Continued from The Mokelumne River Viticultural Area (part 1)

From sandy loams to loamy sands

When Lodi winemakers extol the qualities of Mokelumne River AVA grown grapes and wines, almost universally they talk mostly about soil. It is topography and soil that distinguishes Mokelumne River from the six other sub-appellations of Lodi, and it is the variations of a single soil type – from sandy loams to loamy sands – that distinguish some parts of Mokelumne River from other parts of Mokelumne River.

In the original 2005 petition submitted to the TTB for seven new American Viticultural Areas within the Lodi AVA, it is explained: “Sandy loam Tokay and Acampo soils dominate the proposed Mokelumne River viticultural area. The soils are young, deep, and drain well… Also, the soils tend to be granular and crumbly, of a fine texture and without gravel… with low moisture holding capacity.”

In fact, few AVAs are defined by as much of a consistency of topography (10 to 85-ft. elevation flats, with less than 2% slopes) and singular sandy alluvium as the Mokelumne River AVA. Whereas most American wine regions consist of a multiplicity of soils, slopes and elevations, in the Mokelumne River AVA there are no steep mountains or significant hills, no boulders, rocks or even gravel: just this well drained mix of decomposed granite (i.e. DG, derived from the base rock of the Sierra Nevada, eroded away by constant river action) and sediment washed down from the mountains and into San Joaquin Valley and the Delta over the past 25,000 years.

Hence, when the mid-nineteenth century settlers finally arrived in the Mokelumne River area, they found a lush prairie environment of grasslands and valley oaks (Quercus lobata) and blue oaks (Quercus douglasii), with herds of elk and antelope, grizzly bears still roaming freely, and rivers teeming with salmon and other fish.

According to Ralph A. Clark (Lodi – Images of America), grapes were also part of the original landscape; albeit native varieties, “growing wild dangling from the trees along the riverbanks.” The Calaveras River (a Spanish name, meaning “skulls,” given by explorer Gabriel Moraga in 1806) forming the south-east boundary of the present-day AVA was originally called Wine Creek by early trappers, due to the abundance of wild vines – something you can still see today even along the greatly diminished waterway, climbing over trees and bushes.

The sandy component of the Mokelumne River area’s Tokay and Acampo soil series allow for ideal drainage, vine health, and naturally moderated grape yields. Since sand is one of the few mediums in which the root louse phylloxera is unable to proliferate, there are several thousand acres of ungrafted, healthy old vine plantings in the Mokelumne River appellation (primarily Zinfandel and Carignan, with some Grenache, Alicante Bouschet and Cinsaut, planted anywhere between 1886 and 1965), still thriving on their own rootstocks.

Below the surface of the Mokelumne River plain is an enormous aquifer of water, which made the farming of a succession of major crops in this porous yet fertile sandy loam that much easier. The first nineteenth century settlers successfully grew barley as well as one of the largest wheat crops in the world. When wheat prices fell, the Mokelumne River area’s high water table allowed for a flourishing watermelon industry – in fact, between the late 1880s and 1900 Northern San Joaquin Valley held the title of “Watermelon Capital of the World.” Today, wine grapes (table and raisin grapes are no longer commercially cropped in Mokelumne River) compete with almonds, walnuts, and cherries as the region’s major agricultural products.

Prior to construction of obstructions such as the Pardee Dam (1929) and Camanche Dam (1963) for the purpose of flood control and irrigation diversion, a high water table made dry farming in the region’s permeable alluvium a practicality in the Mokelumne River area. Today, with water tables at depths of 50-60 feet or more, Mokelumne River viticulture is dependent upon irrigation. While furrow irrigation is still practiced, deficit irrigation (i.e. DI) has become more common through drip irrigation systems; leading to vigorous vine growth, and ideal balance of leaf canopy and fruit for either high production grape growing (still predominant in the region) or the increasing demand for lower production premium quality winegrowing.

Winemakers talk dirty and triangles

How can soil composition possibly have an effect on grape quality and, ultimately, the sensory qualities in wines? It has been observed that Mokelumne River soils in vineyards located on the east side of the City of Lodi are different from soils found on the west side in two ways:

1. More sand content – increasing drainage (i.e. less moisture retaining capacity) – along with less loamy organic material.

