Letters from Lodi

An insightful and objective look at viticulture and winemaking from the Lodi

Appellation and the growers and vintners behind these crafts. Told from the

perspective of multi-award winning wine journalist, Randy Caparoso.

Monte Rio's Patrick Cappiello gets things off his chest while producing an astounding range of Lodi grown wines

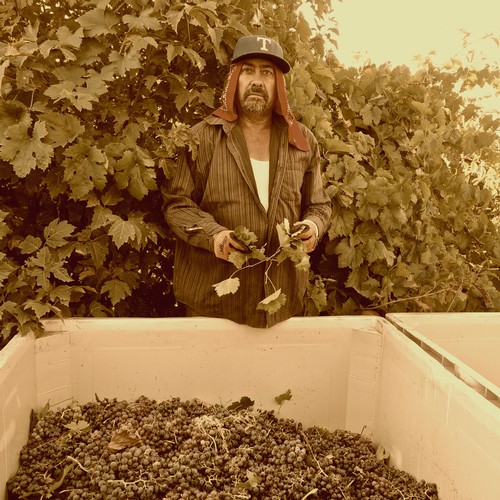

Monte Rio Cellars owner/winemaker Patrick Cappiello. Leigh-Ann Beverley.

This past mid-December I was walking along a beach in Hawaii, toes squishing along in wet silky sand, when the phone in my board shorts rang. It was Patrick Cappiello, owner/winemaker of Monte Rio Cellars, a Sonoma County-based brand that has been making quite a name for itself for naturalistic style wine—most of it sourced from either super-old vines or regeneratively or biodynamic farmed grapes here in Lodi (see notes on latest releases at end of article).

Monte Rio, Cappiello called to say, was reaching an impasse. The brand was satisfactorily established in key markets, and the wines were better and more multifaceted than ever. But for whatever reason—primarily, no doubt, because of an overall market malaise—sales had recently stagnated. Monte Rio seemed to be fulfilling an old industry adage, that is is a lot easier to make great wine than it is to sell it.

Cappiello's one-man business (he employs just one person other than himself, assistant winemaker Jesus Aleman) needed a jump-start. Stat.

Monte Rio Cellars assistant winemaker Jesus Aleman (left) and owner/winemaker Patrick Cappiello. Leigh-Ann Beverley.

Not that Cappiello is one to panic. Before going into the business of producing and selling wine, he worked for over 30 years in the New York restaurant industry, primarily as a sommelier, manager or part-owner. People like Cappiello don't panic when times get tough or when they find themselves (borrowing restaurant lingo) "in the weeds." They pick up a shovel and start digging.

At the start of the new year (2024), Cappiello found his most effective digging tool on Instagram, harnessing his @patrickwine page to post reel after reel reaching directly to consumers, one-on-one (or rather, two-on-one, as Aleman is also a constant presence).

There is nothing unusual about utilizing Instagram as a marketing tool. What's more unusual is what Cappiello has had to say: Less about the cute "look-at-me" or "aren't-we-cool?" reels set to nostalgic music which typify most winery handles and also dominated @patrickwine up until recently. Instead, Cappiello has opted to conduct almost sobering, straightforward, hardcore, honest and sometimes brutally self-examining conversations about his winemaking, and what he thinks about the wine industry in general.

Recent post on Instagram's @patrickwine page showing just a few of the current Monte Rio Cellars releases.

Cappiello's breast-baring posts have been relentless to the point of accumulating over 37,000 followers (a huge amount by tiny winery standards). More significant, though, has been the responses, some of them broadcast far beyond the micro-universe of @patrickwine.

Exhibit #1 popped up in a March 8, 2024 Substack article by Ari Bendersky entitled The Case to Drink More American Wine. Bendersky starts off by quoting directly from a Cappiello reel on Instagram:

“American wineries are struggling right now. We have a huge amount of inventory and a huge decrease in sales. And you can help us. We are asking you for one thing: Drink our wines. Buy our wines.” With that plea on Instagram, Monte Rio winemaker Patrick Cappiello urged American wine merchants, restaurant and bar wine buyers, sommeliers, and consumers to only buy and consume American wine for the next two months.

