Letters from Lodi

An insightful and objective look at viticulture and winemaking from the Lodi

Appellation and the growers and vintners behind these crafts. Told from the

perspective of multi-award winning wine journalist, Randy Caparoso.

Wine tasting is easy

Tasting wines with foods, which all visitors to Lodi's Acquiesce Winery do.

First things first.

You may have heard, or maybe just assumed, that appreciating wine is complicated. That it takes an "expert" to truly understand and enjoy wines. I have just one word to say about that: Untrue. Anyone who tells you wine is complicated has no idea what he or she is talking about.

Let me tell you why. Where, in fact, do you find the most people happily consuming wine like there's no tomorrow? People who drink wine as an everyday beverage, like we do coffee or Diet Coke? If you guessed Europe⏤countries such as France, Italy, Spain and others nearby⏤you have, of course, guessed correctly. Most people know that this is where wine was invented. Do you think the gazillion wine lovers in those countries had to take wine courses, do deep reading or applied themselves to the "mastery" of wine knowledge in order to appreciate wines? Of course not!

Europeans, of course, have the advantage of taking to wine consumption easily because it's part of their culture, the same way that hot dogs, cheeseburgers, pickup trucks, blue jeans and apple pie are in ours. No one had to teach us how to appreciate blue jeans or cheeseburgers. Oh, maybe someone, like your mom or grandma, had to teach you how to bake an apple pie, but we all know a good apple pie when we see, and taste, it (in Lodi... Phillips Farms Café at Michael David Winery!). None of this is complicated.

Classic photo of French woman in 1945—with baguette and bottles of wine—on the streets of Paris. Branson Decou.

Most Europeans "know" wine easily enough and they would laugh if you asked them if they had to "study" it first. To them, wine is no mystery. There is no "secret language" to unlock, no detriment to enjoyment.

Appreciation of wine is no different than most things. Sure, it helps to pick up a book or do a little online reading to find out about this wine or that, but when you think about it, that's exactly what we do with just about everything. When we land in a new city, for instance, we do a quick spin online to find out what the best restaurants are at the moment; where to shop for shoes or vintage clothes, where find the best beaches or nightclubs, the right amusement parks or museums for kids, and on and on. This is everyday, garden variety "research," not studying towards a PhD.

Appreciating wines, no matter how complicated and varied they can be, is as easy as apple pie because most of us have brains. We can all easily put two and two together, even with even minimal information, of which there is never any shortage.

Visiting sommelier tasting wine among old vines in Lodi.

Even walking into a big, cavernous wine store is not nearly as scary as you might think. It is not much different from walking into, say, an Apple store, which many of us end up doing every year or two anyway. When we go to an Apple store, do we walk in with a built-in understanding or mastery of all the latest technology going into iPhones or iMacs? Of course not. But we usually walk out with a deeper understanding of them because there are people in these stores who are more than willing to explain the uses of the most complicated devices, in ways anyone can understand.

Discovering new, fun, even super-complex wines, either in a fancy store or a stuffy restaurant, is absolutely no different. New wines always start off challenging, maybe even a little intimidating, but once you're into them they're as easy to understand and appreciate as anything. In fact, the more challenging the better. Everyone enjoys an adventurous experience.

Ergo: There is absolutely no reason to fear wine⏤even the finest, rarest or most esoteric wines. There is even no reason to fear luxury priced wines for the simple reason that when a wine tastes really good, whether very cheap or very expensive, most of us can recognize that fact, the same way we know a good song, a great car, a well fitting pair of jeans or a fun, engrossing book when we come across them. With most products, we don't need to be able to recite the science or artistry behind every component in order to appreciate it. All we need to know is how much we enjoy them.

In Lodi's Clements Hills appellation: Friends don't let friends drink lousy wine.

Rule #1⏤There are no rules

Let's begin with the first and most basic rule of wine tasting: There is no such thing as the "right" way to appreciate wine. The vast majority of wine lovers⏤especially those in countries where wine has been consumed for centuries⏤rely on their own instincts when deciding upon which wines they like the best, and which wines they don't like at all.

You may prefer a wine that is very light, soft and fruity, or you may prefer a super-heavy dry wine that is hard or edgy to the taste. It's all good. You really don't even need to know the words to describe what you like or don't like. You just know. Just like you know whether you prefer hard rock or easy going pop music, country music or classical music, jazz, reggae, punk, headbanger, you name it, it doesn't matter: No one can tell you what you like best, except you.