2. Lower water tables.

The most direct impact of lower water tables and sandier soil is on average cluster weight and berry size in east side grapes. Smaller berries and clusters mean higher skin to juice ratios as well as earlier ripening; and both factors can result in lower pH, higher total acidity as well as increased phenolic content (the color, tannin as well as aromatic compounds of wines are derived from grape phenols and polyphenols). In plainer English, this means brighter, crisply balanced white wines, and darker, firmer, zestier, flavorful red wines. The opposite – larger clusters and berries – means lighter colored, softer, rounder, less aggressively flavored wines.

This, of course, does not preclude the effects of temperature, rainfall, solar exposure, clone or rootstock selection, disease pressure, vineyard practices (vine training or trellising, pruning, irrigation, cover cropping, pest management, composting, etc.), picking decisions, and myriad other factors applicable to any given vineyard site or region. But in the Mokelumne River AVA, it is still the region’s sandy soil composition (along with Mediterranean climate) that exerts an overriding influence on grape and wine qualities.

That said, when we asked several viticulturists and winemakers to comment on the benefits of farming in the Mokelumne River Viticultural Area we were not surprised that their observations focused mostly on the variations of sandy loam and loamy sand found throughout the appellation.

First, Franck Lambert – a French schooled winemaker who currently consults for Lodi’s Watts Family Winery and Stama Winery – tells us that, as in the regions of France, Mokelumne River exhibits its own unique terroir, which he defines as “an association of soil + climate + plant material + know-how.” In reference to the know-how part – that is, the input of growers – Lambert believes that the major controllable still comes down to water. In fact, contends Lambert, “terroir is a matter of water… when we look at the flow of components going through the plant from bud break to fall, it becomes obvious that water is the main variable. Water regulates production in terms of quantity as well as quality.”

Comparison of Zinfandel clusters grown in two different Mokelumne River AVA vineyards: a larger berried Mohr-Fry Ranches cluster (left), and a smaller Maley’s Wegat Vineyard cluster (right)

Paul Verdegaal, who is Cooperative Extension San Joaquin County Farm Advisor for University of California’s UC Integrated Viticulture program, reminds us that the “Mokelumne River AVA encompasses much of Lodi’s traditional production area, first established with Flame Tokay vines around 1864.”

Jonathan Wetmore – whose Round Valley Ranches manages over 2,000 acres in Lodi, primarily in the Mokelumne River AVA – has spoken to us about the historic symbiotic relationship between Tokay and Zinfandel that has existed since the 1860s. “The interesting thing about Zinfandel and Tokay,” says Wetmore, “is that both grapes thrive in the region’s deep, rich, fine sandy loams. Old timers always knew that wherever you could get the Tokay to turn its bright pink color, you could also grow the highest quality Zinfandel.”

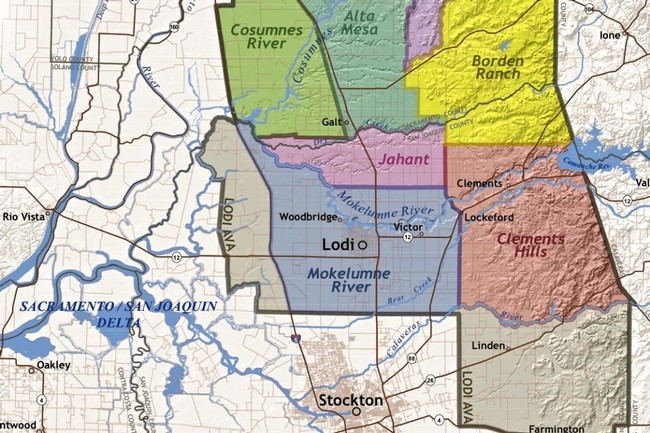

However, according to Wetmore, Tokay was even more site-specific than Zinfandel. “Lodi was the king of Tokay, because you couldn’t grow it elsewhere in California – you needed the moderating, cooling breezes from off the Delta to grow it – but soil was just as important. You can drive down Peltier Rd., where on one side you have the fine sandy loam of Mokelumne River, and on the other side, the coarser sandy clay loam of the Jahant AVA. Old timers could never get Tokay to consistently turn color and ripen in Jahant soils.”

