Letters from Lodi

An insightful and objective look at viticulture and winemaking from the Lodi

Appellation and the growers and vintners behind these crafts. Told from the

perspective of multi-award winning wine journalist, Randy Caparoso.

What is Lodi terroir? (part 1, Definition)

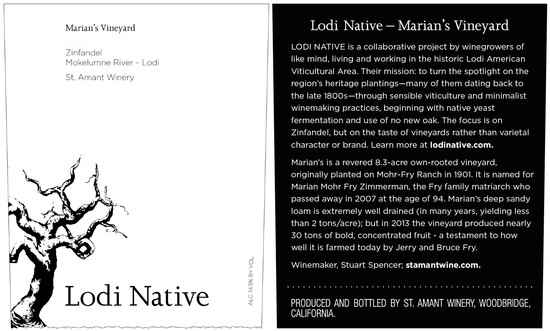

Lodi's Marian's Vineyard, a combination of ultra-deep sandy loam, Mediterranean climate and over 120 years of own-rooted Zinfandel cultivation adding up to a distinctive terroir perceptible in the sensory quality of its wines.

What is terroir?

Out of respect for this concept's French origin, I prefer to italicize the word, although you don't have to, since it's now co-opted into the English language like many other French words (such as élevage, café, chef, sommelier, apéritif, petite, haute couture, de rigueur, et al.).

But be careful how you use it. Merriam-Webster, for instance, simply defines terroir as a "combination of factors including soil, climate, and sunlight that gives wine grapes their distinctive character." That's true, but it's a lot more than that.

Since the French think of vineyard conditions as being one and the same as what ends up in a bottle⏤which is exactly why the finest French wines are sold primarily by their appellation (i.e., place of origin), not the grapes going into the wines or their producers⏤their definition of terroir is multifaceted. Thus, Oxford Languages' definition is threefold:

• The complete natural environment in which a particular wine is produced, including factors such as the soil, topography, and climate.

• The characteristic taste and flavor imparted to a wine by the environment in which it is produced (noun: goût de terroir; plural noun: goût de terroirs).

• Origin, French for "land," from medieval Latin terratorium.

Burgundy, France's Romanée-Conti, a vineyard whose noble history and ecological identity are so distinctive that the vineyard has become synonymous with the concept of "terroir" to wine lovers all over the world.

Still, it is the word terroir, implying earth or terratorium, which often leads to misinterpretation. Terroir is more than about earth, soil, climate, or any other aspect of environment because of the simple fact that vineyards are not wild, extemporous creations of nature, and wines don't make themselves. Everything about winegrowing is also about humanity. People play a large part in all distinctions related to terroir.

During a dinner in 2001, the famous French wine importer Kermit Lynch shared what I thought to be the best and most sensible definition of terroir, which has informed my own grasp of the concept ever since. I am able to quote it because I published an article about that dinner immediately afterwards (see My dinner with Kermit). According to Lynch:

Terroir is a word which many wine writers misinterpret. To the French, the taste of terroir is not "of the soil." Soil is just a small part of terroir. It is also the angle of the sun, the rainfall, the climate, the little breeze that tends to blow in from the next valley, and not in the least, the viticultural and winemaking traditions long associated with that particular region⏤everything that contributes to the character of a wine.

You change the way the wines are grown and vinified, and you change the terroir. That's the problem with most wines of the world and even in France these days. Everyone wants to turn wines into something they are not.

Legendary French wine importer Kermit Lynch. Kyle Johnson.

Because vineyards, like wines, involve human input, viticultural traditions typical of regions or eras can be considered part of a region's or individual vineyard's terroir. Human hands work, well, hand in hand with nature to produce sensory qualities in resulting wines. Hence, the most common definition of terroir is probably the expression "sense of place," which is something perceived on a sensory rather than strictly intellectual level. You experience terroir with your eyes, nose and palate, although you use your intellect to comprehend its nature-related origins.

In respect to human input, you can say that Lodi's historical circumstances, such as the fact that most of Lodi's vineyards are controlled by families who have been farming in the region for as long as 150 years, are very much part of Lodi terroir. It's this unusually long lineage that also gave rise to the region's industry leading sustainable movement, manifested in the now widely duplicated LODI RULES for Sustainable Winegrowing. Simply put, if it wasn't for these enduring ties to the land and community, growers would not have been willing to come together to put forth this humongous, continuously evolving effort.