The only thing we can tell you, based upon experience, is this: The longer you're into wine, the more your taste tends to change. This has nothing to do with having "good taste" in wine. It has everything to do with being human. As time goes by, most of us usually change⏤maybe just a little, but quite often quite a lot.

That said, let's talk about a few things that will help you understand your own preferences. Things that will help you get the most out of every glass you sip, every bottle you buy.

First things first: Get a good wine glass.

#2—The basics of wine tasting

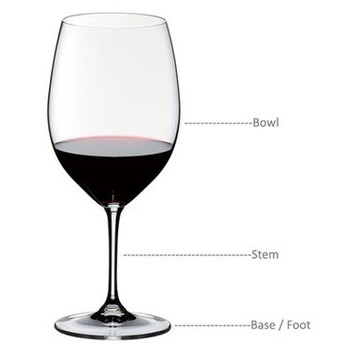

First, get a good wine glass. Wine tastes better in wine glasses⏤especially those with stems, that have a clear tulip shape and a fairly thin (rather than thick and beady) rim where your lips touch the glass. We'll explain why later.

Second, tasting wine is just like tasting food except for the fact that it involves examining liquid (with alcohol) in a glass, and getting accustomed to the process which involves...

• Seeing

• Swirling

• Smelling

• Sipping

Third, it helps to be able to use words to describe wine to yourself; and, if you happen to be in good company, communicating tastes to other people. Wine, if anything, is an extremely social beverage. It's like "vinyl night" at home: Talking about a classic Chuck Berry or favorite Ella Fitzgerald record makes sharing all the better. But as we said, the "language of wine" is no mystery; neither is it complicated. In fact, you need to know just a few common sense words to talk about wine, which helps your remember the qualities of each wine you taste.

Tasting Zinfandels at the Lodi Wine Visitor Center.

#3—All the words you need

Color or appearance⏤Is a wine still or sparkling… pink, a pale or golden white, or red as in a deep purplish ruby or a lighter, brick toned burgundy?

Aroma⏤A wine's smell, which which becomes a wine's "flavor” once it hits the palate... what does a wine remind you of—a certain fruit, a spice, a flower, or even mineral or sense of earthiness?

Dry or sweet⏤Does a wine have some degree of sweetness, or none at all (a wine with no perceptible sweetness is considered "dry")?

Body⏤A wine's weight or feel on the palate (is it light, full, or just “medium” in body)?

Acidity⏤Level of tartness derived from acidity in the wine (since wine is made from grapes, it usually retains a little acidity natural to the fruit), especially in whites and sparklers, and to a lesser degree in reds... is a wine zesty or tart, or the opposite, soft and round?

Tannin⏤The component pertinent to red wines since tannin comes from skins and seeds (red wines are fermented with skins and seeds, whereas white wines are fermented after pulp is separated from skins)—is a red wine big or hard in tannin, or is it light, soft, or just moderate in its tannin?

Origins of the sensory quality of tannin tasted in wine. winefolly.com.

That's it, all the words you need to help you distinguish one wine from the other. Once you get comfortable notating these qualities to yourself, you are essentially using the exact same words utilized by Masters of Wines or Master Sommeliers when describing wines. It is not complicated.

The only difference between novice wine consumer and a "Master" is that the latter tastes a lot more wine⏤enough to have passed tests to demonstrate he or she can make delineations among the thousands of wines grown and produced around the world. Otherwise, you follow the exact same steps when tasting a wine, and use the exact same words when describing it.

#4—Appearances

As Yogi Berra might have put it, you can see a lot by looking. It is as important to look at a wine as it is to first look at a dish before you eat it because our sense of smell and taste are directly connected to the visual impressions collected by the brain. For instance, if you see a comfy looking chair, you know that most likely your bottom will thank you for sitting on it. If you see a hamburger, you expect something meaty and drippy, and maybe a mildly crunchy if there’s a fresh leaf of lettuce, sliced tomato or pickle in it.

Many of the sensory qualities that can be perceived by looking at the color of wines. winefolly.com

By the same token, if you see a white wine, you expect something cool and refreshing. Red wines usually get your senses ready to taste something dryer and meatier. Sparkling wines typically signal a wine that will most likely taste a little tart and lively with foamy effervescence.