While conglomerates like Constellation Brands, Gallo, and Trinchero Family Estates, which all own and operate numerous wine brands with revenues in the millions, would survive, it’s the smaller labels—many of which often fly under the radar among everyday wine drinkers—that are struggling.

Monte Rio Cellars owner/winemaker Patrick Cappiello. Leigh-Ann Beverley.

“If we don’t shift the focus now to concentrate on drinking domestic wine and supporting domestic producers,” Cappiello told me on a call last week, “then the producers that have worked so hard to build change on what we’re doing here are the ones who are going to fail.”

Cappiello said his sales in the first two quarters of 2023 were stellar, but then in August, he saw an 80% drop from the previous year and, overall, saw his sales decline 20% for the year. “I didn’t overproduce,” he said. “I produce based on my sales trajectory and we’re dependent on what our distributors are telling us what they want and need.”

Winemakers order grapes from dedicated wine-growing farmers (if they don’t own their own vineyards), but sometimes they can’t make good on those orders. The decrease in consumer demand is forcing growers to tear out thousands of acres of vineyards. The Lodi, Calif., area is being especially impacted. As the largest winegrowing area in the nation, by tonnage, Lodi’s growers have seen demand plummet and, in turn, are scrapping a lot of planted vines. Industry leaders in California have called for the removal of nearly 10% of planted acres—about 50,000 in total.

“We’re trying to hold our agreements with our farmers, who have left a lot of fruit on the vine,” Cappiello added. “In Lodi, they were f--ed. The big brands in California left a lot on the vine. Many young producers, including myself, had to call farmers and tell them they could try to sell fruit to other places because we may not have been able to pay.”

Monte Rio Cellars' Patrick Cappiello sharing a moment in Lodi' Somers Vineyard with friends. Leigh-Ann Beverley.

Exhibit #2, posted in Forbes (May 6, 2024), was an article by Jill Barthes called Does Drinking Local Matter? This California Winemaker Says It Does. Barthes repeats Cappiello's dire warnings, while adding:

Before making his first vintage in 2018, Cappiello logged decades of experience as a sommelier in the restaurant industry, and he’s no stranger to wine from places other than the United States. Over the phone, Cappiello emphasized that he’s not calling for a boycott of imported wine. On the contrary, his request encourages everyone worldwide to support local businesses

... Cappiello’s point is that, given the wide range of options at our stateside doorstep, perhaps everyone could spend the next few months exploring closer to home. And, in the effort, ramp up sales and energy around the more than 11,000 wineries we have in the United States, over half of which are micro-businesses, producing less than 1,000 cases, according to fresh data from Sovos ShipCompliant.

Of course, you can say that Cappiello's "Drink American" exhortations are not entirely altruistic. It just so happens that they also reflect the exact same sentiment shared by most of the American wine industry. Re Lodi Winegrape Commission Executive Director Stuart Spencer's own recent article Imported Foreign Bulk Wine: The Dirty Secret No One in California Wine Is Talking About which has been spreading like wildfire throughout the wine world over the past two months (also see Los Angeles Times' Global wine glut compounds headaches for struggling California vineyards).

Jesus Aleman tasting through Monte Rio Cellars barrels. Leigh-Ann Beverley.

While Cappiello has been speaking out primarily for small wineries, Spencer has been speaking for the entire California wine grape growing industry. “What’s aggravating," says Spencer, "is that we have grapes that didn’t get picked or sold while the biggest wineries in the state are bringing in cheap bulk wine from overseas.”

Exhibit #3 is an April 29, 2024 Punch story by John McCarroll entitled Was California's Wine Revolution Just a Mirage?, prompted by Cappiello's challenge to "drink more domestic wine." McCarroll starts off by citing The Golden State's penchant for catastrophes, natural and figurative, which are

... doubly true in wine. Disasters and freak incidents that would shock any other wine-producing region—floods, fires, earthquakes, sometimes all in a single calendar year—seem to occur with depressing frequency in California. It’s a place where we are so used to bad things happening that we fail to notice them getting worse. Case in point: Today, California is home to one of the greatest concentrations of talented young winemakers in the world, and yet many of them will tell you that they are one step away from hanging it all up for good.