Then there is the consciousness influencing the recent evolution of smaller production wines: For one example, the impact of vintners who formed a group called Lodi Native in 2012, dedicated to the production of low intervention vineyard-designate Zinfandels meant to taste like where they come from, not like "Zinfandel."

To repeat: Zinfandels that are not supposed to taste like standard conceptions of Zinfandel; but rather, the singularly unique vineyards from which they originate. While produced by only nine vintners, these wines have since influenced the way many other Lodi wines are grown and produced today. All part of the modern day evolution of Lodi terroir.

Michael and David Phillips, owners of Lodi's Michael David Winery, whose family lineage as Lodi farmers since the late 1860s played a key part in the formation and successful roll-out of the industry leading LODI RULES for Sustainable Winegrowing, hence Lodi terroir. John Curley Photography.

Absolutely, positively, it is very possible for "sense of place" to be completely obscured in wines, especially because of the way the vast majority of domestically grown commercial wines⏤and most of the New World, for that matter⏤are produced, marketed and sold: With priority placed on qualities such as varietal character or brand identity, with little or zero regard for terroir.

Although sensory qualities reflecting where wines are grown is not a priority in most commercial wines, there is nothing wrong with that. We're American, not French, we do things our way. As long as the American wine industry perceives this as the way most Americans buy or appreciate wines, this is how American wines will be made.

However, even the domestic wine industry is changing, slowly but surely. Whereas 50 or 60 years ago, handcraft producers in American settled on the idea of producing wines that express varietal qualities and brands as best as possible, more and more small, artisanal, handcraft producers are now endeavoring to produce wines with a stronger "sense of place."

They want, siimply put, a Napa Valley Cabernet Sauvignon to taste like it could only come from Napa Valley and nowhere else. The same for Sonoma Coast Chardonnay, Paso Robles Syrah, Willamette Valley Pinot Noir or Finger Lakes Riesling. For many American producers, capturing a distinct "sense of place" is becoming increasingly important.

Tegan Passalacqua, whose work as a minimal intervention winemaker for Turley Wine Cellars and his own Sandlands brand has helped define the sensory qualities and prestige of individual Lodi vineyard terroirs. John Curley Photography.

The driving force behind this movement away from branding or varietal character is undoubtedly economical: In the U.S. alone there are close to 12,000 bonded wineries competing in an industry adding up to approximately $276 billion in overall economic impact. In such a crowded field, wine producers have to find ways of differentiating themselves. What better way than producing wines that taste like where they come from? Instead of being, say, just another "Cabernet Sauvignon" or "Chardonnay." Logic tells you that if this approach has worked for, say, the French, it can certainly work for Americans.

Terroir, in other words, is becoming a name-of-the-game.

Terroir in terms of sensory distinctions (and the recent movement towards "natural")

Exactly how does the sensory perception of terroir work? Let's discuss⏤by way of Lodi's signature grape and wine, Zinfandel.

In wines with "sense of place," terroir-related distinctions are expressed through aromatic and structural profiles of wines. Lodi-grown Zinfandels, for instance, are known for their fragrant, red fruit qualities, typically suggesting cherry, often with black tea-like nuances, whereas Zinfandels grown in heritage vineyards in Sonoma County or Napa Valley have less floral profiles yet are often more deeply aromatic, often suggesting darker fruits like blackberry or plum mixed with red berries.

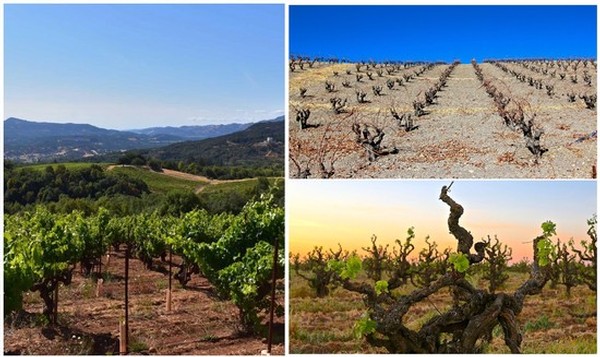

Three distinct old vine Zinfandel terroirs producting distinctive wines unique to each place: (from left) the rocky clay hillsides of Monte Rosso in Moon Mountain/Sonoma Valley, the steep calcareous vineyard of Ueberroth Vineyard in Willow Creek-Paso Robles, and the flat, sandy site of Steacy Ranch on the east side of Lodi's Mokelumne River.