#5—Smells

Then you begin the process of tasting, which you start by swirling. Swirling wine in a glass is not an affectation. The reason you swirl is to allow a wine to fall down the sides of a glass, which creates the vapors that you smell and perceive as aromas. It is the smell of wine that distinguishes one wine from another, the same way that it is the smell of food that distinguishes one food from another (like the difference between the smell of an apple and an onion).

Without the activation of your sense of smell, all foods, and all wines, taste pretty much the same (ask anyone who has lost their sense of smell for a period of time).

Lorenza Wine's Michele Ouellette swirling a tank sample of Lodi Picpooul Blanc in her glass, just before tasting.

Swirling wines is also why good wine glasses are usually clear and tulip shaped, with rims that are curved inward plus a stem to help you hold the glass without getting your fingerprints all over the bowl. A curve-shaped glass also helps you swirl the wine without spilling it on your shirt or blouse. The act of swirling works best if you pour a glass only about a third full at a time, thus enhancing the smell of vapors collected beneath the rim.

When examining a wine's scent, start by holding your glass by the stem and gently twirling it in a circular motion. If this feels awkward, move your glass around in a little circle as it sits on a table.

After that, you take a little sniff. As you bring your nose to the rim of the glass, open your mind up to what it reminds you of. White wines made from the Chardonnay grape, for instance, usually trigger memories of apples, maybe pear or lemon, often even a tropical fruit. This, simply, is how the brain works: It relates sensory impressions to what you've experienced in the past, which you carry around in your head, or memory bank. Pay attention to your "taste" memories whenever you smell a wine.

Red wines made from Cabernet Sauvignon grapes, as another example, are often reminiscent of dark or red fruits such blackcurrant and berries, sometimes with a little bit of mint or eucalyptus. If the smell of mint or eucalyptus is not at the front of your brain, don't sweat it. If your impressions are on the vague side⏤a Cabernet that just tastes like "some kind of dark fruit"⏤that's fine, too. The more important thing is to smell a wine and decide whether you like it or not.

Visiting wine influencer tasting a Carignan cluser in a Lodi vineyard to understand the taste of Carignan based red wine.

Lodi, you may have heard, is the "Zinfandel Capital of the World." We grow more of that grape than any other region. The grape would not exist in vast acreage, however, if people didn't appreciate the specific taste of Zinfandel, a lot of which is defined in the nose. Red wines made from Zinfandel often have that blackberry, raspberry or cherry-like aroma with a touch “jammy” sweetness in their scent (even if the wine is completely dry on the palate, which it normally is); often with a backdrop of spice (usually suggesting cracked black pepper, although sometimes like cinnamon, clove or other kitchen spices).

In recent years, Northern Europeans have picked up a taste for Zinfandel. Lodi wineries are exporting boatloads of that wine to countries such as Sweden, Norway and Denmark⏤most likely because it's identified as a very "American" wine (like blue jeans and Taylor Swift for clothes and music), and also because they like the spiced berry taste of Zinfandel. It's not a "rocket science" thing. It just is what it is, without anyone having to think deeply about it.

While European wines are usually sold by the names of their region of origin, American wines are sold by brand and varietal identification (i.e., the names of the grapes that wines are made from, such as Chardonnay, Sauvignon blanc, Cabernet Sauvignon, Zinfandel, etc.). Paying attention to the smells of fruit suggested in a wine's "nose" helps you learn the different varietal characteristics; and after you learn that, you can better appreciate the way each brand, and each wine region, interprets "varietal character."

Winter tasting in Lodi winery.

#6—Tastes (in the mouth)

Finally, after focusing on smells, you actually sip a wine. For wine, this entails a discovery of how the natural elements of alcohol, acidity, and (for red wine) tannin come together with the aromas to create a pleasant (hopefully!) flavor as it sits on the tongue, even before it is swallowed. A good habit is to allow a wine to sit on your tongue for a second or two before you actually swallow it. If you're at a dinner table, of course, it isn't necessary to do this with every sip. But it's a good idea to do this upon your first taste of a wine, which gives your brain a chance to absorb sensory impressions. It's natural to think about the taste of a wine, the same way you think about the taste of a cheeseburger and fry.

In respect to a wine’s feel on the palate, alcohol gives a wine its “body,” which is a good word to use when describing whether a wine is light, heavy, or somewhere in-between. White wines from Germany (often made from the Riesling grape) and Italian style whites made from Moscato tend to be less than 10% alcohol, and thus are among the lightest wines in the world, and very easy to drink.