... Small California winemakers, without land, have very few backup revenue streams. “No bank is going to give [small winemakers] a loan,” says [Megan] Bell [owner/winemaker] of Margins Wine. “They know we’re a bad investment.”

Straw covered fiasco of Monte Rio's biodynamic-grown Lodi Sangiovese. Leigh-Ann Beverley.

... All of this adds up to winemakers who begin their vintage almost comically in debt. In such an environment, there’s tremendous pressure to sell out as quickly as possible, even if it requires lowering prices beyond a sustainable point. As recently as 2022, winemakers could depend on mailing lists, wine clubs and direct-to-consumer sales to keep them afloat, but that revenue stream has dried up for many, cutting their margins precipitously and forcing them to compete for spots on lists and shelves with overseas producers who have less overhead.

Exhibit #4 is a little more sensationalist (as such, partly dubious): An April 7, 2024 Robb Report filed by Mike DeSimone and Jeff Jenssen casting doubt on the very efficacy of the Monte Rio Cellars style of wine, which Cappiello first brought into question in one of his own posts. The title of the piece says it all, One of Natural Wine's Biggest Advocates Isn't Into Natural Wine Anymore—Here's Why, starting off with a quote direct from a Cappiello reel...

"So I’m going to get to my point pretty quickly here, but last week I talked to you about being transparent and telling you everything that happens in the winery, and I spent this weekend really struggling with next steps and wanting to be honest.” [Cappiello] went on to explain that after tasting some of the older vintages of his Monte Rio Cellars wine, the sommelier-turned-winemaker found that they were “not only not good, but undrinkable,” leading him to realize he needed to filter his wines and add sulfur to make them stable.

Patrick Cappiello. Leigh-Ann Beverley.

... In his Instagram video, Cappiello says he is finally speaking out despite the “fear of dogmatic gatekeepers in the sommelier or wine merchant community, which I used to be a part of, that dictate that doing something like this makes your wine unnatural.” He explains, “I am trying to call out sommeliers who have never made a bottle of wine or risked their life and finances to start a winery. I’m not going to be beholden to them anymore.”

"My terminology was always that I make wine naturally, not that I’m a natural winemaker. Because, first of all, I think that that word has not been defined, and to say something is natural wine is dangerous because there is no set definition of the terminology and it’s been a long-discussed thing. But also, it was a club that I did not necessarily want to be a part of. Being a natty wine producer, to really bro it down, it just didn’t feel right to me. Do I consider myself a natural winemaker? In the end, I don’t know. I don’t know if I do anymore, but I thought I was. I guess other people will have to make that decision for me."

Majestic heirloom Flame Tokay in Lodi's Chandler Vineyard, dating back to the 1890s.

A few current (and incredibly juicy) Monte Rio Cellars releases

While Cappiello may have, for all intents and purposes, turned in his membership card to the proverbial (and really, nonexistent) "natural wine club," the fact of the matter is that he and Aleman apply virtually all the techniques that typify contemporary low intervention style winemaking: Foot treading, native yeast and whole cluster fermentations, picking early to attain lower alcohol and higher acidity, as little oak influence as possible, and so forth.

Cappiello's reasoning is the opposite of the nebulousness non-natural wine proponents expect out of this kind of winemaker. In a conversation last year, he plainly stated his goal: "To give a pure platform for the terroir and varietal characteristics to show through. These fermentations tend to... amplify the more savory and mineral characteristics as opposed to amplifying the fruit characteristics, which we have an abundance of naturally in our wines in California."

Here in Lodi, we have been supportive of Mr. Cappiello's endeavors ever since his first vintage (2018) because, well, he produces a style of wine that "amplifies" Lodi, where he sources most of his fruit. As far as we're concerned, the more a wine is made to taste like it comes from Lodi, the more it helps us get our own message out to the world—that Lodi farmers grow damned good wine grapes.

Discarded Zinfandel cluster on sandy loam soil along the banks of the Mokelumne River.

For example, a pure, unadulterated style of Zinfandel—the appellation's signature grape and varietal wine—tends to be more floral, a little earthier, and more gentle in phenolic content than Zinfandels grown elsewhere in California. Therefore, Cappiello adjusts his winemaking to highlight the floral, earthy and rounded textures of his Zinfandel. Sounds reasonable to us.

