesting of Alta Mesa-Lodi Chenin blanc—a grape variety that originated in France's cool climate Loire Valley, yet retains a steely, zesty, fresh fruit/acidity profile in warm climate's such as Lodi's when picked earlier in the season.

Speaking of effortlessmess: Acquiesce Winery owner/grower Sue Tipton has been doing the same with her portfolio of over a dozen varietal whites and blends over the past ten or so years. In blind tasting professional competitions, Acquiesce whites predictably clean up, garnering every "Best of Class" or "Best of Show" award there is to win. Not surprisingly, Tipton was named "Woman Winemaker of the Year" at the 2022 International Women's Wine Competition.

None of this happened because Acquiesce produces big, fat, heavy, overripe wines. Today's professional wine judges don't give out awards for clunky wines. It's not the fashion. But Acquiesce is fashionable because it produces lithe and delicate, finely balanced and restrained wines reminiscent of (you got it!) wines grown in cool climate regions.

Acquiesce Winery owner/grower Sue Tipton with clusters of Grenache blanc and Grenache noir, among the multiple Southern French grown on her estate that are ideally suited to Lodi's terroir.

Point being, it is time to put many of these myths⏤these squarely wrong assumptions⏤to bed.

Yes, Lodi is Zinfandel country, but the exact same climate and soils that make it so easy to grow Zinfandel also furnishes a natural proclivity to grow a wide range of grapes for whites, reds and rosés that are just as light and crisp, and just as airy and refreshing, as wines grown in practically any other region in the world.

The myth that Lodi doesn't produce light, crisp and airy wines is exactly that—a myth. Excuse me, while crack open another bottle of Zinfandel.

Lodi's Marian's Zinfandel—Zinfandel planted in 1901—marked by its sign for Historic Vineyard Society certification.