California and French white wines made from Chardonnay tend to fall in the 13%, 14% alcohol range, and thus are usually described as full bodied or even heavy. Most varietal whites made from Sauvignon blanc tend to be lighter, around 12% or 13% alcohol, and so are usually medium bodied—neither light nor heavy. Even beginners can quickly learn what their personal preference may be in terms of varietal character or body, and that's the important thing.

Visiting wine influencers tasting Zinfandels in the Lodi Wine Visitor Center.

Red wines such as Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Zinfandel, Syrah and Petite Sirah usually have full alcohol (13%, 14% or more) as well as generous levels of tannin—the latter component, derived from the skins and seeds of grapes with which red wines are fermented—which further accentuate the feel of body.

Although red wines made from grapes such as Pinot noir, Grenache or Cinsaut can be just as high in alcohol as a Cabernet Sauvignon or Zinfandel, they may very well taste lighter or softer in body simply because they are typically lower in tannin, which adds to dryer and sometimes bitter sensory impressions. Therefore, if you prefer red wines that are softer or more "delicate" you may be more of a Pinot Noir, Grenache or Cinsaut lover; but if you love a full bodied red wine with more tannin grip, you may be more of a "Cabernet" person.

#7—Assessments

Finally, you make a quality judgement—another one of your brain's jobs—after processing what your eyes, nose and palate tell you about a wine. You need not be a Master of Wine to make a valid judgement on quality. That is, whether a wine is "good," "great," "so-so" or not-so-good to you. It bears repeating: As in anything—music, books, fashion, cars—everyone needs to decide what is best for themselves. You are your own judge of quality. Not any "expert," not what you may have heard or read, especially not what a sommelier in a restaurant or a salesman in a wine store may try to tell you.

Vineyard tasting of Lodi Zinfandel and Petite Sirah at the back of a truck.

Therefore, you ask yourself: Is the wine you are tasting giving you pleasure? Logic tells you that if you do not like dry, bitter tasting red wines, you may be better off drinking something lighter, sweeter or fruiter, like many white wines. Many consumers used to love White Zinfandel because it's pink, light and usually sweet and fruity. In recent years, however, many consumers have been moving away from White Zinfandel, and gravitating more towards rosés because they tend to be dryer yet are still crisp, light and freshly aromatic in fruit qualities.

If you prefer a white wine that is bone dry, or a red wine that is soft and spicy (i.e., a wine with a scent suggesting black pepper or kitchen spices, like many Zinfandels), then these are the wines you should be seeking out to enjoy. The important thing, going back to our Rule #1 ("there are no rules"), is that you need to cultivate own preferences; and when your remember what those are, you can explore further possibilities in the styles of wine you enjoy the most.

If you have a democratic, or catholic, taste ("catholic' in the sense of appreciating any type or style of wine, as long as it is well crafted), then the qualities you usually end up looking for in a wine usually entail a sense of balance, a harmonious feel, smoothness or "finesse" of different elements in a wine, whether it is dry, sweet, light or full bodied, white or red, pink or bubbly, and no matter what grape or wine region it comes from.

At Lodi's Towne House Restaurant, couple enjoying a multi-wine dinner. Wine & Roses Hotel.

One of the advantages of cultivating a wide-ranging taste, I should add, is that it allows you to better appreciate wines with foods. It is true, no matter what anyone may say, that certain wines go better with certain foods, and vice versa. A Cabernet Sauvignon, for instance, is immensely satisfying with a grilled steak, Zinfandel is amazing with barbecued ribs, and Albariño is totally refreshing with seviche, raw oysters, or seafood salads in a citrusy vinaigrette.

If you can appreciate all kinds of wines, you can probably better enjoy wines in their optimal food contexts. And if you take the word of people in Europe who (after all) were the first to get into wine, wine is a food—or at the very least, something that is best enjoyed with food as a sustenance in and of itself. Thomas Jefferson is often famously quoted as saying, "Wine is a necessity of life" (he drank a lot of wine).

Half the joy of learning how to better appreciate wines is becoming more capable of finding other wines that are equally enjoyable, especially with the foods you love to eat.

If that's been good enough for gazillions of wine lovers all down through the ages, it should be good enough for anyone!

Evening wine tasting at Lodi's Michael David Winery.