Many wine lovers consider this style of winemaking to be "natural," even if the defining practices pertain more to what happens in a winery than what is being done in vineyards. Others would just as soon think about it as just another winemaker being true to his sense what makes "good wine" good. Who cares what you call it?

For a little-winery-that-could, though, Monte Rio Cellars' portfolio is large, diverse and, in a lot of ways, novel; taking full advantage of the wide range of grapes and vineyards in Lodi, available to small, handcraft vintners. Below are our notes on just seven of the over dozen-and-a-half bottlings currently offered by the winery.

Monte Rio Cellars' Patrick Cappiello. Leigh-Ann Beverley.

The multiplicity of SKUs, of course, is only inevitable for a brand that values the individuality of vineyards. Cappiello and Aleman would much prefer to bottle vineyards separately rather than dumping them all into one big, homogenized pot. They are wine geeks, making wine for geeky consumers.

The overall house style is light and perky, presumably in order to be more food-friendly (befitting Cappiello's restaurant background). There is no effort to be "big," "hedonistic" "intense," prim, proper, predictable, or whatever fits into conventional expectations of commercial or even highly "rated" wine. If you like it, cool. This little winery could use the support. But if not—well, I guess they may very well go down trying. Like Cappiello himself, the wines wear their hearts on their sleeves.

2023 Monte Rio Cellars, "Chandler" Lodi Flame Tokay ($29)—This transparently rusty orange-tinted wine falls within the brand's "Ancient Vines" series, clearly marked on the front label. It's ancient, alright; coming from giant, own-rooted Flame Tokay vines originally planted in the 1890s by a historic Lodi figure named Zella Hansen, and currently owned by a successful realtor named Karen Chandler (Chandler also sells olive oil from trees planted between the ancient vines). You can appreciate this wine like a rosé, but it's not really a rosé. Rather than perfumey or redolent with berry-like fruit, the nose is demure, suggesting orange pulp, peach fuzz, a trace of rose petal. The wine is dry as a bone, soft and light-medium in body (12.5% ABV), yet fluid and mildly fleshy, finishing with the plump assuetude long known to locals who still remember this heirloom variety as Lodi's signature table grape. If you are looking for "unique," this is as unique as it gets.

Somers Vineyard Mission grape harvest, east side of Lodi's Mokelumne River AVA.

2023 Monte Rio Cellars, Lodi French Colombard ($24)—Although Colombard, long known as a workhorse grape for jug wine "Chablis," is still widely planted in the southern districts of California's Central Valley, it has all but disappeared in Lodi. Hence, now considered an esoteric, if not curious, varietal. As is his wont, Cappiello stumbled upon a forgotten stand in a vineyard along Tretheway Rd. south of Victor Rd. on the east side of Lodi's Mokelumne River AVA. As a jug wine, the varietal was always prized for its "neutral" profile—old school generic Chablis was always meant to taste light and inoffensive, going down as easily as water—but this bottling, given handcraft attention, comes across as light (just 11.5% ABV) yet almost brazenly flavorful, like a 10-year girl with a black belt's karate kick. The nose suggests grapefruit skin, a snip of leafiness and melon/pear-like fruit. On the palate, the low-key profile comes across with a sense of earthy minerality; dry, mildly tart, sleek, supple. Makes your palate water for white Hawaiian fish like mahi-mahi, dolled up with little more than lemon.

2023 Monte Rio Cellars, "Somers" Lodi Mission ($24)—I suppose we didn't have to cover this wine—made from a pre-statehood grape that the California wine industry has been trying to run away from for over 170 years—because we've highlighted previous vintages before. But doggone it, remarks on pure varietal Mission bear repeating because many of today's consumers are looking for exactly this kind of red wine: Pale, transparent, unabashedly wimpy in ruby red color, and light (12% ABV) and as ultra-soft as, well, a baby's bottom. The opposite of "big." But oh, the nose—soaring in tingly kitchen spices, flowery red berries. It is flush and compelling, especially in its near-naked (rounded out in neutral barrels to garner zero "oakiness") palate feel, refreshingly plain yet pliant, freed from enslavements of oak.