In 2008 Sue Tipton, the owner/grower of Acquiesce Winery, planted a block of Rhône Valley grapes (Viognier, Roussanne, Grenache Blanc, Piquepoul and Grenache) along Peltier Rd., right at the dividing line between the Jahant and Mokelumne River Viticultural Areas. Tipton talks about her experience: “Our 18-acre property was historically river bottom, before the succession of dams were built along the Mokelumne River. Consequently, approximately 80% of our soil is a fine sandy loam; but as the vineyard approaches Peltier to the north, we see more clay soils. The sandy loam gives a great fruit intensity, but we’ve had issues with our Roussanne planted closer to Peltier. Roussanne is notoriously tricky to grow anyway, here as well as in France, but we lost 250 of the plants. We have since replanted on more aggressive rootstocks that we think will be more suitable to clay soils.”

Verdegaal talks further about the variabilities in Mokelumne River soil; saying, “The deep, well-drained soils that dominate the AVA are mostly fine sandy loams, but the alluvial flows of the Mokelumne have also created fingers of more coarse textured loamy sands, fine sands, and loamier soils.” A major factor, adds Verdegaal, is that these soils provide “growing conditions for vine balance and quality fruit with minimal inputs” – one of the reasons why Lodi was the first viticultural area in the U.S. to formalize third party certified sustainable practices, called Lodi Rules for Sustainable Winegrowing.

Craig Rous – owner/grower of Rous Vineyard (one of Mokelumne River’s most venerated Zinfandel growths) as well as Director of Operations at Lodi’s Bear Creek Winery – breaks down the benefits of sandy Mokelumne River soils as such:

• Reduces vine vigor and crop size

• Promotes deep roots

• Enhances fruit concentration

• Encourages deeper color

• Gives typically lower pHs (i.e. higher natural grape acidity)

• Results in earlier harvest dates (thus, less danger from late season disease pressure)

In addition, Rous cites the existence of deeper, sandier soils on the east side of the City of Lodi in an area he calls the “Victor Triangle.” According, to Rous, the “triangle” points are located approximately at Bruella Rd. at Orchard Rd. at the north, Curry Rd. and E. Kettleman Ln. to the west, N. Locust Tree Rd. and E. Kettleman Ln. to the east. Says Rous, “There seems to be a lot of really good blocks within this area that typify the AVA for me.”

Rous elaborates: “Soils within the ‘triangle’ have even more sand than the rest of the AVA. If you look at a soils map, they are described as loamy sand rather than sandy loam (the first word is the minor component, the second word the major component). While I am not entirely comfortable saying all vineyards in the Mokelume River AVA or even the ‘triangle’ fit these descriptions, I think the wines from the Victor area, especially Zinfandels, tend to be more elegant, better balanced, with less ‘fruit bomb’ character, especially when harvested at optimal balance.”

Besides Rous Vineyard’s Zinfandel (planted in 1909; bottled by Macchia Wines and Ironstone Vineyards), other notable plantings falling within the triangular coordinates proffered by Rous include: Harney Lane Winery’s Lizzy James Vineyard (Zinfandel planted in 1901); Rauser Vineyard (Carignan dating back to 1906); Mokelumne Glen Vineyards (German and Austrian grapes); some of Mettler Family Vineyards‘ best Cabernet Sauvignon, Petite Sirah and Zinfandel blocks off Alpine Rd.; as well as the Las Cerezas Vineyard (planted to Spanish grapes), Tegan Passalacqua's Kirschenmann Vineyard, Schmiedt Ranch and McCay Cellars' Lot 13 Vineyard (the latter three, Zinfandel plantings dating back to 1915/1916)..

Markus Bokisch has gone so far as to speak of the possibility of one day proposing still another sub-AVA within the Mokelumne River AVA, encompassing this pocket of deep, beach-like sand found around the tiny CDP of Victor (population 293), east of Lodi between Hwy. 99 and Hwy. 88. Bokisch refers to the “more nuanced, softer perfume” of Zinfandels from this sub-area; and Turley Wine Cellars’ Tegan Passalacqua (owner/grower of Kirschenmann Vineyard) has described these Zinfandels as “prettier, higher toned wines, not inky dark or massive, with medium to medium-plus concentration, and aromatics that are more on the floral side, yet with a good amount of spice, pepper and just enough tannin structure to make it full, but not gigantic.”