Lodi Zinfandels are also generally softer in tannin, and Sonoma and Napa Zinfandels are firmer and grippier in the phenolic content derived from grape skins, seeds and (when wines are fermented as fully intact "whole clusters") stems. These distinctions are the direct result of the differences in the regions' physical terroir. North Coast Zinfandels are typically grown in shallower, rockier, often hillside soils in addition to climates with more pronounced diurnal temperature swings; as opposed Lodi Zinfandels grown in extremely deep, sandy soils on flat terrain, in a slightly warmer climate with slightly more moderate diurnal swings.

You can drill down further by comparing terroir-related characteristics of Zinfandels grown on the west side vs. the east side of the City of Lodi. West-side Lodi Zinfandels are typically earthier, tinged by notes suggesting some kind of loaminess, whereas east-side Lodi Zinfandels tend to be more floral and red fruit-focused, with almost no earth tones.

Old-time Lodi grape growers and vintners have always known the differences between east and west side Zinfandels. In the past, most Lodi Zinfandels all ended up in gigantic vats to produce "jug" wines or value-priced varietal wines, no matter where they're grown. Even in the rare instances when vineyards were bottled separately, old-timers never used the word terroir (they're not French!) to describe a Lodi Zinfandel's "sense of place," but terroir was always exactly what it was.

Monte Rio Cellars owner/winemaker Patrick Cappiello with assistant winemaker Jesus Aleman, popular proponents of minimal intervention winemaking endeavoring to produce wines as true to Lodi terroirs as possible.

Today, more than a few local wineries openly espouse terroir driven qualities by producing wines in a fashion often described as "minimum intervention." Typically, with use of native yeast for fermentation; no use of enzymes to enhance color or increase extract, no acidulation or wood amendments, and generally speaking, preference for aging in older "neutral" barrels to emphasize natural fruit and keep "oak" character from hiding terroir-related subtleties. Many consumers, in their enthusiasm for less predictable commercial styles, now also describe this as "natural" style winemaking.

Low intervention winemaking, of course, is not exactly "natural" because they are not spontaneous acts of nature, which is why many proponents of more commercial styles of wine object to the use of the word natural. A big criticism is that there is no precise definition of "natural," officially or unofficially. Natural wine enthusiasts, of course, don't give a darn. As long as a wine is made with as little artifice as possible, and better expresses where it comes from, they are happy to use the word as a category or description in complete disregard of naysayers.

Oversized "neutral" ovals utilized by Haarmeyer Wine Cellars every year to highlight natural fruit qualities of wines without the obfuscation of strong oak flavors.

Case in point, the recent proliferation of "natural wine bars" all across the country. As in all things, the consumer is always "right." If they want a bar or store that specializes in so-called natural wines, that's what they're going to get. Later on, down the road, if consumers get tired of that concept, those stores and bars will either change or go out of business. Maybe they will, maybe they won't.

The second big criticism of natural as a wine term is the opinion that most natural wines are not very good. Because they don't follow accepted protocols, they can be unpredictable, unstable, often "dirty" tasting. It is true, many of them are. Many of them, however, are also among the finest wines in the world, which is exactly why there are more minimum intervention style producers than ever. In their desire to produce "great" wine, many of them are going natural, dispensing with most of the machinations typifying commercial styles.

In terms of business, it's also called (again) differentiation. In order to define yourself as a unique brand or producer, you have to find ways to make your wines different. This is not rocket science. In a sense, it's something of a natural movement.

Or, you can say, a matter of capturing terroir!

Our next Lodi Wine post: What is Lodi terroir? (Part 2: Mediterranean Climate)

Ser Winery owner/winemaker Nicole Walsh, one of many small, handcraft producers now working with Lodi fruit, implementing native yeasts, neutral puncheons (i.e., double-sized barrels) and minimal sulfuring, yet produces perfectly clean, fresh vividly terroir focused wines such as Becthold Vineyard Cinsaut (from vines planted in 1886!).