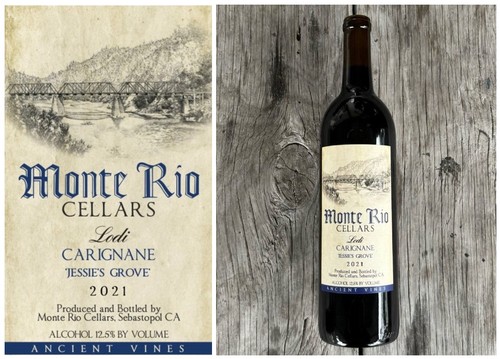

Monte Rio Cellars' "Ancient Vines" series wines—generally sourced from vineyards over 100 years old—are noted at the bottom of their front label.

2022 Monte Rio Cellars, "Jessie's Grove" Lodi Carignane ($29)—Another one of the winery's "Ancient Vines" wines, sourced from a historic, own-rooted, west side Mokelumne River-Lodi block planted in 1900. Carignan is a quintessential Mediterranean grape, so well suited to Lodi's Mediterranean climate that grapevine longevity is practically a given—all the more reason to support the sincere efforts of this winery to help revive interest in this underappreciated grape. Like virtually all of the Monte Rio reds, there is an overriding sense of purity to the fresh, bright, black and red berry aroma, manifested in rounded yet well-delineated, acid-driven flavors. The loamy earthiness typifying many west side Lodi reds emerges on the palate, mingling with the unadulterated fruit in a zesty, restrained medium weight (12.5%) body, pushed forward by just moderate tannin.

2022 Monte Rio Cellars, Lodi Carbonic Zinfandel ($25)—Old-timers can recall when this style of wine (technically defined as carbonic maceration) was typically marketed as "Nouveau," à la the quaffing style reds descending upon us from Beaujolais in France every fall. True to the tradition, the aroma is bright and lively with red berry perfumes; only, tinged by a very "Zinfandel" peppery spice, plus an earthiness reflecting the appellation. While super-soft and easy drink (12.9% ABV), it is zesty with acidity in the mouth, strongly suggesting a good cheeseburger (chile peppers or Tabasco-laced ketchup would enhance the varietal spice), if not salmon, tuna, and/or caps of portobello hopping off a fiery grill.

2022 Monte Rio Cellars, "Faith" Lodi Zinfandel ($29)—Have you noticed the suggested retail prices of these wines? Let's spell it out: A ludicrously low $29 for this particular edition of the winery's "Ancient Vines" series, sourced from an own-rooted 106-year-old vineyard, sitting alongside the landmark Kirschenmann Vineyard (planted in 1915 and bottled by Turley and Sandlands) and Katushas' Vineyard (another 1915 block, owned and bottled by Bedrock Wine Co.). Come on, old vine wine lovers, what more do you want? Kudos to Cappiello and Aleman for checking their winemaker egos at the door and going to great lengths to preserve the east side terroir of this site: Soaring in ultra-bright Bing cherry/raspberry fragrance with a touch of a floral (almost jasmine-like) tea, as pure and unmitigated in the nose as it is on its silken textured palate, perky with acidity, taking on peppery spice in a long, buoyantly weighted (just 13.5% ABV) finish.

2022 Monte Rio Cellars, "Marian's" Lodi Zinfandel ($29)—Even among Lodi's own longtime homegrown vintners and growers, there may not be a single vineyard as revered as Marian's, originally planted by a branch of the Mettler family in 1901. It is iconic because of the red wines associated with the growth, known for a textural opulence considered to be ideally "Lodi." Although it is a west side growth, the earthiness typifying Zinfandels on this side of the track is subtle to the point of being just a backdrop to a profile of plummy dark fruit, spiced black tea and blueberry liqueur. What defines the wine most of all is its mouth-filling (despite a restrained 13.5% ABV) quality; flavors that come across as wall-to-wall yet very bright and upbeat, lifted by a seamlessly integrated, entirely natural balance of acidity and tannin. The respectful, hands-off approach of this brand helps to celebrate the vineyard, and Lodi, itself. Let's hope it's appreciated well enough!

Marian's Vineyard, own-rooted Mokelumne River-Lodi Zinfandel planted in 1900.