Heritage Oak Winery’s Tom Hoffman – who farms younger, trellised Zinfandel (planted in the mid 1990s) within what would be the north point of Rous’ triangle – tells us, “Craig’s points that apply to me would be...

• Reduced vigor – I’m always frustrated with the output of my vines, which never seems to be as much as other growers, to the point where I’ve wondered if I’m doing things wrong;

• Deep roots – I know my roots are deep because I can irrigate deeply and then dry-farm during the production season… you can’t do that if you have shallow roots because they run out of water and the vine dries up.”

Chad Joseph – the consulting winemaker for a half-dozen Lodi wineries (including Harney Lane Winery, Oak Farm Vineyards, and Maley Brothers) – has the experience of producing wine from all parts of the Mokelumne River AVA. He acknowledges that “there are ‘fingers’ of very fine sandy soils, with less loam, in this appellation, like the soil type found in Lizzy James Vineyard… these vines are some of the earliest to ripen, with less vigor and more concentration, compared to other old vine vineyards in the Lodi AVA.”

Joseph contrasts the loamy sands on the east side with the sandy loam found in the highly regarded Wegat Vineyard on the west side (between Interstate 5 and the City of Lodi), owned by the Maley family, who have been farming in the area for some 150 years. Says Joseph, “Wegat Vineyard has slightly loamier soil than Lizzy James on the east side. Like Lizzy James, Wegat ripens earlier than most, and is very concentrated with small berries. But unlike Lizzy James, Wegat tends to have more loamy and herbal characteristics that I find very unique and pleasing. In general, though, I find that the best Mokelumne River vineyards all have potential for better concentration, less vigor, and higher acid due to the earlier ripening patterns.”

107-year old own-rooted Carignan in the Jessie’s Grove estate on the west side of the Mokelumne River AVA

Other west side Mokelumne River AVA Zinfandels of note include Soucie Vineyard (planted in 1916, going to m2 Wines and Michael David Winery); TruLux Vineyard (McCay Cellars); The Lucas Winery‘s ZinStar Vineyard; and the newly emerging Stellina and Mikami estate vineyards. As a group, all of these Zinfandels tend to achieve round, floral qualities; more often than not with underlying earthy, loamy, organic qualities (a complexity less common in east side Mokelumne River Zinfandels).

Mark Chandler, the former Executive Director of Lodi Winegrape Commission, talked to us about the ever-present environmental influence of the Mokelumne River itself: “I have two Cabernet Sauvignon vineyards in the Mokelumne River AVA, on the benches on either side of the river, about 7 miles apart from each other. Despite this distance the soils are remarkably similar – fine, deep, sandy, and moderately fertile. The vine roots easily penetrate into the soil, and irrigation is spoon-fed when called for. Due to the river’s moderating influence, afternoon highs are a few degrees cooler than in adjacent appellations. Consequently the wines are robust, fruit-forward, but a bit soft, requiring a little oak for structure. They are silky and smooth rather than big and powerful.”

Michael Klouda monitors vineyards throughout the Lodi AVA as a viticulturist for Phillips Farms (Michael David Winery’s farming arm). Says Klouda, “I believe even within the Mokelumne River AVA there are still plenty of different micro-climates to be found. In the eastern section of the AVA there are spots where the soil is so sandy that it almost feels like being on a beach. These sandy soils seem to heat up the vineyard enough to increase grape maturation by at least a few weeks –some of the first Zinfandels to be picked come from this area.”

For his own MK/Michael Klouda Wines label, however, Klouda produces old vine Zinfandel from Schulenburg Vineyard, located on the west side of the Mokelumne River AVA between Sargent Rd. and W. Kettleman Ln. Says Klouda, “The fruit from Schulenburg seems to have its own unique ‘baker’s spice,’ different from other vineyards. In contrast, the 1.5-acre vineyard down the road farmed by Myron Liebelt makes a huge, dark fruit flavored wine. There seems to be plenty of vineyards in the Mokelumne River AVA just waiting to be expressed, and appreciated, as single vineyard wines.”

Our next blogpost: The Mokelumne River Viticultural Area (part 3) – Grapes, ungrafted vines, rags to riches